If a U.S. ‘bunker buster’ hits a nuclear site, what might get released into the air?

If the U.S. does drop a powerful “bunker buster” bomb on a suspected underground nuclear weapons site in Iran, experts in radiation hazards see little risk of widespread contamination.

The site in question, Iran’s mysterious Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant, is built into a mountainside and seems to be in the business of processing uranium isotopes. That means it would mostly be working with uranium in the form of a gas called uranium hexafluoride.

“It’s a big, heavy gas molecule,” says Emily Caffrey, a health physics expert at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who explains that because this gas molecule is so heavy, “it’s likely not going to travel super-far.”

Any contamination from an attack would remain fairly localized to the site, she says.

While it’s hard to estimate the risks given that the exact type and quantity of the material at the site aren’t publicly known, she says, an environmental release likely wouldn’t present a problem “for anybody that’s not in the immediate area.”

Edwin Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington, D.C., adds that the two major kinds of uranium isotopes found at this type of facility “are at the low end of hazard with regard to radioactive materials.”

“So there’s not a significant, dire health threat if those materials got released to the environment,” he says. “It would probably lead, at most, to a relatively low level of contamination — not zero — but probably fairly close to the site.”

One concern is that uranium hexafluoride gas can react with water in the air to form hydrofluoric acid. “That is an acutely hazardous material that can harm or kill people,” says Lyman.

But in this case, given that the site is in underground caverns “and the bunker busters are designed to collapse the mountain above it,” he says, “any kind of environmental release would be relatively low since it would be essentially inhibited by this mass of rock that’s rained down on it.”

Rafael Mariano Grossi, the director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, has said that the agency has been monitoring the effects of strikes on Iran’s facilities.

One attack damaged the aboveground portion of the Natanz Fuel Enrichment Plant, he recently reported, but the “level of radioactivity outside the Natanz site has remained unchanged and at normal levels, indicating no external radiological impact to the population or the environment from this event.”

Inside the site, however, he said there was “both radiological and chemical contamination,” with the main concern being the chemical toxicity of uranium hexafluoride and the compounds generated when it made contact with water.

The main radiation danger there would come from inhaling or ingesting uranium, he said, but “this risk can be effectively managed with appropriate protective measures, such as using respiratory protection devices while inside the affected facilities.”

Swiss Alpine bar fire claims 41st victim, an 18-year-old Swiss national

Swiss prosecutors have opened a criminal investigation into the owners of Le Constellation bar in the ski resort of Crans-Montana, where a fire in the early hours of Jan. 1 killed dozens.

Sunday Puzzle: Rhyme Time

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with WBUR listener Laurie Rose and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

Alcaraz beats Djokovic to become the youngest man to complete a career Grand Slam

The 22-year-old Spaniard's win against 38-year-old rival Novak Djokovic at Sunday's Australian Open makes him the youngest male player to win all four major tournaments.

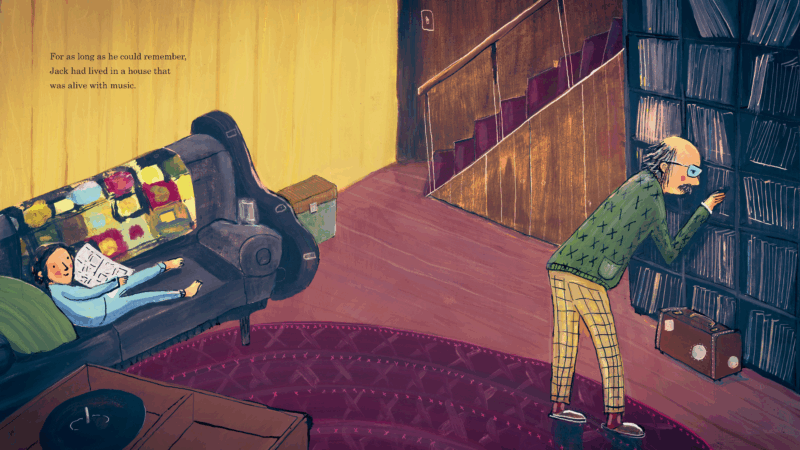

You already know the song — now, ‘The One About the Blackbird’ is also a picture book

In The One About the Blackbird, a young boy learns to play guitar from his grandfather. And there's one song in particular that they love…

In the world’s driest desert, Chile freezes its future to protect plants

Tucked away in a remote desert town, a hidden vault safeguards Chile's most precious natural treasures. From long-forgotten flowers to endangered crops.

At a clown school near Paris, failure is the lesson

For decades, students at the Ecole Philippe Gaulier have been paying to bomb onstage. The goal isn't laughs — it's learning how to take the humiliation and keep going.