Mahmoud Khalil told a judge his deportation could be a death sentence. Here’s why

JENA, La. — The immigration judge was looking out over her courtroom. Mahmoud Khalil was sitting at a table next to his lawyers as they tried to convince her not to order him deported to the Middle East.

“His life is at stake, your honor,” one of them, Marc Van Der Hout, told the judge.

Khalil was focused and stern. But he kept getting distracted. His wife was sitting in the public gallery a few feet away, cradling their tiny newborn son, Deen. The baby was cooing. Everyone could hear. And each time, Khalil couldn’t resist a smile.

It was a touch of levity in a courtroom otherwise heavy with the gravity of what was being discussed: Khalil’s fear that if he’s deported, the state of Israel might try to kill him.

Last month, Judge Jamee Comans ruled that Khalil could be deported because as an immigration judge she had no authority to question Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s determination that his pro-Palestinian activism at Columbia University was antisemitic and threatened U.S. foreign policy goals. Unless his lawyers believed he qualified for special protection like asylum, the judge said, she would order him expelled either to Syria, where he was born and raised in a camp for Palestinian refugees, or to Algeria, which gave him a passport because of his mother’s ancestry.

On Thursday, over 10 grueling hours behind the barbed wire of the Central Louisiana ICE Processing Center, where Khalil is being held, his lawyers called on experts via videoconference to convince the judge to grant him asylum and set him free. Here’s the heart of their argument: The Trump administration’s false, they say, and public accusations that Khalil is an anti-Semite and terrorist sympathizer have turned him into a high profile critic of Israel known around the world. Because of that, he said he fears that if he is deported to the Middle East, Israel could come after him.

“It could range from assassination, kidnapping, torture,” Khalil said during more than three hours of testimony that recalled key moments in his life, from his earliest memory in a Palestinian refugee camp near Damascus, Syria, to missing the birth of his son last month because he was locked up at the detention center 1,400 miles from his home in New York.

President Trump, Secretary of State Rubio, and other government officials “mislabeled me a terrorist, a terrorist sympathizer or a Hamas supporter, which couldn’t be further from the truth. I advocate for human rights. I never engaged in antisemitic activities,” Khalil said.

He challenged the government lawyers sitting a few feet from him to offer any evidence to the contrary. “I became, not by choice, a celebrity – someone who has a target on his back by these mislabels. This means wherever I go in the world, I will have that target.”

Judge Comans said it would be several weeks before she makes a decision on Khalil’s asylum claim. But whatever she decides will not be the final word on his fate. A federal judge in the Northeast has temporarily blocked the government from deporting him while he considers whether it violated Khalil’s constitutional right to free speech. Khalil’s lawyers are pursuing every legal option to stop his deportation and restore his green card, and have said they’ll go all the way to the Supreme Court if necessary.

During Thursday’s asylum hearing, his lawyers questioned several experts on the Middle East about why they thought Khalil would be at risk if he’s sent back there.

“The U.S. has called him a pro-Hamas agent,” said Muriam Haleh Davis, a professor of the Middle East at U.C. Santa Cruz. She said Israel has historically targeted Hamas collaborators for assassination.

Khaled Elgindy, an expert on Israeli-Palestinian affairs at Georgetown University, told the court that Khalil’s newly elevated profile as a critic of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza puts him at risk of harm or arrest.

Khalil has achieved an ability to sway Americans, Elgindy said, so “he is a direct and potent threat to Israel’s objectives. If he can be targeted by the United States government, then certainly the Israelis would perceive him in a similar light.”

Lisa Wedeen, a Syria expert at the University of Chicago, testified about the ease with which, if it wanted to, Israel could target Khalil there, given Syria’s political instability and Israel’s recent expansion of the territory it controls in the country.

“My biggest worry is that they’ll disappear him,” Wedeen said, because of “the latitude and impunity with which Israel is able to operate in Syria.”

During his testimony, Khalil said that in addition to fearing Israel, he’s also concerned that if he returns to Syria, he could be targeted by former operatives of Bashar al-Assad who’ve remained in the country since Assad’s government fell last December. Khalil, who is now 30, said he organized protests against Assad as a teenager in Syria and fled the country in 2013 after two cousins he often protested with were arrested.

The Department of Homeland Security did not call any witnesses of its own to challenge Khalil’s claim of fear. Whether it submitted written testimony is unclear.

But when he cross-examined Khalil, Numa Metoyer, a lawyer for the department, asked questions probing the level of danger Khalil would actually face.

If he feared deportation to Syria, Metoyer asked him, why had he visited the country in January?

“Before March 8 was different than after March 8,” Khalil said, referring to the date ICE agents arrested him, leading President Trump to call him a “Radical Foreign Pro-Hamas Student.”

“Because attention was brought to you here in this case, now you have been targeted by the Israeli government?” Metoyer asked.

The Department of Homeland Security did not immediately respond to questions about Khalil’s asylum claim. After the hearing, his lawyers said they hoped the judge will consider it “with an open mind.”

During his testimony, Khalil did too.

“Although I have no faith in the immigration system,” he said, “I hope that my presence here is not merely a formality.”

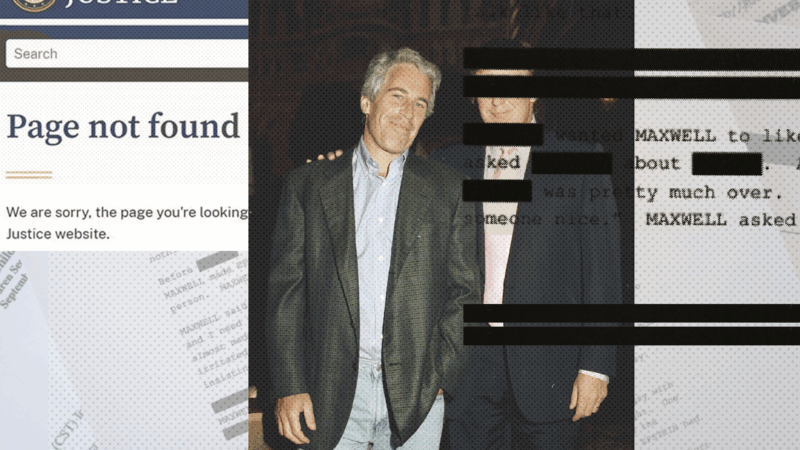

Justice Department publishes some missing Epstein files related to Trump

The Justice Department has published additional Epstein files related to allegations that President Trump sexually abused a minor after an NPR investigation found dozens of pages were withheld.

Pregnant women in ERs took less Tylenol after Trump autism warning

A study in The Lancet finds that pregnant women in emergency rooms used less Tylenol after President Trump said it could raise their babies' risk of autism. Scientists say there is no proven link.

Mixed reactions, including relief, greet news the Coast Guard is buying BSC campus

The U.S. Coast Guard will take possession of the 192-acre campus in the northeast corner of Birmingham’s Bush Hills Neighborhood and will begin work to refit it as a training center for officers and enlisted personnel.

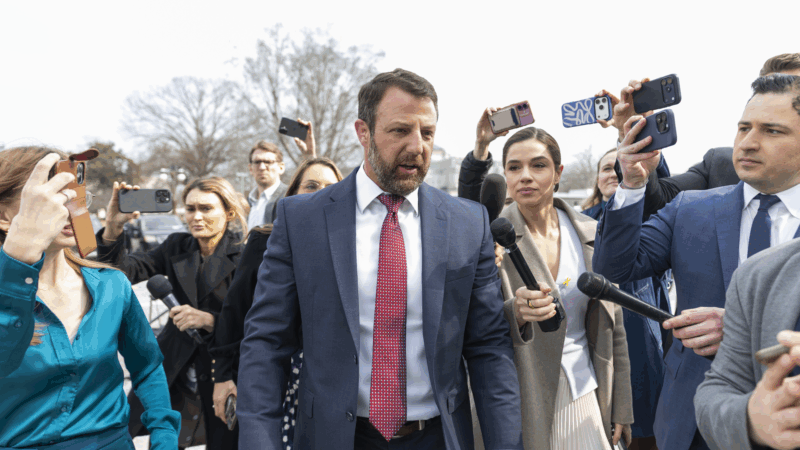

What you need to know about Sen. Markwayne Mullin, Trump’s new pick to lead DHS

President Trump announced Thursday that Sen. Markwayne Mullin, R-Okla., is his pick to replace Kristi Noem as the head of the Department of Homeland Security.

Travel industry pushes Congress to end DHS shutdown and pay federal security workers

With the busy spring break travel season looming, travel and aviation industry leaders urged Congress to end the stalemate over DHS funding before workers at TSA and ports miss a full paycheck.

Trump fires Kristi Noem as DHS chief, names Sen. Markwayne Mullin to replace her

President Trump has fired his homeland security secretary, Kristi Noem, and said Markwayne Mullin, a senator from Oklahoma, would replace her.