Is it ‘Made in USA’? The answer can be complicated

As tariffs reshape supply chains, more Americans may be checking packaging for the “Made in USA” label, either to sidestep import taxes or to support domestic businesses. But intricate trade rules and far-flung manufacturing networks can mean the country-of-origin stamp may tell only part of the story.

The label “Made in USA” means that all or virtually all of a product — including its parts and assembly — must originate in the United States. However, “virtually all” doesn’t mean everything has to be U.S.-made.

“‘Made in U.S.A.’ is a very specific, very high standard,” says Marcus Eeman, senior manager of customs at global logistics firm Flexport.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, which oversees country of origin claims in marketing and advertising, to qualify for the label, U.S. authorities must determine that a product’s final assembly or processing has taken place in the U.S., and that a significant portion of its manufacturing costs must also be incurred domestically.

“You probably will never see a car that says ‘Made in America,’ but you will see it that says ‘Assembled in America,’ probably with some foreign components as well,” Eeman explains.

That said, some foreign components are allowed to still qualify as “Made in U.S.A.” — as long as they don’t substantially transform the product. Eeman explains that this concept dates back to a 1908 Supreme Court case involving Anheuser-Busch, which used cork from Spain to cap beer bottles. The Court ruled that the cork didn’t transform the product, since it didn’t change the beer’s name, character, or use.

Determining a product’s country of origin through the “substantial transformation” test can be tricky, Eeman says. “There is a case where a bulk block of lipstick material was shipped from Italy to China,” he says. In China, the block was melted, shaped and packaged. Despite this, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) ruled that the country of origin was still Italy.

The U.S. Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration offers other examples. Ingredients such as sugar, flour, dairy, and nuts can be imported, but once they are baked into cookies in the U.S., the final product is considered substantially transformed — and may carry a “Made in USA” label, it says.

However, bilateral trade agreements can override these rules. Under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), for example, a one-time importation of a commercial product valued under $2,500 is exempt from country of origin labeling requirements.

Then, there is “Assembled in USA.” The FTC says, “A product that includes foreign components may be called ‘Assembled in USA’ without qualification when its principal assembly takes place in the U.S. and the assembly is substantial.”

But not all assembly counts. The FTC specifies that a “simple ‘screwdriver’ operation” doesn’t qualify. For instance, importing components such as a motherboard and hard drive and merely assembling them into a computer in the U.S. would not justify an “Assembled in USA” label. A more accurate claim would be “Made in U.S. from Imported Parts.”

“You’ll likely never see a car labeled ‘Made in America,’ ” Eeman adds, “but you might see one labeled ‘Assembled in America,’ often with some foreign components.”

Things can get even more complicated when it comes to food products, specifically pork and beef.

In 2015, Mexico and Canada successfully challenged U.S. country of origin labeling (COOL) requirements for pork and beef at the World Trade Organization. The WTO found that rules that muscle cuts of beef and pork, and ground beef and pork must be labeled with their country of origin unfairly disadvantaged foreign producers, leading Congress to repeal the COOL requirements for those meats.

“Beef and pork, which were once required to be labeled, [now] don’t have any country of origin labeling requirements,” says Thomas Gremillion, director of food policy at the non-profit Consumer Federation of America. “You can take a cow that spends its entire life in Mexico… ship it back across the border, slaughter it the same day, and call it a ‘Ground beef product of the USA.'”

Still, Pam Lewison, agriculture research director at the Washington Policy Center, notes that most U.S. meat is in fact produced domestically. But for other food items, she says, country of origin labeling remains complicated. “Ideally, you want to see a label that says the product was made, produced, and sourced from the United States.”

She adds a word of caution to consumers: “If you’re buying asparagus in December, you shouldn’t fool yourself about where it’s coming from — it’s not coming from here.”

Immigration officials to testify before House as DHS funding deadline approaches

Congressional Democrats have a list of demands to reform Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But tensions between the two parties are high and the timeline is short – the stopgap bill funding DHS runs out Friday.

Hospitals are posting prices for patients. It’s mostly industry using the data

The Trump administration pushed for price transparency in health care. But instead of patients shopping for services, it's mostly health systems and insurers using the information for negotiations.

How the use of AI and ‘deepfakes’ play a role in the search for Nancy Guthrie

As artificial intelligence becomes more advanced and commonplace, it can be difficult to know what's real and what's not, which has complicated the search for Nancy Guthrie, according to law enforcement. But just how difficult is it?

‘E-bike for your feet’: How bionic sneakers could change human mobility

Nike's battery-powered footwear system, which propels wearers forward, is part of a broader push to help humans move farther and faster.

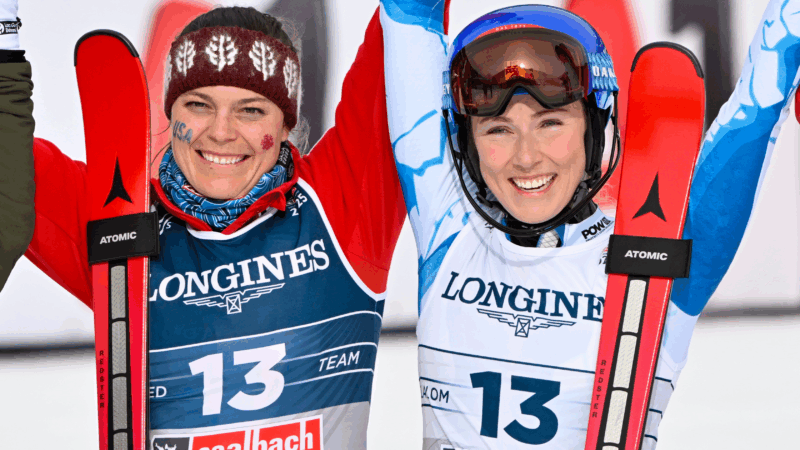

Mikaela Shiffrin set to ski for the first time in the Olympics in team combined event

The team combined event pairs a downhill skier with a slalom skier. The top U.S. duo — the slalom star Shiffrin and Breezy Johnson, who won gold in the downhill on Sunday — is a medal favorite.

Buddhist monks head to DC to finish a ‘Walk for Peace’ that captivated millions

The group of Buddhist monks is set to reach Washington, D.C., on foot Tuesday. The monks in their saffron robes have become fixtures on social media, along with their rescue dog Aloka.