She wanted to be a mom. So she chose a cancer treatment that gave her a chance

Even as a child, Maggie Loucks believed being a mom was her destiny.

“It was always inherently who I was,” says Loucks, of her tendency to take care of others. “Friends always turned to me and would always joke that I was the mom of the group.”

So when Loucks got a breast cancer diagnosis at age 28, her thoughts immediately ran to the kids she’d always wanted.

“After the initial shock of the diagnosis, that was the most present thing on my mind,” says Loucks, who was a newly married nursing student in Boston at the time.

The thought of not having her own biological children with her husband gutted her.

“And that was really almost harder than the treatment for breast cancer,” she says.

The type of cancer Loucks had, known as HER2-positive, is increasing at alarming rates among young women. This cancer is sensitive to hormones, and tends to spread quickly. Loucks was told that in the past, treatments had to match the cancer in harshness, and the toxins damaged ovaries and other organs in the process.

Loucks, who became an oncology nurse practitioner, refers to this as the “kitchen sink” approach: “You throw the kitchen sink at them; you give them every type of chemotherapy because you do not want this coming back.”

Less collateral damage

But treatments are rapidly changing. Medical breakthroughs, and genetics in particular, are enabling new drugs to better target specific subtypes of cancers, which not only dramatically increases chances of survival, it spares the body a lot of collateral damage. That, in turn, means some patients can choose how to address their cancer in ways that take into account their emotional and physical quality of life, after treatment.

Medicines that improve the quality of life in survivorship are the new frontier in treating cancer, says Dr. Ann Partridge, acting chair of oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Maggie Loucks’s oncologist.

“We need to do more to improve those psychosocial outcomes and not only survive their cancer, but thrive after,” she says.

For nearly half of Partridge’s young adult patients, that includes trying to preserve fertility. Her research shows many women could treat their breast cancer for roughly two years — then pause to get pregnant — and resume treatment after giving birth without additional risk of cancer recurrence.

“Not only was that feasible and the vast majority of women were able to get pregnant and have a live birth, but it also appeared safe,” she says.

Partridge offered Loucks another alternative — a chemotherapy regimen that’s less aggressive in killing cancer cells and does less damage to ovaries, potentially preserving fertility. Loucks chose that route and harvested her eggs before treatment for good measure.

“I went into my chemotherapy with 15 embryos and I was so excited – elated,” she says.

Still, a fertility struggle

After five and a half years of treatment, Loucks and her husband finally began transferring their frozen embryos. One by one, they perished or failed to implant. Several times Loucks miscarried. Meanwhile, her friends were having babies, and she began to despair: “I was utterly devastated. So traumatizing. It was years and years of heartache and sadness.”

Because her ovaries remained healthy, Loucks was able to harvest more eggs. After two years of in-vitro fertilization, Loucks gave birth to twin daughters, Sloane and Everly. Two years after that, she conceived another girl, Kingsley, naturally.

“I don’t know if I would’ve gotten the same result, if I’d gotten the other chemotherapy,” says Loucks, now 40 and living in London with her family. She remains cancer free, and worries less about recurrence as time goes on.

Yet occasionally she wonders about her choice to take the less aggressive chemotherapy: “Am I going to regret this? What if my cancer comes back and I made the wrong choice? Now that I have kids, I have a different kind of fear. I want to be around for as long as possible.”

Gratitude and perspective

But not a day goes by that she doesn’t appreciate her past struggle, she says. She put her experiences to good use professionally when she worked with her former doctor, Ann Partridge, helping other women deal with fertility through cancer. And it has had a profound effect emotionally.

“Understanding and realizing how precious life can be is one beautiful thing from my cancer diagnosis that I’ve tried to hold onto,” says Loucks.

Katie Hayes Luke edited the visuals for this story.

Trump has rolled out many of the Project 2025 policies he once claimed ignorance about

Some of the 2025 policies that have been implemented include cracking down on immigration and dismantling the Department of Education.

The 2026 Olympics are the most widespread in history. See what’s happening where

Competitions will be hosted at 25 venues spanning an area of more than 8,000 square miles. Here's what's happening at each of the four main clusters.

U.S. lawmakers wrap reassurance tour in Denmark as tensions around Greenland grow

A bipartisan congressional delegation traveled to Denmark to try to deescalate rising tensions. Just as they were finishing, President Trump announced new tariffs on the country until it agrees to his plan of acquiring Greenland.

Can exercise and anti-inflammatories fend off aging? A study aims to find out

New research is underway to test whether a combination of high-intensity interval training and generic medicines can slow down aging and fend off age-related diseases. Here's how it might work.

High-speed trains collide after one derails in southern Spain, killing at least 21

The crash happened in Spain's Andalusia province. Officials fear the death toll may rise.

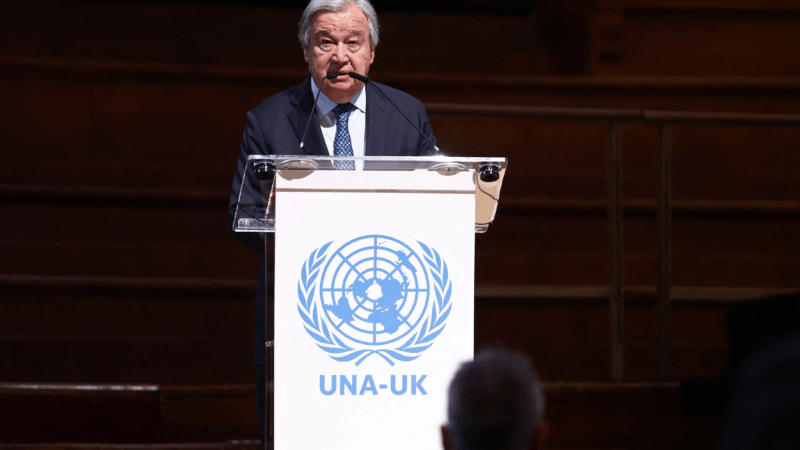

United Nations leaders bemoan global turmoil as the General Assembly turns 80

On Saturday, the UNGA celebrated its 80th birthday in London. Speakers including U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres addressed global uncertainty during the second term of President Trump.