In China, AI is no longer optional for some kids. It’s part of the curriculum

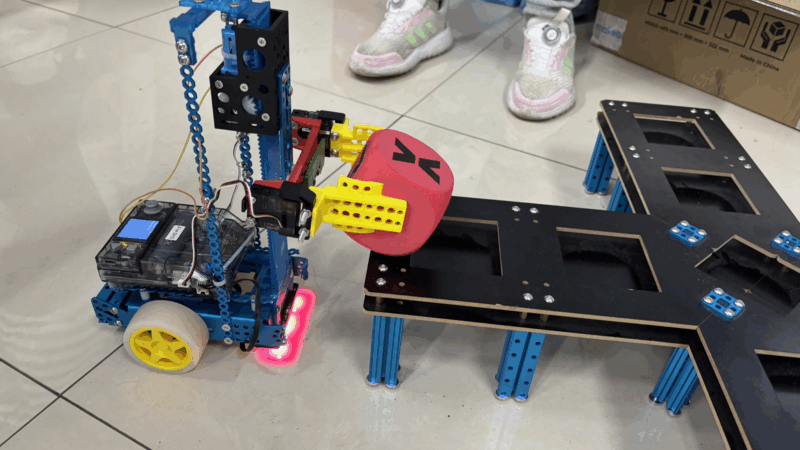

In an elementary school classroom in Beijing’s university district, 11-year-old Li Zichen was demonstrating a small robot. It’s a remote-controlled vehicle that lifts and moves blocks and that can be programmed using artificial intelligence. It’s a small project, but it got him thinking big — about the rovers that China sent to Mars and the Moon.

“If a rover comes across a crater in front of it, for instance, it can’t decide what to do after communicating with Earth,” he says, because sending signals across space takes too long. “It must decide on its own. So I think AI is very important for the nation’s deep space exploration.”

Meanwhile, Li’s classmate, Song Haoyue, has used artificial intelligence as a graphic design tool to help her make a poster for a competition.

“I used Wukong, an AI image software, to create drawings,” she said. She had it render a poster about a mythical bird that tries to fill in the ocean, one pebble at a time — a parable about perseverance.

Debate about artificial intelligence in U.S. schools has simmered for years, with some highlighting the risks of AI in schools — like it stunting cognitive or social development — and others concerned about it exacerbating a growing digital divide.

In China, the authorities have taken a stand.

Wang Le, Zichen and Haoyue’s computer skills teacher at Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications Affiliated Primary School, a public school, said that the Ministry of Education has enacted a new framework. “They require integrating AI courses into the information technology curriculum,” she said.

Starting in the fall, every student in elementary and middle school in Beijing, and several other districts, began learning about AI. Third graders learn the basics. Fourth graders focus on data and coding. By fifth grade, students are learning about “intelligent agents” and algorithms.

It’s about preparing kids for life ahead, Wang said. And another thing: “It’s about enhancing the country’s competitiveness by securing a future pool of skilled professionals.”

“Keji xingguo,” she said. It’s a political slogan that means: “Build a strong nation through science and technology.”

This slogan encapsulates perhaps the ruling Communist Party’s biggest dream: creating a country that is technologically advanced and self-sufficient. AI has been labeled essential for national security and economic competitiveness. The government aims for China to become a global leader in AI within the next four years.

But while the state’s main goal with the AI-in-schools policy is to develop a pool of talent, the parents of the kids — like all parents — are thinking about their children’s futures.

In a tiny, sixth floor walk-up apartment, Li Yutian, Zichen’s father, expressed full-throated support of his child’s interest in robotics and computers. He says he recently took his son to a Xiaomi factory to see what automation looks like in practice. Xiaomi makes some of China’s best-selling cellphones, gadgets and cars.

The two talked on the way home, with the father telling his son Zichen he would need to find work that AI cannot do and differentiate himself to survive. “I said, ‘In the future, if you want mechanical-type work you might, for example, do things like maintenance on robots, or program them and guide them, rather than competing with them,'” he recalled.

Around dinner tables in China, there is debate about some of the same issues Americans are grappling with as kids increasingly use AI: issues like becoming over-reliant on the technology, and stunting their problem-solving skills. Li Yutian thinks China’s tough internet restrictions will help stave off some of the worst risks of AI — like kids getting exposed to violent content.

But sheltering children from this technology is not the way to go, he thinks. “I’ve always believed that not embracing it may be the greatest risk of all,” he said.

Song Zefeng, the father of the girl who made the poster with AI, agrees — for the most part.

“It depends on the level,” he said. “For fifth and sixth grades, at elementary school level, over-exposure is not appropriate.”

Kids this age shouldn’t be online much anyway, he said. But Song thinks having AI be a mandatory part of the curriculum is a smart move.

“The development of AI itself is quite certain, but the biggest uncertainty lies in what society will actually look like in the future,” he said.

He thinks if his daughter can be inspired by what she’s learning in class, maybe she’ll be in a better position to figure out what role she can play in an AI-dominated future — and to weather the coming change.

NPR producer Jasmine Ling contributed to this story.

Families of killed men file first U.S. federal lawsuit over drug boat strikes

The case filed in Massachusetts is the first lawsuit over the strikes to land in a U.S. federal court since the Trump administration launched a campaign to target vessels off the coast of Venezuela.

Has sports betting become part of your daily routine? Tell us about it

It's never been easier to bet on sports. And polls show the majority of American men are involved in sports betting. To learn more, we want to hear from you about your betting experiences.

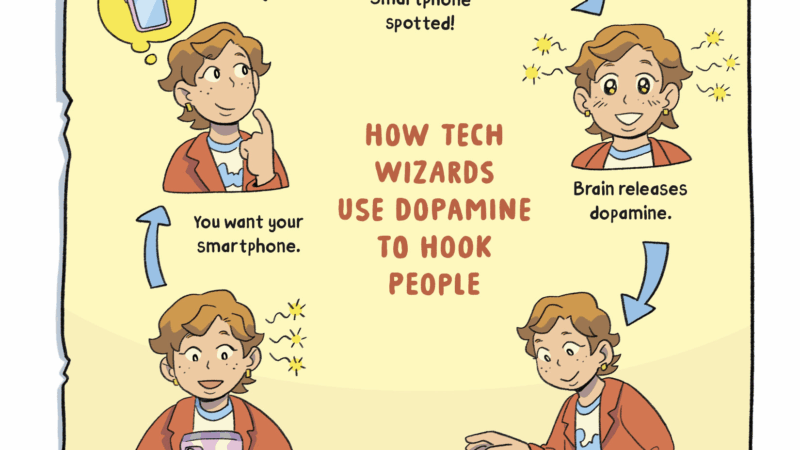

A kids’ guide to phone-free fun, from the author of ‘The Anxious Generation’

Jonathan Haidt's 2024 book made the case that screen time had "rewired" kids' brains. The Amazing Generation is a collab with science journalist Catherine Price and graphic novelist Cynthia Yuan Cheng.

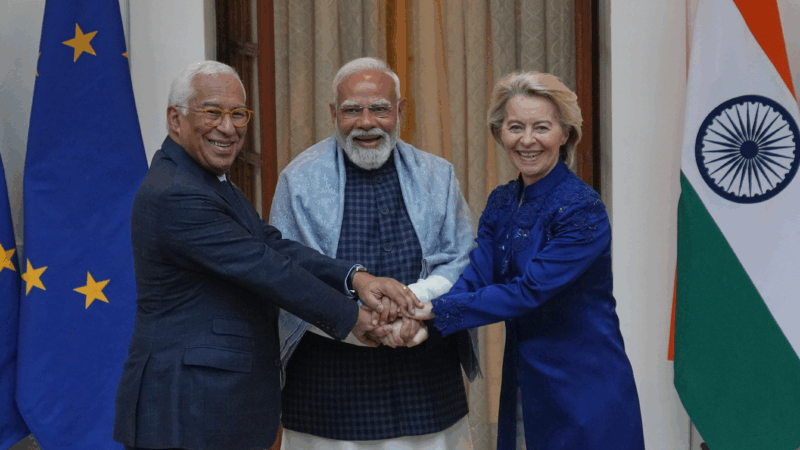

India and the EU clinch the ‘mother of all deals’ in a historic trade agreement

India and the European Union have reached a free trade agreement, at a time when Washington targets them both with steep import tariffs, pushing major economies to seek alternate partnerships.

After rocky start, Bari Weiss to cut staff, add commentators at CBS News

CBS News Editor-in-Chief Bari Weiss came in with a mandate to reshape coverage. She is set to announce plans for newsroom cuts and the hiring of many new commentators.

GLP-1 drugs don’t work for everyone. But personalized obesity care in the future might

As doctors learn why GLP-1s don't work for about 50% of people, they are also learning more about the complex drivers of obesity. They foresee a future of personalized obesity medicine similar to the way cancer is treated now.