Meta and the FTC face off in court over monopoly claims

The Federal Trade Commission told a federal judge on Monday that Meta has abused its power and acted as a monopoly by acquiring rivals instead of competing fairly, opening a months-long trial seen as a test of the Trump administration’s ability to challenge the power of Silicon Valley.

To make its case, the FTC cited Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s own words. Before acquiring Instagram in 2012, Zuckerberg wrote in an internal email that he sought to “neutralize a potential competitor.” And ahead of Meta purchasing WhatsApp, in 2014, Zuckerberg wrote an email saying the messaging service represents “a big risk for us.”

In court, FTC attorney Daniel Matheson said these messages illustrate Meta’s motivation: that it used its size and influence to crush alternative services.

“They decided that competition was too hard,” Matheson said in his opening statement. “And it would be easier to buy out their rivals rather than compete with them.”

The result, Matheson argued, has been lower-quality social media apps for consumers, as Meta prioritizes preserving its power and boosting its profits above all else.

Meta’s lawyer, Mark Hansen, offered the judge a far different perspective. He said the company purchased Instagram and WhatsApp “to improve and grow them.”

Hansen argued that Meta is not a monopoly because it has never raised prices on consumers, noting all of its major apps are free — and that is because rival apps also do not charge. If a company were to charge, its app would lose customers, driving down the amount of time people spend on their platform. “The average American uses more than 40 apps every month,” Hansen said. “An app that loses minutes … potentially loses advertising revenue as well.”

The quality of Meta’s apps “has improved on every objective measure,” he said, pointing out Meta’s user growth over the years. People use more of something when it becomes better, he said: “That’s economics 101.”

Hansen argued that the FTC’s case involves the “incoherent parsing of competition” to make the case that Meta is dominant, when it is merely vying for people’s attention in a crowded online world.

A case that stretches back to 2020

The broad strokes of these arguments have been outlined by lawyers in pretrial motions over the last 4 1/2 years, but on Monday, they were made before U.S. District Judge James Boasberg, who will be presiding over the trial in Washington, D.C., for the next eight weeks.

The case, which was filed during Trump’s first term, is considered the most serious legal threat Meta has ever faced. If the FTC prevails, Meta could be forced to break up its $1.3 trillion advertising business. Experts say having to spin off Instagram and WhatsApp into separate companies could hamper Meta, since user data and advertising systems are integrated across its service.

Government lawyers plan to call a parade of witnesses, including former Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg and CEO Mark Zuckerberg, to show Meta has broken U.S. competition laws in amassing its social media empire.

The trial is expected to involve vigorous debates about technical details. The Federal Trade Commission previewed that on Monday. Attorneys for the agency said that Meta controls 78% of a market it has defined as “personal social networks” by total monthly users.

This argument is rejected by Meta, which points out the popularity of competing services like TikTok, YouTube and X. Meta says the government has “gerrymandered” a market to exaggerate Meta’s influence. Viewed by how much time people spend on apps, Meta’s market share of social media is around 30%, the company maintains.

Legal experts say the outcome of the case could hinge on how the judge views these definitions.

It is the third time in recent years the federal government has hauled a Big Tech company to court seeking to split up parts of a Silicon Valley business.

The Department of Justice has asked that Google be forced to sell off its popular Chrome browser. A phase of that trial focused on how Google must change its business to comply with competitive law is scheduled for April. And there is a second case pending against Google in which the government alleges that the company illegally monopolizes the market for online ads.

Taken together, the legal actions against the tech companies underscore growing public and political backlash against the business practices of Silicon Valley, a skepticism that was magnified when tech critic Lina Khan headed the FTC during the Biden administration. But even Republicans, and many top Trump officials, believe the tech industry power should be reined in.

In recent months, Meta’s Zuckerberg — whom Trump once threatened to imprison — has been ingratiating himself with Trump. Meta donated $1 million to Trump’s inaugural fund. The company paid Trump $25 million to settle a lawsuit over his social media account suspensions in the wake of the Jan. 6 Capitol riots. And Meta has made company changes that align with Trump’s priorities, including ending a fact-checking program and rolling back diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives.

Such moves have led to a debate in Washington about whether Trump would order the FTC to settle the case.

Andrew Ferguson, Trump’s pick who now heads the agency, has brushed aside speculation that the case would be dropped, telling Bloomberg last month: “We don’t intend to take our foot off the gas.”

Federal judge acknowledges ‘abusive workplace’ in court order

The order did not identify the judge in question but two sources familiar with the process told NPR it is U.S. District Judge Lydia Kay Griggsby, a Biden appointee.

Top 5 takeaways from the House immigration oversight hearing

The hearing underscored how deeply divided Republicans and Democrats remain on top-level changes to immigration enforcement in the wake of the shootings of two U.S. citizens.

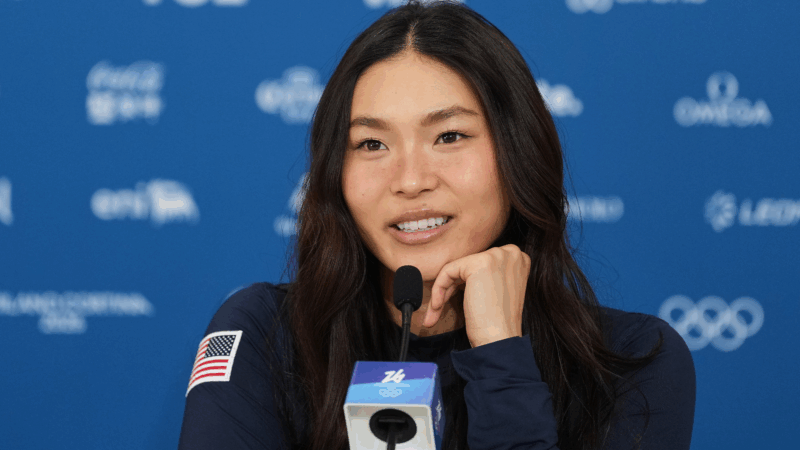

Snowboarder Chloe Kim is chasing an Olympic gold three-peat with a torn labrum

At 25, Chloe Kim could become the first halfpipe snowboarder to win three consecutive Olympic golds.

Pakistan-Afghanistan border closures paralyze trade along a key route

Trucks have been stuck at the closed border since October. Both countries are facing economic losses with no end in sight. The Taliban also banned all Pakistani pharmaceutical imports to Afghanistan.

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

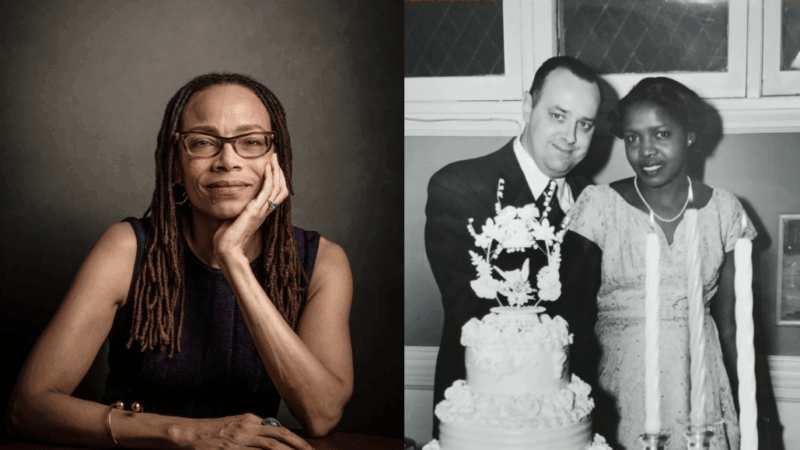

A daughter reexamines her own family story in ‘The Mixed Marriage Project’

Dorothy Roberts' parents, a white anthropologist and a Black woman from Jamaica, spent years interviewing interracial couples in Chicago. Her memoir draws from their records.