India’s honk-happy drivers are switching to even louder horns

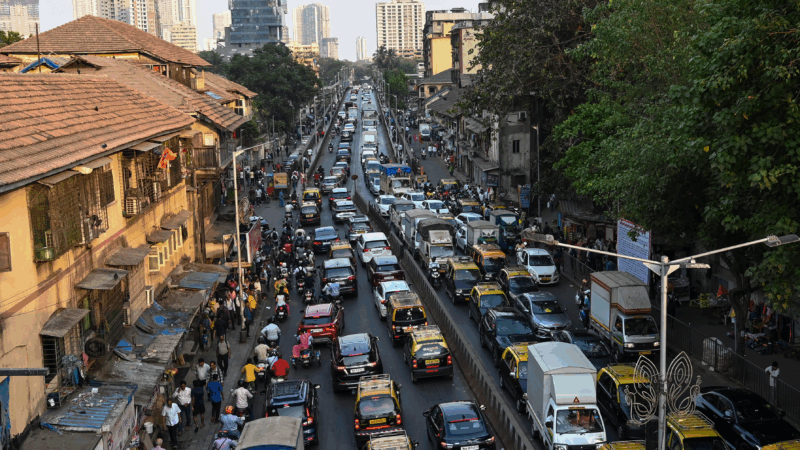

MUMBAI, India — If there is anything as inescapable in this Indian megacity as the humidity, it’s the noisy traffic.

Drivers honk at pedestrians and each other. They honk to beat the traffic signal, or when the signal beats them.

In one not-so-scientific survey NPR conducted at an intersection near its bureau here at 3 p.m. one day in August, there were 27 honks in just one minute. Traffic constable Vikas Rahane, who was on the afternoon-to-evening shift, says that number is the “normal” amount, but it’s only going to go up.

“It’s the peak-hour evening traffic that gets you,” he said, referring to the times from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m.

Sometimes, he can’t sleep. It has even caused hearing loss in some of his colleagues.

Under Indian laws, cops like Rahane can penalize drivers up to $25 for honking too much or without reason. But as his senior officer, Subhash Shinde, said: Mumbai roads are often so chaotic, they can focus on little beyond keeping the traffic moving and the pedestrians safe. “In the order of priorities, this one [honking violations] would rank somewhere between six and 10,” said Shinde.

A 2019 study found that the average noise in Mumbai is often more than 80 decibels — rivaling some of the busiest streets of Manhattan. That’s like listening to a vacuum cleaner day and night — but louder. The World Health Organization recommends that it should not exceed 55 decibels.

Traffic is among the biggest culprits, as it is in most international cities. But in India, there’s another dimension to this problem.

“Many people here believe it’s impossible to drive without honking because if you don’t honk, no one will move out of your way,” says Sumaira Abdulali, founder of the nonprofit Awaaz Foundation that campaigns to control noise pollution. “Whereas the fact is when everyone’s honking no one moves out of your way anyway.”

When vehicles don’t move, drivers honk more. This noise blends with that coming from road, railway, bridge and housing construction projects, which often go on day and night in Mumbai, year-round. In a city of 20 million people, where most sidewalks are dilapidated, getting stuck in slow-moving traffic can sound as loud as a rock concert.

“The horns go up to 120 decibels, and sometimes even a little bit more than that,” says Abdulali. “And they are definitely getting louder.”

NPR spoke to more than a dozen drivers of bikes, auto-rickshaws and taxis for this story. Nearly everyone said that they find the standard-issue horn inadequate. Some pointed to a local hub where they can shop for extra-loud horns: the CST Road marketplace in suburban Mumbai.

Hundreds of shops at CST Road are crammed along half a mile of bumpy road with cackling traffic. They specialize in automobile spare parts — headlights, LED screens, music systems, bumper stickers — their wares often spilling out on the pavement.

One of the shopkeepers offers a demo of the horns they sell: a flat one, a punchy one, a musical one, one that sounds like a barking dog, and another that sounds like someone screaming. They call the last one “the ladies.”

Noor Mohammed, who owns a shop here, says their bestsellers can be classified in two types: “titi” horns and “pom pom” horns. The first has a flat tone and is used mostly in bikes, rickshaws and hatchbacks. The second is an air-pressure horn, mostly used in SUVs and buses.

In recent years, he says, there’s been a spike in demand for the “pom pom” horn. “Pedestrians don’t listen if you use the “ti ti.” They make way when you use the high-pressure pom pom horns,” Mohammed says. Others say those who upgrade to loud horns just want to show off.

A new “pom pom” horn costs less than $10 and can last a year or longer, depending on how much you beep. Such is the demand, a league of horn-reviewers has spawned online. Many specifically seek the horns in the Hyundai Creta, a subcompact SUV, because, as one reviewer describes them, “it is very, very, very strong.”

One can make a case for their popularity, says Gagan Choudhary, founder of the automobile news website Gaadify. “In India, we chat a lot and play music on a high volume inside the car. Because of that, usually the horns with more bass are heard a little easier,” he says.

Choudhary adds that vehicle manufacturers understand the needs of Indian drivers. Some motorbike-makers have made their horns louder in recent years, and some car-makers have made their horns punchier, with more bass.

To confirm, NPR emailed more than a dozen motorcycle and car manufacturers. Mercedes-Benz said in a statement, “We understand that horn usage in India is often more frequent and serves as an essential communication tool on the roads … unlike many countries where horns are primarily used to signal caution or alert other drivers.” That is why their car horns for India “are slightly adapted for enhanced durability.”

Other companies did not respond.

But all these louder — and more durable — horns haven’t increased road safety. More than 150,000 people die in road accidents in India every year. The numbers get grimmer by the year.

A few years ago, the country’s road and highways minister, Nitin Gadkari, proposed a solution to the country’s noise crisis: Replace all vehicle horns with ones that play Indian classical instruments, like flute, harmonium or violin, “so it is gentler on the ear.”

Environmentalist Abdulali says that would be a disaster. “I can only imagine what’s going to happen when you have various types of music blaring because somebody is bored or unhappy.”

The only way ahead, she says, is to understand noise as a public health issue and combat it by enforcing laws and promoting civic sense. Until that happens, Abdulali says, she will keep raising her voice — and hope that someone hears it above the din.

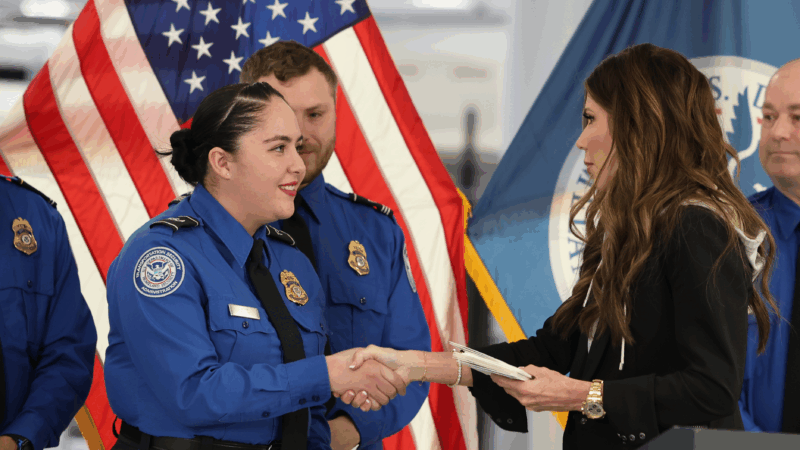

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

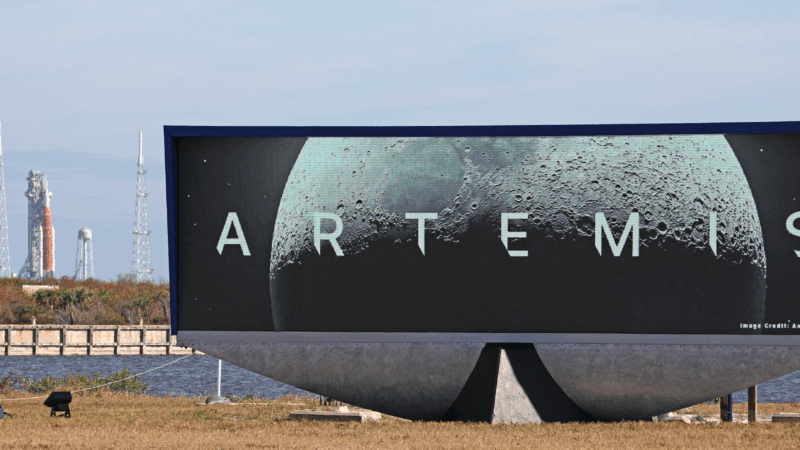

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

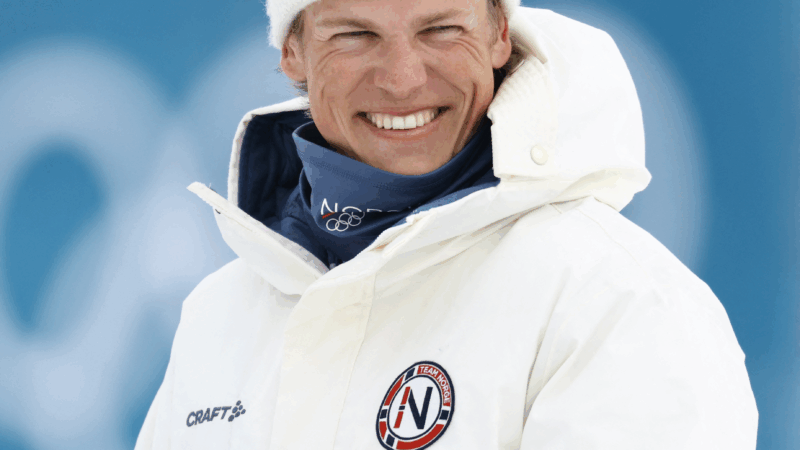

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.