In New Orleans, memories of Katrina remain vivid 20 years later

20 years ago last week, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, about 50 miles southeast of New Orleans. Thousands of people had evacuated in advance of the monster storm. But many stayed behind. And even before the storm made landfall, the levees protecting New Orleans began to fail, overwhelmed by heavy rain and massive storm surges.The flooding was catastrophic and the scars from Katrina, which killed nearly 1,400 people across the Gulf Coast, are still evident today.

Katrina remains the costliest storm on record and recovery has come in fits and starts.

In New Orleans, entire neighborhoods were decimated.

The disaster challenged the government’s responsibility to its citizens and their citizens’ responsibilities to each other.

In the city’s Ninth Ward, which is in the easternmost part of New Orleans, residents told us they couldn’t imagine living anywhere else. Here are some of their stories:

Eugene Green Jr., (age 67)

Current New Orleans City council member and realtor Eugene Green Jr.’s home in the Gentilly neighborhood was flooded during the storm. At the time, his children were 15, 8 and 6. He relocated his family to Houston but returned weekly to New Orleans to help rebuild and encourage others to come back. Six months later, his family moved back home.

“Sometimes it’s hard to remember that people were kept away from their houses for a year,” Green said. “If you had a job and lost it, you had to get one somewhere else. A lot of people also lost their homes because the Road Home Program gave money based on property value. In low-income areas, you couldn’t get as much money. So many people couldn’t return.” (Road Home was a housing recovery program funded by the federal government.)

Marguerite Doyle Johnston (age 67)

An office administrator at the Southern University at New Orleans, Marguerite Doyle Johnston has long been known for helping her neighbors in times of crisis. Her roots in the Desire neighborhood go back generations. She’s been flooded out multiple times but still lives on Desire Street.

“Prior to the Hurricane, my family and I used to give these big block parties,” she said. “We’d have senior citizens in the community come sign up in the event of something like this [Katrina]. But what happened was when they see a hurricane was about to hit, OPD said ‘Marguerite, don’t you break in that school again.'” That’s because she would break into locked school buildings to secure shelter for those most in need.

Doyle-Johnston said that New Orleans will always be her home. “I was on one of the boats with the police officers when I see the back of my house, the chimney, all of that, caved in. It was gone. I knew I was going to build back – that was my heritage. My grandfather passed it down to us.”

Adolph Bynum Sr. (age 86)

Bynum lives in Tremé but spent a half century working in the Desire community, running Bynum’s pharmacy.

“Everyone knew about Bynum pharmacy,” he said. “We set up the people of low income. We had layaway for toys. Christmas eve was our busiest day of the year,” Bynum recalled. “I cashed checks on welfare day and social security day. We had a dentist, a doctor’s clinic, a deli. Everyone came to Bynum’s because we took the electric bills, the water bills. Whatever you needed, we had it.”

He offered a $20 credit line and knew most customers by name. Though his home didn’t flood, the pharmacy didn’t survive Katrina. After the storm, he would go on to make a career out of restoring historic homes.

Brittany Penn (age 36)

Penn was 16 when Katrina hit. She lives three doors down from her current business: a hair salon and rental units she owns on Desire Street.

Her parents , who managed property, insisted on fixing up their flooded home. Penn helped scrub the walls and still lives there today. She later turned that experience into a career.

Using profits from her hair extension business, she invested in real estate in the neighborhood.

“We used to be able to do everything in our community,” she said. “Everything was done in the Ninth Ward. After Katrina, seeing all these empty houses, so many vacant houses, it’s really different.”

Both of her parents have since died of cancer.

Kenneth Avery (age 74)

Avery grew up in an affordable housing development in the Desire neighborhood and has lived through multiple hurricanes. His home in Gordon Plaza flooded but he would rebuild using his insurance.

Later, the property was declared a Superfund site due to underground hazardous waste, and he was bought out.

“The people in the neighborhood saw unusual things going on and hundreds of people were dying from cancer,” Avery said.

He now lives in a new home in Gentilly.

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

I’m Michel Martin at WWNO in New Orleans, where 20 years ago today, Hurricane Katrina made landfall. Within hours, a massive storm surge had breached the levees, leading to catastrophic flooding in the city and almost 1,400 deaths. As well, it led to years of exhausting efforts to bring the city back and even questions about whether it should be brought back at all.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR CONTENT)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: People on the rooftops and some people still in their house. We rescued a young lady. She was in the house. She couldn’t get in the attic. And I don’t know how she survived, but she made it.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: Two babies have died. A woman died. A man died. We haven’t had no food. We haven’t had no water.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

GEORGE W BUSH: Katrina exposed serious problems in our response capability at all levels of government. And to the extent that the federal government didn’t fully do its job right, I take responsibility.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

MICHAEL BROWN: I very strongly personally regret that I was unable to persuade Governor Blanco and Mayor Nagin to sit down, get over their differences and work together. I just couldn’t pull that off.

MARTIN: That was former FEMA Director Michael Brown, President George W. Bush and voices from NPR’s coverage 20 years ago. But beyond the physical damage to a major American city and elsewhere, Katrina was a disaster that became a national tragedy, one that set off fierce debates about race and class, about which lives seemed to matter and which didn’t, about the government’s responsibility to its citizens and its citizens’ responsibilities to each other. That’s why we spent the week here reporting in and around New Orleans, asking people for their memories and stories about how their lives have changed. We met up with one group in the Ninth Ward.

I’m looking at the Desire Florida Multi-Service Center, and you can tell that it’s new. But if I look across the street, I see empty lots. I see houses, don’t get me wrong. I see houses. I see houses where clearly people live there, and they’re taking care of them. But there are empty lots with some overgrown weeds, for sale signs on some of these empty lots. And you can tell that every one of these lots represents a place where a family used to live, and for whatever reason, they were never able to come back. They were never able to rebuild.

This is council member Eugene Green’s area. He asked some of his neighbors to stop by.

EUGENE GREEN: Well, we’re at the Desire Florida Multi-Purpose Center (ph), which is a multipurpose center in the midst of a community that, some time ago, was one of the more thriving communities in our city.

MARTIN: He says Katrina is a time marker for just about everybody here. They all remember the before times.

GREEN: In this community, there are maybe 3,000 individual lots. But this community’s school was devastated ’cause there are three schools here. There’s Delgado, there’s Carver and there was, at the time, even Moton.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: [inaudible] Lockett.

GREEN: And Lockett. So you had four schools in this community, and all of them were flooded, and it took longer to get schools back online because many of them had to be torn down and rebuilt. And some of them still haven’t been rebuilt.

MARTIN: Marguerite Doyle Johnston never left.

MARGUERITE DOYLE JOHNSTON: Prior to the hurricane, my family and I used to always give these big block parties. And what we would do, we’d have senior citizens in the community to come sign up in the event of something like this. We didn’t never think about this. But what happened was when they said, a hurricane was about to hit, and OPD said, Marguerite, don’t you break in that school again, ’cause every time I break into school to put the people in the school for safety reasons.

MARTIN: As someone who traces her roots in the city back to the 1920s, she said she considered it her responsibility to make sure people were safe, even if it meant breaking into a school.

DOYLE JOHNSTON: After that, I knew I was going to build back, so I had to make a choice of either I bring my business back or I build my home. And it was to build my home because that was my heritage. My grandfather, you know, they sent it down to us.

MARTIN: Did that program help you build at all? That program – what they call it? – the Road Home Program. Did that help at all?

DOYLE JOHNSTON: It helped some. We came back every day because I owned the building on Canal Street. We came back every day to help, just to help. In my house, I was on one of the boats with the police officers when I seen the back of my house, the chimney, all of that just caved in. It was gone.

MARTIN: Did you ever think of leaving?

DOYLE JOHNSTON: No, I did not.

MARTIN: (Laughter).

DOYLE JOHNSTON: Not doing that.

MARTIN: I wish I could describe the look you just gave me (laughter).

DOYLE JOHNSTON: This is my heritage. This is – they’re going to have to blow the Ninth Ward off the map in order for me to leave.

MARTIN: Johnston said, back in the day, there was never a need to leave the neighborhood.

DOYLE JOHNSTON: The only place our community at the time can go and get groceries or go get medicine was from Mr. Bynum’s. He would give us – senior citizens, if they don’t have the money and stuff, he would give them credit. So everybody knew about Bynum’s.

MARTIN: She’s talking about Adolph Bynum. Everyone knew his store.

ADOLPH BYNUM: Everyone knew about Bynum Pharmacy. We set up the people who have low income. I sat up layaway for toys, and we would cash checks. on welfare day and Social Security day.

MARTIN: So it wasn’t just a pharmacy, it was a community center.

BYNUM: It wasn’t a – it was a community center.

MARTIN: It was a community center.

BYNUM: We had a dentist. We had a doctor clinic. We had a deli. And everyone came to Bynum’s.

MARTIN: Bynum is 86 years old now and has been successful in his second career restoring historic homes. But you can hear in his voice how much he misses his pre-Katrina life.

BYNUM: And during the Christmas days, they would close Desire Street, and everyone would skate.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: Skate.

MARTIN: (Laughter).

BYNUM: And where did they buy their skates? Was at Bynums. I really miss it. I used to love getting the mail. And I used to have a credit line up to $20. And if you cashed your check – and I made ID cards where they wouldn’t have to have a driver’s license or nothing else because I knew everyone.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: We knew everybody.

MARTIN: I’m sorry. Did the store make it?

BYNUM: The store didn’t make it.

MARTIN: More to the point, the community around his store disappeared, uprooted first by the flood and then by the need to survive to get children back into school and find steady work.

BYNUM: I still miss my store. I still miss the people coming in because they would look for things like goose grease and honey. And they will ask me, where can I find goose grease and honey? And I ask pharmacies, where can you get the goose grease and honey? They said, well, what is that? What is it? You know? It was a remedy that my father concocted.

MARTIN: What was it for?

BYNUM: Colds for babies.

MARTIN: Kenneth Avery (ph) also stopped by to share his story. He was born and raised on Desire Street.

KENNETH AVERY: Came up in a housing development. A lot of people would say the project, but it’s really a development because it develops you to move on to other things and better things.

MARTIN: OK.

AVERY: Which I think that I had accomplished.

MARTIN: After raising three children – now all professionals who live elsewhere – Avery planned to weather Katrina at home. But when he realized how serious it was, he took shelter in the Superdome. The journey there was harrowing.

AVERY: It was kind of devastating wading in the water and seeing people that had drowned in the water, and they tied some people onto telephone poles…

MARTIN: Oh, God.

AVERY: …So they wouldn’t float away. When I got to the bridge, by the dome, they had people in wheelchairs – they were – they had to pass away. And it took days for them to come and relieve them and to rescue them.

MARTIN: For a while, he went to live with a daughter in Texas, but once his insurance came through, he went home.

AVERY: It was challenging at first. A lot of the materials and stuff went up in price because people were kind of, like, price-gouging. They knew that people needed materials to build their home, so they set their own price. And that’s what happened.

MARTIN: He would end up moving twice, first because of Katrina, and second because he says his house was built on a toxic waste site.

AVERY: The house – it was supposedly houses built for low- to moderate-income. First-time home buyers, as they said, it was. And they never said that, OK, all this toxic stuff is under your house. But we knew something was wrong because women were having miscarriages, children were dying. Dogs couldn’t live in that area because they were low to the ground and breathing all this debris.

MARTIN: Given all that, you could understand it if Kenneth Avery decided it was finally time to leave New Orleans, maybe move closer to his adult children. But he says that never crossed his mind.

What do you attribute that to?

AVERY: Resiliency – that no matter what happens or no matter what goes on. It’s like backing up a family member. Even though you may know that this family member is not doing the right thing, they’re still family. You can’t change that. And home will always be home.

MARTIN: Here’s councilman Green again.

GREEN: This community is kind of a metaphor for the effects that racism and history have had on our community. The power structure didn’t want Blacks to be in their communities. Honestly. So they said, we’re going to find this large parcel of land and we’re going to build a housing development around it. But unfortunately, because of all of those factors, historically, the property values were not as high as if you were near the lakefront…

MARTIN: Right

GREEN: …Which is where they would have never built a Desire housing project – housing development, for example. And that impacted the people who were here because when it was time to rebuild, the government looked at the value of your property and your community, and it resulted in everyone getting less of an amount of money.

MARTIN: The hurricane and the flooding took so much from so many here. But our visit made clear that for this group of New Orleanians, at least, one thing it could not wash away was their sense of where they belong.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “DO WHATCHA WANNA”)

REBIRTH BRASS BAND: (Singing) Everybody. Everybody be somebody. Be somebody. Everybody. Everybody be somebody. Come on. Whatcha wanna. Whatcha wanna. Do whatcha wanna. Do whatcha wanna. Do whatcha wanna.

Nancy Guthrie search enters its second week as a purported deadline looms

"This is very valuable to us, and we will pay," Savannah Guthrie said in a new video message, seeking to communicate with people who say they're holding her mother.

Immigration courts fast-track hearings for Somali asylum claims

Their lawyers fear the notices are merely the first step toward the removal without due process of Somali asylum applicants in the country.

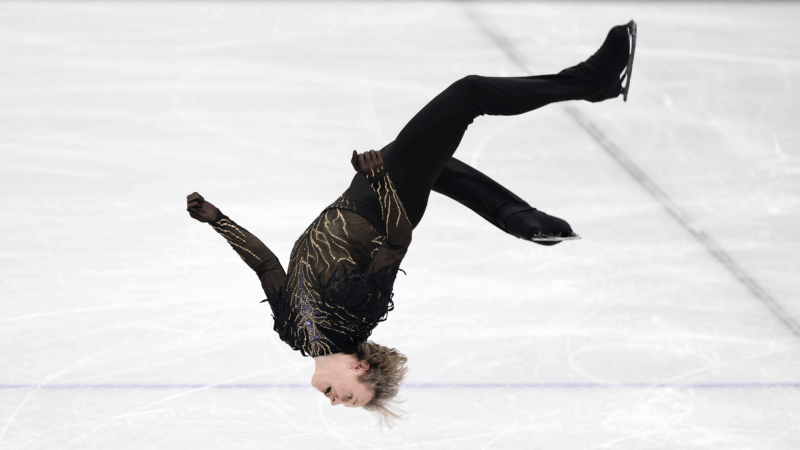

Ilia Malinin’s Olympic backflip made history. But he’s not the first to do it

U.S. figure skating phenom Ilia Malinin did a backflip in his Olympic debut, and another the next day. The controversial move was banned from competition for decades until 2024.

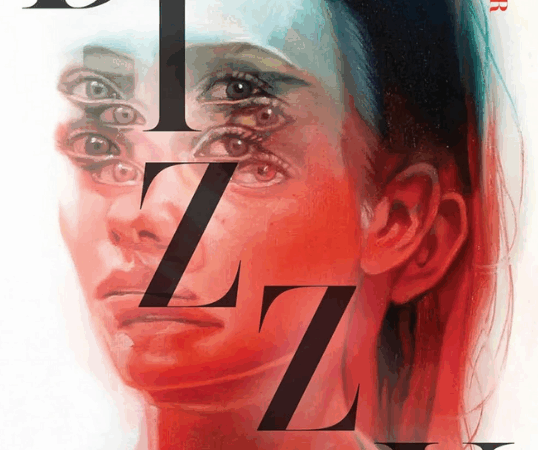

‘Dizzy’ author recounts a decade of being marooned by chronic illness

Rachel Weaver worked for the Forest Service in Alaska where she scaled towering trees to study nature. But in 2006, she woke up and felt like she was being spun in a hurricane. Her memoir is Dizzy.

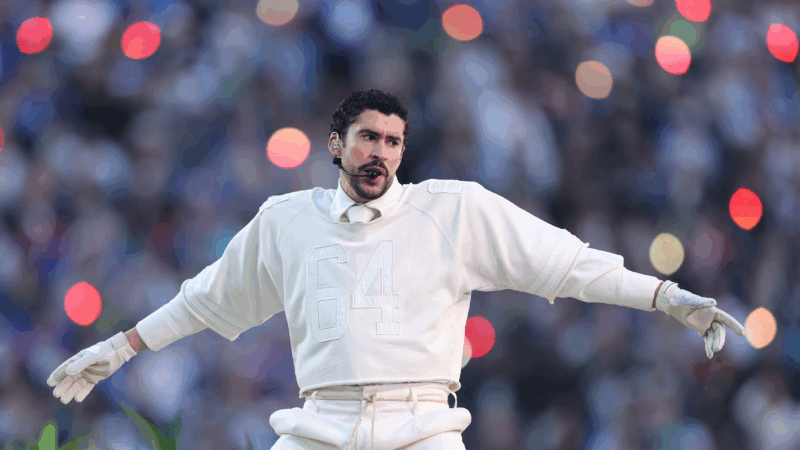

Bad Bunny makes Puerto Rico the home team in a vivid Super Bowl halftime show

The star filled his set with hits and familiar images from home, but also expanded his lens to make an argument about the place of Puerto Rico within a larger American context.

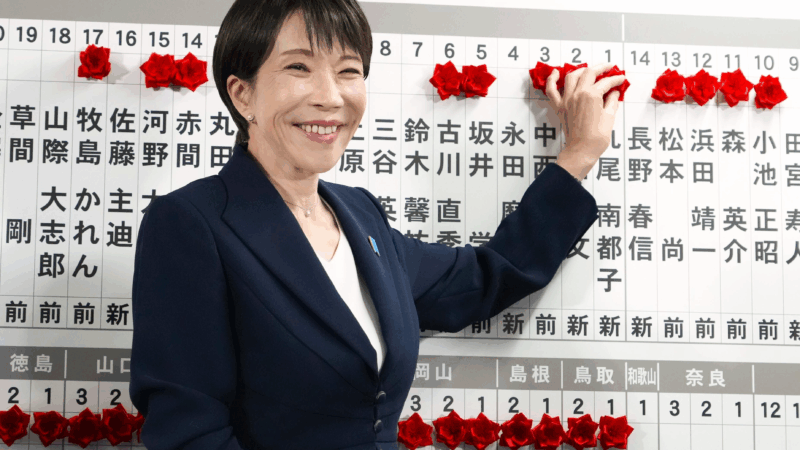

Japan’s Takaichi to pursue conservative agenda after election landslide

Japan's first female Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi, brought the ruling Liberal Democratic Party its biggest-ever electoral victory, fueling her ambitions to pursue to a political agenda which she says could "split public opinion."