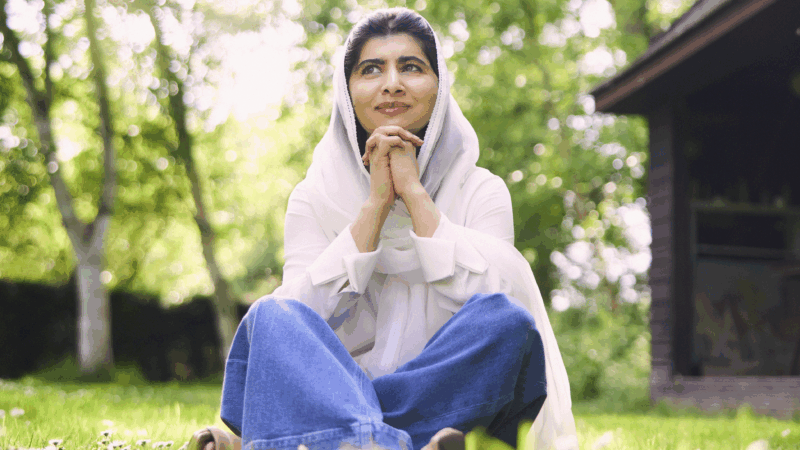

Just because she won a Nobel doesn’t mean Malala didn’t break some rules in college

When the Taliban closed schools and banned women from public life in Pakistan’s Swat Valley, a schoolgirl named Malala Yousafzai spoke out. But activism nearly cost Yousafzai her life; in 2012, when she was 15, she was shot in the head while riding home on a school bus.

Yousafzai survived the assassination attempt, but her life changed completely. Suddenly she was a symbol of resistance to the Taliban — praised, politicized and picked apart. When she was 17, she became the youngest person ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, an honor that weighed on her as she went off to Oxford University a few years later.

“I always have felt that now I need to live up to the expectation [of the Nobel],” Yousafzai says. “It was given for the work I had done, but it was also given for the work that is ahead of us. … I have to work for the rest of my life to prove that it was well deserved.”

Prior to college, Yousafzai had never been away from her parents or lived on her own. At Oxford, she struggled to know who she was as a person. “This was the first time I allowed myself to be more of myself, to really just test it. … Am I funny? Am I not? What do I enjoy?” she recalls.

Yousafzai chronicled her childhood in the 2013 memoir, I Am Malala. In the new memoir, Finding My Way, she writes about her life at Oxford and beyond. It’s the story of a college student who, like many others before her, tries marijuana, fails exams and falls in love for the first time. But it also reveals Yousafzai’s efforts to deal with the trauma of the attack she had survived years earlier.

“When you face violence, harm and trauma yourself, you understand how terrible and horrible it is,” she says. “Whether it’s girls being banned from school in Afghanistan, or girls’ schools being bombed in Gaza, or children being forced into labor, or girls being married off. … I just hope that we can create a world without any war and terror and harm for children.”

Yousafzai’s foundation, Malala Fund, continues to advocate for girls’ education worldwide.

Interview highlights

On illicitly climbing onto a rooftop in college

That moment just felt surreal. I was so scared that I might be kicked out of college for this. … I was terrified that being an advocate for education and then getting in trouble and getting kicked out. … For me it was wanting to disobey rules. I thought I had to live up to expectations and be a certain way. I could never get in trouble. I thought if this is something that puts me in the “cool kids” category or the “rebellious kids” category, I wanted to give it a try. I wanted these college years to be that experience that I otherwise would never come across.

On having a bad reaction to smoking marijuana, which triggered PTSD

The bong incident just turned out to be an experience not that I had imagined. I had heard cool things about it and of course it’s different for everybody. In my case, there was this unaddressed trauma. The memory, the visuals, everything had been there. My brain had tried to suppress them because it’s a moment of fear that you do not want to see again. When the bong incident happened, my body froze and I was reliving the Taliban attack. I could see the gunman. I thought this is happening all over again. I often say that I received my surgeries and I recovered so quickly from the Taliban attack, but when this happened I realized maybe I actually had not fully recovered.

On struggling with anxiety and depression, seven years after the attack

I just felt so disappointed with myself that somebody who faced a Taliban gunman was somehow now scared of these small things. It was all trivial stuff that made no sense to me. I thought that I had lost my courage, that I was not brave enough. … I felt like an imposter. And then one of my friends suggested that I see a therapist.

Growing up I had seen many girls lose the opportunity to complete their education and their dreams to become a doctor or engineer because they were married off. Marriage, that was the last thing I wanted to think about.

Malala Yousafazai

On why she was initially against marriage

Growing up I had seen many girls lose the opportunity to complete their education and their dreams to become a doctor or engineer because they were married off. Marriage, that was the last thing I wanted to think about. I did not want to get married. It was not a cool thing. If you wanted to have a future as a girl you wanted to keep yourself away from marriage for as long as you could. … It just meant more compromises for women that you had to readjust to the husband’s family and you had to pray that the husband turns out to be a nice, respectful person.

On reading feminist authors before deciding to get married

When I saw Asser I immediately fell in love with him. I knew that I wanted to be with him. So I felt like I was sort of holding his hand … while I was looking on the other side trying to figure out what is marriage and all these things about and am I ready or not? I knew that we had to be married because in our culture for two people to be together you have to be married. But then marriage just felt like a very heavy topic for me. I even went to read some books. … I was like, please Virginia Woolf, help me, bell hooks, can you share a few words of wisdom? I was looking for an answer, like, just someone tell me yes or no. What I realized in the process was it is about understanding the history of these things. It’s about the culture, the context, but more importantly then, it’s about the two people who decide to be together. What is their mutual understanding? And I realize that Asser was the right person.

Heidi Saman and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

The FDA creates a quicker path for gene therapies

The Food and Drug Administration aims to evaluate treatments for rare diseases based on plausible evidence that they would work — without requiring a clinical trial first.

BAFTAs apologize after guest with Tourette syndrome uses racial slur during ceremony

A man with Tourette syndrome shouted a racial slur and other offensive remarks during the BAFTA awards ceremony Sunday. The BBC did not edit out his outbursts in its delayed broadcast.

‘Everything was in pieces:’ Lindsey Vonn describes grueling surgery on broken leg

In a recent video, the Olympic skier credits her surgeon with saving her leg from potential amputation.

A new lawsuit alleges DHS illegally tracked and intimidated observers

Observers watching federal immigration enforcement in Maine who were told by agents they were "domestic terrorists" and would be added to a "database" or "watchlist" are now part of a new federal class action lawsuit.

Kate Hudson on regret, rom-coms and finding a role that hits all the notes

Hudson always wanted to sing, but feared it would derail her acting career. Now she's up for an Oscar for her portrayal of a hairdresser who performs in a Neil Diamond tribute band in Song Sung Blue.

A powerful winter storm is roiling travel across the northeastern U.S.

Forecasters called travel conditions "extremely treacherous" and "nearly impossible" in areas hit hardest by the storm, and air and train traffic is at a standstill in many parts of the region.