Photos: How torn pictures and trusted herbs create healing in Colombia

Stitching sutures is one way doctors treat wounds.

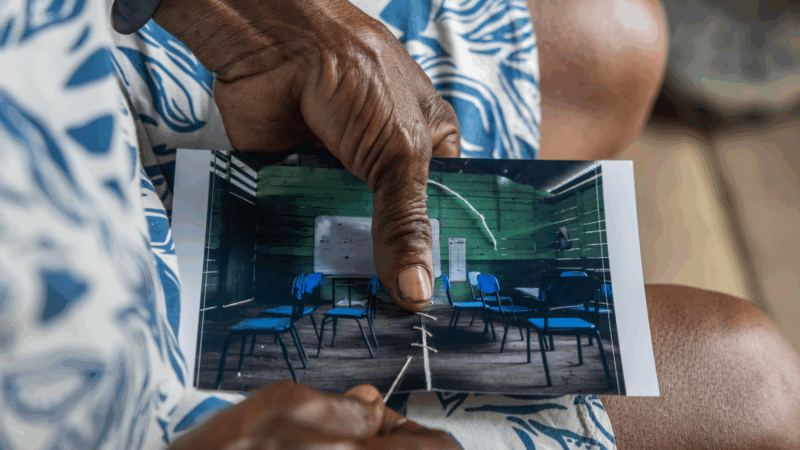

But now there’s another kind of stitching to heal psychic wounds: tearing up and then sewing back together photographs of loved ones and homes. That’s one of the rituals devised in the remote area of Alto Baudó in the western region of Colombia, where feuds between armed rebel and criminal groups have terrorized the population for years.

The photo stitching is part of a two-year project conceived of by Doctors Without Borders, working with community healers and midwives from 2022 to 2024. The goal has been to create rituals to help manage the anxiety, depression and other mental health risks posed by the area’s widespread violence.

The rending and mending of photos is a metaphor for healing, according to Colombian photographer Fernanda Pineda, who documented the project. Other rituals to reclaim memories of once peaceful places beset by violence include the use of fragrant herbs and leaves the healers traditionally employ to reduce pain and bring comfort.

The organization also brought in medical teams to train 48 people in the community as health workers and health promoters to ensure the availability of basic medical services. That’s essential because the isolated location means that it may take two to three days to reach a health center or hospital.

As Santiago Valenzuela, a communication manager for Doctors Without Borders from Colombia, said, “We created a dialogue between Western medicine and local healers.”

Seven healers and the rituals they conceived and used during the course of the project are chronicled in Pineda’s photography series, Riografias del Baudó. It’s on view at the annual Photoville Festival in Brooklyn, New York, where a sprawling array of shipping containers are converted into mini-photo galleries through June 22. The project’s title uses the Spanish word for river in a play on the Spanish word for photograph, fotografía.

“We chose to include Riografías: Women Healers of Alto Baudó because [the exhibit] exemplifies the power of visual storytelling to illuminate overlooked global health crises and the extraordinary resilience of women,” says Photoville creative director and co-founder Sam Barzilay, noting that the project depicts women as “agents of change, resilience and healing in the face of systemic neglect — stories we felt urgently needed to be seen and acknowledged.”

About 14,000 people, many of them of African descent or indigenous Embera, live in the approximately 130 communities in this rainforest area bordered by the Baudò River, Pineda said. Thousands of people have fled the region to avoid confrontations between armed groups that sometimes forcibly try to recruit them. The use of land mines by the combatants poses a constant danger. As a result of these threats, many of those who remain confine themselves for safety, unable to work or attend school.

People of all ages gather at the river in the above photograph, with family bungalow houses and immense greenery receding into the distance. “This shows their community,” Pineda says. “It’s morning, you see intimate moments with one woman holding a baby, people doing their wash, everyone is there.”

The kids at the river play with pails and balls and, as in this photo, a small canoe seen from the back. This young boy may have painted his face as a symbol of protection, Pineda said.

The peaceful river scene belies the stress that the community has suffered. “Chachajo is sick with fears. I am sure of that, because I, myself, live with that sickness,” says traditional healer Carmen Fidela Mena,

She has learned medical techniques as well. “Many years ago, a physician from Doctors Without Borders taught me how to suture wounds,” Mena says. “Sometimes, I don’t have the tools, like the needles and thread, so I have to use what I have: black thread and a well-disinfected sewing needle. And when there´s no sewing thread, we´ve had to use dental floss.”

This photo is overlain with dried, preserved leaves. Healer Teolinda Castro, from the community of Mojaudó, is quoted as saying: “At the Mojaudó school, there was a confrontation that left bullet holes in the walls and ceiling. The resucito plant is used to cure pain. If my child tells me ‘Oh, mom, my head hurts,’ I get some resucito and wash their little head with it. The day [the confrontation at the] school happened, I got under the bed because I thought: ‘Am I going to die? If my blood pressure rises, I die here.’ So I stayed still.”

These new rituals do bring a sense of hope, the healers say — even as the fighting continues.

Diane Cole writes for many publications, including The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. She is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges. Her website is DianeJoyceCole.com

How George Wallace and Bull Connor set the stage for Alabama’s sky-high electric rates

After his notorious stand in the schoolhouse door, Wallace needed a new target. He found it in Alabama Power.

FIFA president defends World Cup ticket prices, saying demand is hitting records

The FIFA President addressed outrage over ticket prices for the World Cup by pointing to record demand and reiterating that most of the proceeds will help support soccer around the world.

From chess to a medical mystery: Great global reads from 2025 you may have missed

We published hundreds of stories on global health and development each year. Some are ... alas ... a bit underappreciated by readers. We've asked our staff for their favorite overlooked posts of 2025.

The U.S. offers Ukraine a 15-year security guarantee for now, Zelenskyy says

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said Monday the United States is offering his country security guarantees for a period of 15 years as part of a proposed peace plan.

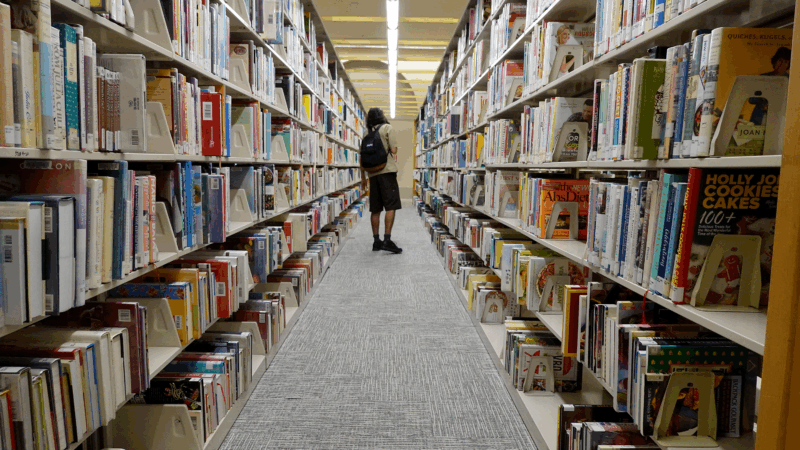

Genre fiction and female authors top U.S. libraries’ most-borrowed lists in 2025

All of the top 10 books borrowed through the public library app Libby were written by women. And Kristin Hannah's The Women was the top checkout in many library systems around the country.

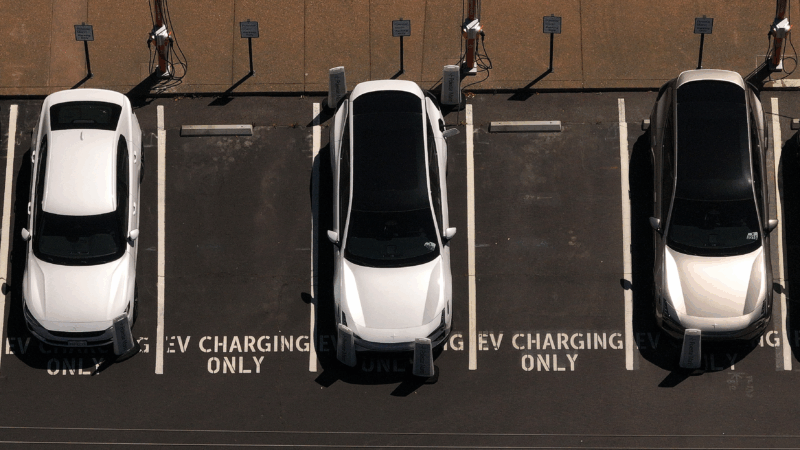

Electric vehicles had a bumpy road in 2025 — and one pleasant surprise

A suite of pro-EV federal policies have been reversed. Well-known vehicles have been discontinued. Sales plummeted. But interest is holding steady.