Patients scramble as cheaper obesity drug alternatives disappear

When Christina and Jackson Agar used to get a pizza, they’d polish it off the same night. Things are different now that they’re both taking an obesity drug.

“We recently ordered a pizza and we ate some of it the first night and then the next day we had maybe a little bit more,” says Christina. “And then we ended up throwing the pizza away because it had gone past the days that you could eat it. And it was so strange because we have never done that.”

“No, never,” her husband, Jackson, says.

They’ve each lost about 20 pounds in six weeks. But the Agars, who live in Minnesota, aren’t taking Eli Lilly’s Zepbound; their insurance doesn’t cover it.

They’re taking a cheaper alternative that contains the active ingredient called tirzepatide.

It’s made by a compounding pharmacy, which is a special kind of pharmacy that’s allowed to essentially make copies of drugs during shortages.

Since starting on the compounded tirzepatide, Christina says she has more energy for their four kids. And Jackson doesn’t need his sleep apnea machine anymore. (In December, the Food and Drug Administration approved Zepbound to treat sleep apnea.)

“It is completely life-changing to take a bite of these triggering foods and just be like, enjoy it, say, ‘Yup, that was good and now I’m full,’ ” he says.

But the compounded drugs the Agars and others have come to rely on aren’t here to stay.

The FDA says compounding pharmacies have to stop making tirzepatide because the agency declared the yearlong Zepbound shortage over. The deadline is Wednesday.

How patients are feeling

The Agars are worried. Other patients are sad. Some are just angry.

In Arizona, Margot Carmichael was in denial.

“I thought what I think a lot of people perhaps did: Oh, it’ll be fine. These compounding and telehealth places are making millions off of this and helping so many people. There’s no way this is going to stop being available, ” she says.

It’s been confusing for patients. Some telehealth companies have been telling them they won’t be affected. Others have been offering last-minute sales as the FDA deadline nears.

“So March 19, we are essentially done,” says Josh Fritzler, the chief financial officer for Olympia Pharmaceuticals, which has a large compounding pharmacy in Orlando, Fla., called an outsourcing facility. Production will stop, but pharmacies can still dispense Olympia’s tirzepatide until it runs out or expires.

Olympia has made the medicine for more than 100,000 patients a month, Fitzler says.

“They’re nervous, they’re scared,” he says. “And we’re just hopeful that we can make enough in the time being to fill patients’ ‘scripts.”

There are seven large facilities, including Olympia’s, making tirzepatide, according to the FDA’s latest Outsourcing Facility Product Report. They are required to follow the same safety and quality standards as brand and generic drugmakers and are inspected by the FDA. Smaller compounding pharmacies, which are regulated by states, were supposed to stop in February.

Consumers get creative

Many patients told NPR they have been stocking up on compounded tirzepatide.

Carmichael doesn’t have health insurance right now. She says she can only afford a small stockpile.

“I don’t have the money,” she says. “So I’m going to borrow the money and try to get three more months and stretch it out as long as I can and hope that six to nine months from now, there’ll be another solution.”

Eli Lilly sells Zepbound vials at a discount for people not using insurance, but Carmichael says they’re still too expensive. She would have to pay $500 or $600 dollars for a month’s supply of her dose from Lilly.

For around the same price, she has been able to get three months’ worth from a compounding pharmacy. The standard forms of Zepbound, which come in an auto-injector pen, can cost more than $1,000 per month without insurance.

Carmichael and other patients NPR spoke with say they buy large vials and then stretch the medicine out over an extended period of time (until the vials expire) to save money.

But the Eli Lilly vials don’t contain a preservative and are labeled for single-use, which the patients say complicates their cost-saving strategy. Also, to keep the company’s discount, patients like Carmichael would have to renew their orders every 45 days. “They’re making it as difficult as possible for people,” she says.

The drugmaker didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment, but in a February interview with NPR, Lilly CEO David Ricks said offering a discount for patients taking the higher doses who re-order every 45 days is an “opportunity for us to reward people who go with the program and stay on the medication.”

Some people are talking online about buying the active ingredient from China and mixing the obesity drugs in their homes. They call it the “gray market.”

Zepbound and the compounded alternatives have to be sterile for injection, so a homemade version would be challenging to make safely.

Jackson Agar in Minnesota, says the gray market is a risk his family is just unwilling to take. “Look, when you ban stuff, people are going to turn to crazy alternatives because we need this and we don’t have that much money.”

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Time is running out for people who rely on cheaper alternatives for a name-brand obesity drug. Large specialty pharmacies that were allowed to essentially make copies of Zepbound have to stop tomorrow. NPR pharmaceuticals correspondent Sydney Lupkin has more on how patients are dealing with the change.

SYDNEY LUPKIN, BYLINE: Christina and Jackson Agar, a couple in Minnesota, used to order a pizza and finish it in one night. But an obesity drug changed that.

CHRISTINA AGAR: We ate some of it the first night, and then the next day we had maybe a little bit more. And then we ended up throwing the pizza away because it had gone past the days that you could eat it. And it was so strange ’cause we have never done that.

JACKSON AGAR: No. Never.

LUPKIN: They’ve each lost about 20 pounds in six weeks. But they’re not taking Eli Lilly’s Zepbound. Their insurance doesn’t cover it. They’re taking a cheaper alternative that contains the active ingredient called tirzepatide. It’s made by a compounding pharmacy, which is a special kind of pharmacy that’s allowed to essentially make copies of drugs during shortages. Christina says she has more energy for their four kids, and Jackson stopped needing to use his sleep apnea machine.

J AGAR: It is completely life-changing to take a bite of these triggering foods and just be, like, enjoy it, say, yep…

C AGAR: Yeah.

J AGAR: …That was good…

C AGAR: Yeah.

J AGAR: …And now I’m full.

C AGAR: And now – yeah.

J AGAR: (Laughter).

LUPKIN: But on March 19, the Food and Drug Administration says compounding pharmacies will have to stop making tirzepatide because the agency declared the yearlong Zepbound shortage over. The Agars are worried. Other patients are sad, some more are just angry. In Arizona, Margot Carmichael was in denial.

MARGOT CARMICHAEL: I thought what I think a lot of people perhaps did – oh, it’ll be fine. These compounding and telehealth places are making millions off of this and helping so many people, there’s no way this is going to stop being available.

LUPKIN: It’s been confusing for patients. Some telehealth companies have been telling them they won’t be affected. Others have been offering last-minute sales as the FDA deadline nears.

JOSH FRITZLER: So March 19, we are essentially done.

LUPKIN: That’s Josh Fritzler, the chief financial officer for Olympia Pharmaceuticals, a large compounding pharmacy in Orlando, Florida. Production will stop, but pharmacies can still dispense Olympia’s tirzepatide until it runs out or expires. Olympia has made the medicine for more than 100,000 patients a month.

FRITZLER: They’re nervous. They’re scared. And we’re just hopeful that we can make enough in the time – the time being to fill patients’ scripts.

LUPKIN: Smaller compounding pharmacies, which are regulated by states, were supposed to stop in February. Many patients told NPR they have been stocking up on compounded tirzepatide. Carmichael doesn’t have health insurance right now. She says she can only afford a small stockpile.

CARMICHAEL: I don’t have the money, so I’m going to borrow the money and try to get three more months and stretch it out as long as I can and hope that six to nine months from now, there’ll be another solution.

LUPKIN: Eli Lilly sells Zepbound vials at a discount for people not using insurance, but Carmichael says they’re still too expensive. She would have to pay $600 a month for a month’s supply from Lilly. She’s been able to get three months of compounded vials for $500. To keep the Lilly discount, patients like Carmichael would also have to renew every 45 days.

CARMICHAEL: They’re making it as difficult as possible for people.

LUPKIN: Some people are talking online about buying the active ingredient from China and mixing the obesity drugs in their homes. They call it the gray market. Here’s Jackson Agar in Minnesota.

J AGAR: Look, when you ban stuff, people are going to turn to crazy alternatives because we need this and we don’t have that much money.

LUPKIN: But he says the gray market is a risk his family is just unwilling to take.

Sydney Lupkin, NPR News.

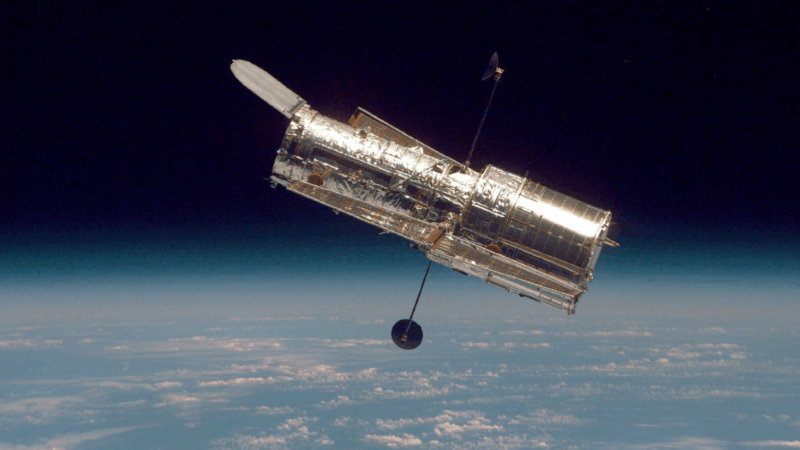

Light from satellites will ruin majority of some space telescope images, study says

Astronomers have long been concerned about reflections from satellites showing up in images taken by telescopes and other scientific instruments.

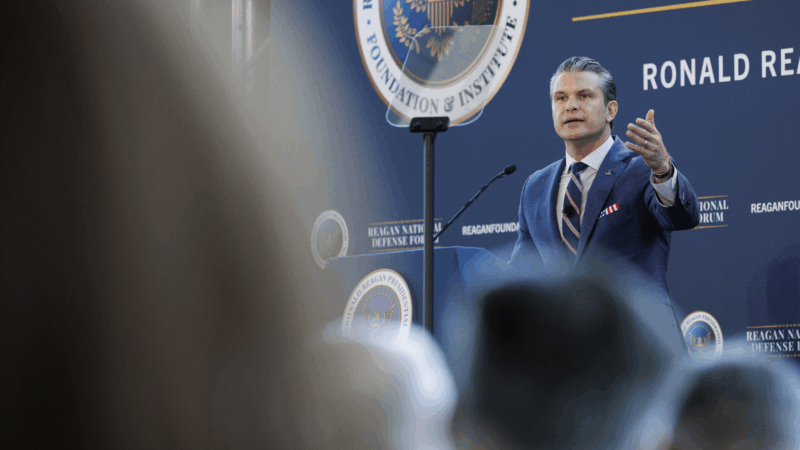

Defense Department is reviewing boat strike video for possible release, Hegseth says

In a speech on Saturday, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth defended the strikes, saying: "President Trump can and will take decisive military action as he sees fit to defend our nation's interests."

Bama, Miami in, Notre Dame out and Indiana No. 1 in College Football Playoff rankings

Nobody paying attention for the past 24 months would be surprised to see Indiana – yes, Indiana – leading the way into this year's College Football Playoff.

McLaren’s Lando Norris wins first F1 title at season-ending Abu Dhabi Grand Prix

Red Bull driver and defending champion Max Verstappen won the race with Norris placing third, which allowed Norris to finish two points ahead of Verstappen in the season-long standings.

A ban on feeding pigeons ruffles lots of feathers in Mumbai

The pigeon population has exploded — a result of people feeding the birds. For some it's a holy duty and a way to connect to nature. Critics point to health risks tied to exposure to pigeon droppings.

UN humanitarian chief: world needs to ‘wake up’ and help stop violence in Sudan

The UN's top humanitarian and emergency relief official has told NPR that the lack of attention from world leaders to the war in Sudan is the "billion dollar question".