New books this week dance between genres — and deserve your attention

Don’t even think about reading these new books — at least, not unless they shape up real quick and start respecting the venerable genre distinctions of our forebears. The last thing we want to do is encourage the kind of troublingly seductive world they represent, in which memoir can just be mixed willy-nilly with fiction, and history, and fantasy and philosophy and … well, you get the idea. We teeter on the cusp of utter madness.

Won’t somebody please think of the genres!

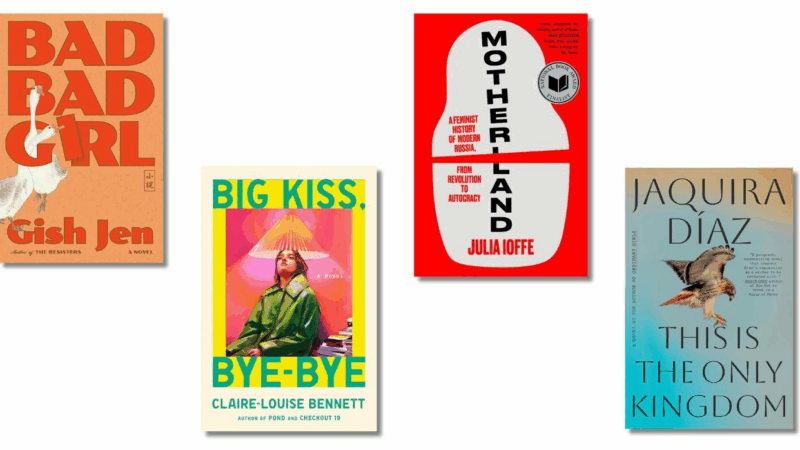

OK, I’ll admit: I’m being a bit facetious here. All six of the following notable releases do deserve your attention for one reason or another — many, precisely for their spry dance with the expectations established by the genres they invoke. But I do ask that, when you pull one of them down and crack it open, you at least spare a thought for the poor, polite label that has been left behind, flaunted and dejected, on the bookshelf where it had stood.

Looking for Tank Man, by Ha Jin

Jin Xuefei had been in the U.S. for what was to be a temporary stay, pursuing graduate studies after his time in the Chinese army, when tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square in 1989. He never returned to China; he began writing in English as Ha Jin, condemned Chinese censorship and claimed several of America’s highest regarded literary prizes. But the violent suppression of student protests at Tiananmen — his “turning point,” he told NPR in 2014 — continues to haunt him in his effective exile. In his latest novel, a fictional Chinese graduate student, studying in the U.S. years later, turns her research toward comprehending and coming to terms with the massacre — and reckoning with the urgency of keeping its memory alive.

Bad Bad Girl, by Gish Jen

Don’t call Jen’s new book a memoir, exactly. This gimlet-eyed account of a difficult mother-daughter relationship makes up too much stuff to qualify; but then, to call the book a novel feels misleading too. The book is a candid portrait of her relationship with her mother, Agnes, even if it steers more toward emotional truth than factual accuracy. We can leave these questions for the philosophers, or whoever decides the genre tags on Amazon. (Same difference?) The point is, Jen has applied her peculiar set of skills — a candid but big-hearted style once described by Fresh Air’s Maureen Corrigan as “Frank Capra-esque” — to one of the central dramas of her own life.

Big Kiss, Bye-Bye, by Claire Louise-Bennett

Louise-Bennett’s books don’t tend to lend themselves to snappy back-cover summaries. Conflict and other traditional fiction-fuels are found in them, sure; it’s just that those external stimuli often end up feeling secondary to the expansive inner life of her unnamed narrator. In her latest novel, as in Pond and Checkout 19 before it, a snapshot of the action — in this case, a woman reflecting on her memories of a fading relationship and wondering at the nature of love — doesn’t exactly scream “page-turner.” But when the pages are actually turning, the effect, as a reviewer explained for NPR, can be “unusual, and so unsettlingly pleasurable.”

Motherland: A Feminist History of Modern Russia, from Revolution to Autocracy, by Julia Ioffe

Now here’s another book with no respect for the sanctity of bookshelf labels. The veteran journalist’s first book is a mongrel mixed from memoir, history and reportage, in which Ioffe’s own memories mingle with archival dives and on-the-ground conversations. What emerges is a portrait of Russia’s past and present, viewed from the fluctuating social and legal positions of its women. For what it’s worth, the trajectory of their social standing under today’s oligarchy doesn’t appear particularly positive. Motherland is one of just five books that still stand a chance of winning this year’s National Book Award for nonfiction.

This Is the Only Kingdom, by Jaquira Díaz

The hardscrabble early years of Díaz’s life in Puerto Rico and Miami, veined as they were with poverty, casual peril and a precarious mother-daughter relationship, boasted enough drama to fill a book in their own right — and indeed they did: her first book, the 2019 memoir Ordinary Girls. In her second book, Díaz plies her skills in fiction, with a debut novel that spans generations and centers some rather shaky mother-daughter bonds of its own, amid the tumult of the Puerto Rican barrio.

The Rose Field: The Book of Dust, Volume 3, by Philip Pullman

It was in the mid-1990s Pullman published The Golden Compass, his first novel in what became the His Dark Materials trilogy. An all but immediate international sensation, the original trilogy spawned dozens of translations and a veritable host of screen and radio adaptations — and now, just about three decades later, a completed follow-up trilogy in print. The Rose Field answers the cliff-hangers of its direct predecessor, The Secret Commonwealth, and puts a bow on this heady, hefty return to Pullman’s beguiling world of daemons, witches and armored ursines.

Northeast readies for a major winter storm, with blizzard warnings in effect

New Jersey through Massachusetts could see 2 feet of snow. New York City's mayor said the city had not "seen a storm like this in a decade."

Mexican army kills leader of Jalisco New Generation Cartel, official says

The Mexican army killed the leader of the powerful Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Nemesio Rubén Oseguera Cervantes, "El Mencho," in an operation Sunday, a federal official said.

Ukraine’s combat amputees cling to hope as a weapon of war

Along with a growing number of war-wounded amputees, Mykhailo Varvarych and Iryna Botvynska are navigating an altered destiny after Varvarych lost both his legs during the Russian invasion.

University students hold new protests in Iran around memorials for those killed

Iran's state news agency said students protested at five universities in the capital, Tehran, and one in the city of Mashhad on Sunday.

Pakistan claims to have killed at least 70 militants in strikes along Afghan border

Pakistan's military killed at least 70 militants in strikes along the border with Afghanistan early Sunday, the deputy interior minister said.

Team USA faces tough Canadian squad in Olympic gold medal hockey game

In the first Olympics with stars of the NHL competing in over a decade, a talent-packed Team USA faces a tough test against Canada.