Making the case for housing as a human right

Anyone concerned about the numbers of people in the U.S. living in shelters, on the street, or doubled-up with relatives should read Maria Foscarinis’ And Housing for All: The Fight to End Homelessness in America.

A long-time policy advocate and founding director of the National Homelessness Law Center, Foscarinis makes a clear and compelling case for why housing must be recognized as a human right if we are to meaningfully address the homelessness crisis in the United States.

At just over 250 pages minus the endnotes, And Housing for All is impressively comprehensive. Foscarinis examines the origins of the crisis, explores how it has been perpetuated through inadequate response, and finally explains how we solve it. Woven throughout are details from her personal life and a legal career that spanned more than 35 years in homelessness advocacy. Importantly, she also incorporates the stories of families and individuals who have found themselves unhoused.

We meet people like Danny, who lost all the toes on his left foot and his right leg below the knee from frostbite after being forced to sleep outside — because his job stocking shelves ended at midnight, after the shelter curfew — and Dominique, a working mother of two who held both a full-time and part-time job, yet still couldn’t afford rent. Foscarinis includes stories from rural, urban, and suburban areas alike, pushing back on the misconception that homelessness primarily affects people with mental illness in big cities.

With the backing of nearly 100 pages of endnotes, Foscarinis lays out the hard facts: homelessness is a policy failure, not a personal one.

That isn’t the only myth she dismantles. One of the book’s strengths is its sustained attack on “the false narrative that homelessness is driven by personal, not systemic, failures.” With the backing of nearly 100 pages of endnotes, Foscarinis lays out the hard facts: homelessness is a policy failure, not a personal one.

It is also a bipartisan one. While Republican President Ronald Reagan infamously claimed that homelessness was a “lifestyle choice,” Foscarinis notes that the next Democratic president, Bill Clinton, “fully intended to institute harmful policies and continue the racist, punitive narratives of Reagan.” Time and again, both parties have reinforced systemic inequality through cuts to housing assistance, erosion of the social safety net, and a growing trend to treat housing as a commodity rather than a public good, the book argues.

Foscarinis helpfully grounds these policy decisions in their historical context. Beginning with the New Deal, which dramatically expanded the white middle class while explicitly excluding Black Americans, she shows how federal policy has consistently penalized people for the crime of poverty. Most devastating were Reagan’s cuts in the 1980s, which slashed federal housing funding by half. Although some reinvestments have been made since, “the Reagan cuts have never been restored to their original numbers — while the affordable housing crisis has deepened,” Foscarinis writes.

Rather than provide meaningful help, many governments have opted to criminalize homelessness instead. In 2006, Las Vegas passed a law (which was eventually struck down) “that made it a crime to offer food to anyone who looked like they might be eligible for public assistance,” she writes. Between 2006 and 2019, the National Homeless Law Center found that “laws banning sleeping in vehicles” rose by 213%, citywide bans on loitering and vagrancy increased by 103%, and camping bans went up 92%. A 2024 Kentucky law “allows property owners to shoot an unhoused trespasser — fatally” as part of its unlawful camping ban, Foscarinis’ research finds.

Foscarinis devotes her final chapters to outlining possible solutions, and chief among them is the “Housing First” model. This approach prioritizes stable housing as the first intervention, followed by support services, as needed. Finland, which uses this model, is on track to eliminate homelessness by 2027.

Though Housing First is an official U.S. policy, implementation has been limited not just due to inadequate funding, but because of the shrinking supply of affordable housing. This is particularly frustrating, given that “numerous studies have shown that Housing First not only helps people exit homelessness, stabilizes their health, and improves their lives, it also saves government money,” the book notes. Meanwhile, Los Angeles spent roughly $30 million in 2019 alone just to sweep homeless encampments — an expensive and ineffective tactic.

Central to the book’s thesis is the assertion that acknowledging housing as a fundamental human right is essential to lasting change. Foscarinis contends that only when this right is legally enshrined can effective interventions be implemented at scale. This is, she says, because “embedding the human right to housing in a country’s constitution makes its centrality clear and provides legal grounding for the right.”

Ultimately, Foscarinis argues that the biggest barrier to ending homelessness isn’t a lack of solutions. It’s a lack of political will. While “attacks on the fundamental idea of housing as a solution to homelessness,” gained momentum during the first Trump administration (and are likely to continue), And Housing for All remains hopeful. Its stories of legal victories against all odds, bipartisan collaboration on landmark legislation, and alternative models like social housing and community land trusts help plot a path forward.

As Foscarinis writes, “homelessness is indeed a choice. … It’s a choice our society makes.” And it is time we choose to be a society in which homelessness no longer exists.

Ericka Taylor is the co-executive director of Americans for Financial Reform. Her freelance writing has appeared in Bloom, The Millions, Willow Springs and Yes! Magazine.

In a historic vote, Tennessee Volkswagen workers get their first union contract

Two years ago, the successful union drive at this plant was expected to spark victories throughout the South. But now, as members vote to make their contract official, momentum has fizzled.

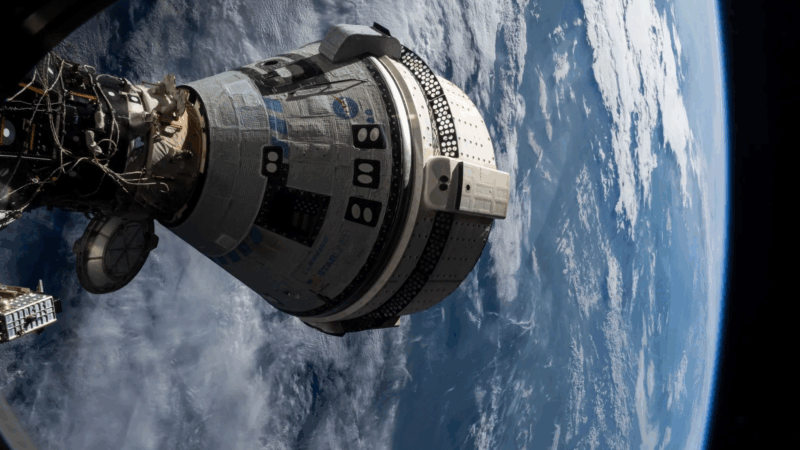

NASA chief blasts Boeing, space agency for failed Starliner astronaut mission

NASA's Jared Isaacman slammed Boeing for failures with its Starliner spacecraft, which was deemed unsafe to return its crew of two astronauts from the International Space Station

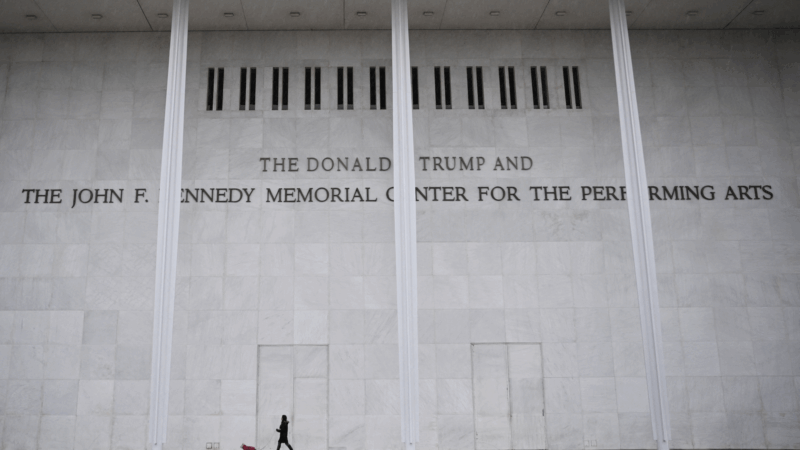

Internal memo details cosmetic changes and facility repairs to Kennedy Center

Trump announced his plans to close the Kennedy Center entirely for two years "for Construction, Revitalization, and Complete Rebuilding." The announcement came after many prominent artists canceled existing scheduled appearances.

R&B stars consider two ways to serve an audience

Two albums released the same day — Jill Scott's return from a long absence, and Brent Faiyaz's play for a mid-career pivot — offer opposing visions of artistic advancement in the genre.

Baby chicks link certain sounds with shapes, just like humans do

A surprising new study shows that baby chickens react the same way that humans do when tested for something called the "bouba-kiki effect," which has been linked to the emergence of language.

American Jordan Stolz speedskates to a third Olympic medal — silver this time

U.S. speedskater Jordan Stolz had a lot of hype accompanying him in these Winter Olympic Games. He's now got two gold medals, one silver, with one event to go.