Ozzy Osbourne, heavy metal icon, dies at 76

Ozzy Osbourne, the influential and salt-of-the-earth singer who came to be known as the Prince of Darkness, has died in Birmingham, England, according to a statement from his family.

That statement, attributed to his wife, Sharon Osbourne, and his children Jack, Kelly, Aimee and Louis, reads, “It is with more sadness than mere words can convey that we have to report that our beloved Ozzy Osbourne has passed away this morning. He was with his family and surrounded by love. We ask everyone to respect our family privacy at this time.”

Ozzy Osbourne was born John Michael Osbourne on Dec. 3, 1948, the son of John “Jack” Thomas Osbourne and Lillian Osbourne (née Unitt), the fourth of six children. The Osbournes lived at 14 Lodge Road in the Aston area of Birmingham, U.K., where Ozzy would remain for some time, including while pursuing a career as a rock and roll singer.

Once he became a star, he remained associated with the city, and returned often. He played a much-heralded final show with Black Sabbath, one of the most influential bands in hard rock and heavy music, in Birmingham just 17 days ago, on July 5.

England’s second-largest city, Birmingham was still pocked with rubble from World War II when Osbourne was growing up there; the city was a target of German bombers due to its importance as a hub of arms manufacturing.

He was, by his own admission, a terrible student — in large part due to his dyslexia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, which would go undiagnosed until he was in his 30s — and left school at the age of 15. But not before being bullied by a teacher as well as fellow students who included his future bandmate Tony Iommi, who was a year ahead of him. Iommi “might have kicked me in the bollocks a few times and given me some s***, but nothing more than that,” Osbourne wrote in his memoir, I Am Ozzy. It was around this time that he self-applied both his famed knuckle tattoo, which spelled out OZZY on the fingers of his left hand, and two smiling faces on his kneecaps, which he said brought him joy whilst sitting on the toilet.

After his unceremonious exit from school, Osbourne seemed to have little future outside of manual labor, though it would later become clear that “rock star” may have been the only viable career path for him. The “class clown,” as Iommi described him in his own memoir, was dismissed from several jobs in quick succession.

After 18 months of working in a slaughterhouse — after failing at several other trades — Osbourne was fired for beating a coworker bloody with a metal rod. The dismissal led Osbourne towards a short-lived, star-crossed career as a criminal, during which he accidentally stole baby’s clothes (it was nighttime and he couldn’t see well); a television, which he had to leave behind after it fell on him mid-burgling; and finally, while pilfering some shirts, Osbourne wore gloves that didn’t cover his thumb, leaving prints all over the scene and leading the police to his door. (“Not exactly Einstein, are we,” he recalls them saying.) He was given a three-month prison sentence, and was sent to HM Prison Birmingham, known as Winson Green, where he spent six weeks. (Twenty-odd years later, Osbourne’s “last good memory of the ’80s” would be playing a gig at the same prison.)

After his release, Osbourne’s father — despite money having been tight his whole life — took out a loan in order to buy his son a PA, the only equipment required of aspiring rock singers at the time. Then Ozzy placed an ad — “OZZY ZIG NEEDS GIG” — in the window of a local music shop. “One day, I thought,” Osbourne wrote, “people might write newspaper articles about my ad in the window of Ringway Music, saying it was the turning point in the life of John Michael Osbourne, ex-car horn tuner.”

The ad led guitarist and man-about-town Geezer Butler to his door, kicking off a brief attempt at forming a band — Rare Breed — that went nowhere, but gave Osbourne his first taste of performing. The pair, now friends, went their separate ways a few months later. But, fortuitously, the ad also led a former acquaintance of Osbourne’s to his door: guitarist Tony Iommi, accompanied by drummer Bill Ward, both recent wash-outs from the relatively vibrant English rock touring circuit. (Iommi’s previous band, Mythology, had been forced to break up due to a pot bust at their hotel during a tour, making them all-but unbookable at the the time.)

Iommi was initially dismissive of Ozzy, but the four eventually ended up rehearsing together. Despite the theatrical malevolence they would come to be known for, the group was first called something far more innocuous: the Polka Tulk Blues Band, with singer Ozzy Osbourne, guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler, drummer Bill Ward, saxophonist Alan Clark and bottleneck guitar player Jimmy Philips.

The group’s first gig was Aug. 24, 1968, at the County Hall Ballroom in Carlisle, in the northwest of the country. Immediately afterwards Clark and Philips were out, as was the band name (which Ozzy had come up with after seeing it on a bottle of his mom’s talcum powder). The four were now known as, simply, Earth. But just as they were generating some momentum from touring, Iommi left to join the big-deal band Jethro Tull as its new guitarist.

After Iommi returned to Birmingham and his bandmates, Earth redoubled its efforts, inspired by the professionalism Iommi saw during his brief detour with Jethro Tull. They also decided on a new, darker direction. The first fruits of the change would eventually come to be eponymous — but “Black Sabbath” was a song before it was a band, and a horror movie before it was a song, though Osbourne had no idea at the time (he suspected that Butler, who had come up with the song’s title, had never seen seen the film).

Booked by their first manager, Jim Simpson, the four spent pretty much all of 1969 touring — including a residency in Hamburg at the Star Club, the same place where Osbourne’s beloved Beatles had honed its chops. The group, now officially Black Sabbath, signed a record deal in early 1970, to Vertigo, an imprint of Philips.

Black Sabbath’s self-titled first record, which they’d recorded by essentially playing a quick live set, was released on Feb. 13, 1970 (a Friday, of course). It was an unexpected and runaway success, entering the U.K. charts the following month and cracking the top 10 that July.

Black Sabbath’s vaguely occult presentation was entirely superficial, but against the backdrop of Manson murders and the disintegration of the utopianist ’60s, the group’s overdriven, electrified take on the blues, its blackened psychedelia and vaguely political overtures, the image clicked. (Maybe too much; Black Sabbath would eventually be celebrated by Satanist leader Anton LeVay in a San Francisco parade. “At one point we were invited by a group of Satanists to play at Stonehenge. We told them to f*** off, so they said they’d put a curse on us,” Osbourne wrote. “What a load of bollocks that was.”) “The good thing about all the satanic stuff was that it gave us endless free publicity,” Osbourne remembered in his book. “People couldn’t get enough of it. During its first day of release, Black Sabbath sold five thousand copies, and by the end of the year it was on its way to selling a million worldwide.”

But it didn’t click for everyone — the record was near-universally panned by critics (“the album has nothing to do with spiritualism, the occult, or anything much except stiff recitations of Cream clichés,” Rolling Stone wrote) and was all-but ignored entirely by disc jockeys at the time (save the legendary John Peel, an acquaintance of Jim Simpson’s, who booked them for one of his historical, if off-air, sessions). Regardless, that year they performed on Top of the Pops, which Osbourne had watched religiously with his family at home while growing up. He was 21 years old.

The group had Paranoid, its indelible follow-up — which contains several canonical rock songs, like “War Pigs / Luke’s Wall,” its title track and “Iron Man” — written and practically in the can by the time Black Sabbath had reached its peak on the U.K. charts. Paranoid was released later in 1970; cementing the ascent of Osbourne, Iommi, Butler and Ward. After a management change the group would later come to regret — it hired Patrick Meehan, who it turned out “was taking nearly everything” and for whom they would title the album Sabotage — Black Sabbath was on its way.

The quartet’s early success ignited a decade of dizzying excess — for which Osbourne was, it would become evident, genetically predisposed. But by the end of the ’70s, the four were barely speaking.

Ozzy on his own

While the rest of the band may have had more musical chops, what Osbourne brought to the table was his showmanship. “Ozzy was a wild man,” said publicist and journalist Mick Wall, who wrote Black Sabbath: Symptom of the Universe. “He left it all on the stage, he put everything into it.”

He lived that way off stage, too, and his drug and alcohol use was a strain on the band. A breaking point came when, after a days-long bender, Osbourne fell asleep in the wrong room and slept through a gig. By 1979 he was fired from Black Sabbath.

But it wasn’t long before he found a young American guitar virtuoso named Randy Rhoads, and started working on a solo venture. Their first album together was titled Blizzard of Ozz — a sort of play on The Wizard of Oz and cocaine. The album did well in England, but the band had trouble breaking through in the U.S., despite the record containing what’s possibly his most recognizable solo song, “Crazy Train.”

Luckily, he now had a manager who knew exactly how to push the public’s buttons to get the band some attention: his future wife Sharon. The two were starting up a romantic relationship, and at the same time, Sharon was setting up stunts for Ozzy to get more attention.

“At this stage, Sharon is secretly organizing protests outside his shows, because it gets all this publicity,” said journalist Wall. “All this is stoking the fires, which is building album sales, and turning him into a major star.”

Osbourne began to be known for his wild, rock star antics. Some of these stunts (biting the head off a dove) were planned. Others, (biting the head off a bat) weren’t. But they did become part of his identity — something that, to Osbourne’s annoyance, journalists would pester him about for the rest of his life.

By 1982, Osbourne was touring the U.S. with his second solo album, Diary of a Madman. Osbourne was asleep on the tour bus when it pulled over into an airfield to fix the air conditioning when the bus driver convinced Rhoades and hair and make-up artist Rachel Youngblood to go on an airplane ride with him, promising to not pull any stunts. But in an attempt to buzz the tour bus, the plane clipped the bus and crashed. The driver, Rhoades and Youngblood died.

In his memoir, Osbourne described this moment with a mix of confusion, anger and sadness. But he and Sharon ultimately decide to continue the tour. Osbourne even kept his commitment to appear on Late Night with David Letterman, where he explained, “I’m going to continue because Randy would’ve wanted me to continue, and so would Rachel. And I’m not going to stop because you can’t kill rock and roll.”

The Osbournes

Shortly after the plane crash, Ozzy and Sharon Osbourne got married. They would later recount getting into fights, amped up by alcohol and drugs. As a father, Osbourne could be fun and lovable, until he got drunk enough that he got scary and angry. In one incident, he attempted to kill his wife in a drunken stupor.

“He lunged on me,” Sharon Osbourne told 60 Minutes Australia.” And got me down to the floor and started strangling me.”

He ended up doing a long stint in rehab, though he’d continue to have an on-again, off-again relationship with sobriety. But the family did manage to calm things down enough to start inviting cameras into their home and filming The Osbournes. The show was a hit. Premiering on MTV in 2002, and co-produced by Sharon Osbourne, it laid the groundwork for much of reality television to come (there is a fairly straight line from The Osbournes to the Kardashian empire).

The Osbournes followed Ozzy, Sharon, Kelly and Jack (eldest daughter Aimee refused to be filmed), in their day-to-day habitat — Ozzy struggling with the T.V., Kelly and Jack bickering, Sharon attempting to keep everyone in line. The show softened Ozzy Osbourne’s image enough that it wasn’t a complete shock when he was invited to the 2002 White House Correspondents Dinner and received a special shout out from President George W. Bush.

The rush of mainstream TV fame got to him. That night of the White House Correspondents Dinner, he started drinking after a long stretch of sobriety. And seeing his image constantly forced him to confront some things about his health. He’d developed a stammer. His tremors got worse. In 2020, Osbourne revealed to Good Morning America that he had Parkinson’s disease, after years of rumors about his medical condition. “To hide something inside for a while is hard,” he said. “Because you never feel proper. You feel guilty.”

As the show came and went, Osbourne never lost his ties with the music world he came from. He released solo records at a consistent clip, and he (along with Sharon, of course) ran Ozzfest — an annual music festival dedicated to the types of bands that could cite Osbourne as a primary influence: Slipknot, Slayer, Tool and more. It’s a long list of bands — and, perhaps, the most concrete example of Ozzy Osbourne’s legacy.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

Ozzy Osbourne, the prince of darkness himself, the godfather of heavy metal, has died at the age of 76. Just a few weeks ago, he sat on a throne onstage not far from where he was born and performed a final show with Black Sabbath. In 2020, Osbourne announced he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. According to a statement from his family, he died this morning, quote, “with family and surrounded by love.” NPR’s Andrew Limbong has this appreciation.

(SOUNDBITE OF BLACK SABBATH SONG, “BLACK SABBATH”)

ANDREW LIMBONG, BYLINE: Before Black Sabbath was, you know, Black Sabbath, they were just four working-class guys in Birmingham, England, playing your usual jazz and blues-type stuff. Ozzy Osbourne told NPR in 2010 that they used to rehearse across the street from a movie theater, which gave guitarist Tony Iommi an idea.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR CONTENT)

OZZY OSBOURNE: And I think it was Tony Iommi who said, isn’t it weird that people pay money to go and see scary films? Why don’t we start writing scary songs?

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “BLACK SABBATH”)

BLACK SABBATH: (Singing) What is this that stands before me?

LIMBONG: So Black Sabbath did just that. They wrote slow and dread-filled songs while Ozzy hammed it up on vocals, singing lyrics about Satan.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “BLACK SABBATH”)

BLACK SABBATH: Oh, no, no. Please God, help me.

LIMBONG: For Osbourne, the band was the beginning of a decades-long music career that would launch him to becoming one of the defining figures in rock music and eventually turn into a lovable reality TV dad. Ozzy Osbourne was born John Osbourne in 1948 in Birmingham. He had ADD and dyslexia and was disinterested in school. He knew he wanted to leave his hometown but couldn’t figure his way out. And then he heard The Beatles.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR CONTENT)

O OSBOURNE: So when I heard The Beatles, I thought, that’s it. That’s what I want to be. I want to be a Beatle, you know.

MICK WALL: Ozzy was a wild man, a showman.

LIMBONG: Music writer and publicist Mick Wall knew Osbourne and wrote a book about Black Sabbath. He says while the rest of the band might have had better musical chops, Ozzy brought the theatrics.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “PARANOID”)

BLACK SABBATH: (Singing) Finished with my woman ’cause she couldn’t help me with my mind. People think I’m insane because I am frowning all the time.

WALL: He left it all on the stage. You know, he put everything into it.

LIMBONG: Offstage, as Sabbath’s career blew up, drugs and alcohol were exacerbating growing tensions between Osbourne and the rest of the band. And in 1979, Osbourne was fired.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “CRAZY TRAIN”)

O OSBOURNE: All aboard (laughter).

LIMBONG: It wasn’t long until Osbourne teamed up with guitarist Randy Rhoads and started his solo career with the 1980 album “Blizzard Of Ozz” in honor of cocaine, his drug of choice at the time.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “CRAZY TRAIN”)

O OSBOURNE: (Singing) Mental wounds not healing. Life’s a bitter shame. I’m going off the rails on a crazy train.

LIMBONG: It was also around this time that he got romantically involved with his manager and wife-to-be, Sharon Osbourne. In the 2020 documentary “The Nine Lives Of Ozzy Osbourne,” she talked about what a rush this time was.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOCUMENTARY, “THE NINE LIVES OF OZZY OSBOURNE”)

SHARON OSBOURNE: We were just having the time of our lives, and meanwhile, Ozzy had a wife and kids back at home. So it was, you know, a lot.

LIMBONG: But she didn’t let their personal relationship get in the way of her work, pulling the strings behind the Ozzy Osbourne apparatus, which sometimes included stoking controversies to get attention. Here’s Mick Wall again.

WALL: At this stage, Sharon is secretly organizing protests outside his shows because it just gets all this publicity, turns Ozzy into public enemy No. 1. Oh, my God, don’t let your children go and see him. All this is stoking the fires, which are building album sales and turning him into a major star.

LIMBONG: Ozzy Osbourne started getting known for outlandish rock star antics like urinating on the Alamo or biting the head off a bat and a dove. And while they helped fuel his rise, it came at a cost. People kept pestering him with questions about it for years to come, including when he talked to NPR in 2010.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR CONTENT)

O OSBOURNE: Ah, next question. I’m so over the dove, the bat. You know, it’s – everybody knows what the answer is. It’s just one of them things, unfortunately, that people will remember me by when I pass on, I suppose. But, you know, the answer is, yes, I did bite the head of a dove. Yes, I did bite the head of a bat. It’s a stupid thing to do, but I did it, you know?

(SOUNDBITE OF OZZY OSBOURNE SONG, “YOU CAN’T KILL ROCK AND ROLL”)

LIMBONG: By 1982, Ozzy Osbourne – the band – was at the peak of its powers. Then in the middle of a tour, hair and makeup artist Rachel Youngblood and guitarist Randy Rhoads took an impromptu flight and died in a plane crash. It was a tough moment for Osbourne. In his autobiography, he recalls the time with sadness, anger and confusion. None of it made sense. But what he did know was that the band had to go on, that the tour had to go on. He even kept his commitments to appear on “Late Night With David Letterman.”

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, “LATE NIGHT WITH DAVID LETTERMAN”)

DAVID LETTERMAN: …Suspended?

O OSBOURNE: Well, it’s momentarily suspended. But I’m going to continue because Randy would have liked me to continue. So would Rachel. And I’m not going to stop because you can’t kill rock ‘n’ roll.

(SOUNDBITE OF OZZY OSBOURNE SONG, “YOU CAN’T KILL ROCK AND ROLL”)

LIMBONG: Shortly after, Ozzy and Sharon got married. They had kids. Family life was hard. Ozzy and Sharon got into a lot of fights amped up by booze and drugs. Ozzy got violent. He almost tried to kill Sharon once, which led to a long stay in rehab. And while he’d always have an on-again, off-again relationship with sobriety, family life got a little bit calmer, enough so that his relationship with his wife and kids became fodder for reality TV.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, “THE OSBOURNES”)

O OSBOURNE: (As himself) Don’t be – don’t drink. Don’t take drugs, son.

JACK OSBOURNE: (As himself) Dad, I never do that.

O OSBOURNE: (As himself) Please.

J OSBOURNE: (As himself) I don’t that.

O OSBOURNE: (As himself) And if you have sex, wear a condom.

LIMBONG: Premiering on MTV in 2002 and coproduced by Sharon Osbourne, “The Osbournes” gave Ozzy a new identity. Yes, he was still the prince of darkness, but he was also a doting, if sometimes fumbling, father.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, “THE OSBOURNES”)

O OSBOURNE: (As himself) Jack.

J OSBOURNE: (As himself) Yeah.

O OSBOURNE: (As himself) Can you get this [expletive] – this television to work?

LIMBONG: “The Osbournes” was a hit for MTV, and it laid the groundwork for much of reality TV. You can draw a pretty straight line from “The Osbournes” to the Kardashian empire, for example. But mainstream TV fame notwithstanding, Ozzy Osbourne still remained a hero to all sorts of metalheads and heshers and black-clothing enthusiasts. For more than two decades, Ozzy and Sharon ran Ozzfest, a music festival dedicated to the types of bands that would cite Ozzy Osbourne as a primary influence – Slipknot, Tool, Slayer, Lamb Of God, Korn, and on and on and on. And at that fest, Ozzy Osbourne would sometimes get together with his old friends from Birmingham, Black Sabbath.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

BLACK SABBATH: (Singing) Death and hatred to mankind, poisoning their brainwashed minds. Oh, Lord, yeah.

LIMBONG: This performance you’re hearing is from Ozzfest 2005, at a venue not far from where Sabbath would play their final show in 2025. But in this show, Osbourne is onstage hopping around and clapping for the crowd. A big, wide smile can’t help but break through his spooky guy shtick. And then he moons the crowd, and the rest of the band breaks into a laugh, too. And he ends the song by looking out into his sea of fans and telling them…

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

O OSBOURNE: I love you all.

LIMBONG: …I love you all. Andrew Limbong, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF BLACK SABBATH SONG, “WAR PIGS”)

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

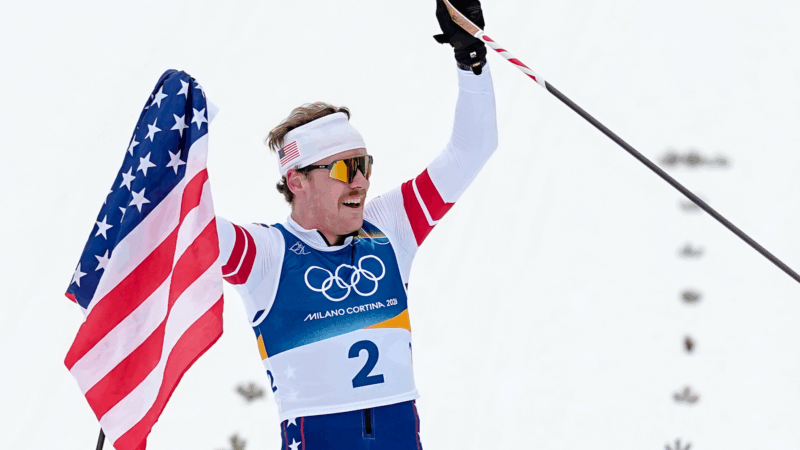

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.

An ape, a tea party — and the ability to imagine

The ability to imagine — to play pretend — has long been thought to be unique to humans. A new study suggests one of our closest living relatives can do it too.

How much power does the Fed chair really have?

On paper, the Fed chair is just one vote among many. In practice, the job carries far more influence. We analyze what gives the Fed chair power.

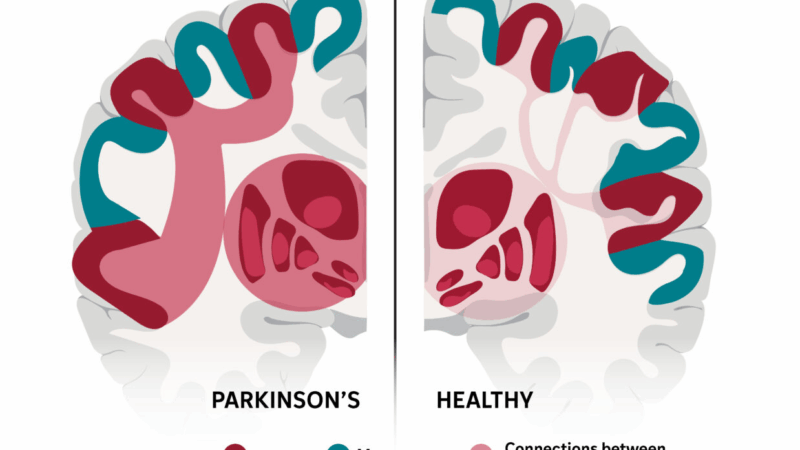

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson's disease appears to disrupt a brain network involved in everything from movement to memory.

‘Please inform your friends’: The quest to make weather warnings universal

People in poor countries often get little or no warning about floods, storms and other deadly weather. Local efforts are changing that, and saving lives.