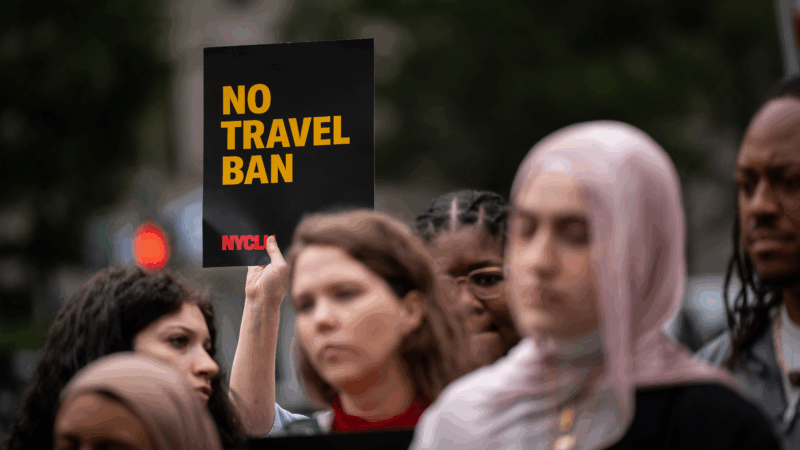

How Trump’s travel ban could disrupt the way knowledge about health is shared

Abdul-Rahman Edward Koroma was supposed to be in New York last week.

For months, the disability rights activist from Sierra Leone had been looking forward to his trip to the United Nations session. He had a busy schedule of meetings and official events talking about the challenges of living with a disability in his country, including showcasing a documentary about how the disability community is especially vulnerable to flooding and landslides associated with climate change.

But on June 5, he learned he couldn’t come. Sierra Leone was one of 19 countries where President Trump had banned or restricted the ability to travel to the U.S.

“Honestly, for me, it’s quite painful, and it’s quite disappointing,” says Koroma. “I hope the U.S. government will reconsider. The world is a global village, we all need each other, one way or the other.”

Why is Sierra Leone on the list? The Trump administration cites high levels of visitors to the U.S. who’ve overstayed their visa as the reason. Other countries were selected for national security reasons.

“We will restore the travel ban, some people call it the Trump travel ban, and keep the radical Islamic terrorists out of our country that was upheld by the Supreme Court,” President Trump said in a statement.

The administration banned travelers from Afghanistan, Myanmar, Chad, the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen. Travelers from Burundi, Cuba, Laos, Sierra Leone, Togo, Turkmenistan and Venezuela also face some restrictions.

More bans may be coming. A State Department memo first reported by the Washington Post and confirmed by NPR suggests the administration may add 36 more countries, largely in Africa, to the banned or restricted list.

Consequences of the ban

Stories like Koroma’s will likely accumulate over the coming weeks and months, as global health researchers, workers and advocates from these countries are barred from coming to the U.S. to learn — and to share their expertise. Some global health specialists say the restrictions will ultimately harm U.S. interests by reducing our engagement with the world.

“We are closing ourselves off from the active participation of potential allies,” says Judd Walson, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University. “That will only lead to negative consequences in the long term.”

Closing the U.S. off could ultimately open it up more to global health threats, says Walson.

The ban follows the administration’s cancellation of foreign aid and withdrawal of U.S. membership from the World Health Organization. Walson says these decisions are upending many of the institutions designed to detect and respond to disease threats worldwide.

“As we think about the new architecture of global health and how it can respond to the many crises that emerge around the world, participation from all these countries is critical,” says Walson, and ultimately benefits Americans.

He notes that new infectious disease threats could emerge from any of the banned countries.

“Our inability to engage with partners from those places, who can serve as eyes and ears on the ground to identify threats. just hampers our ability to have a coordinated response,”

Abraar Karan, an infectious disease physician at Stanford University, is concerned future bans could hamper his team’s research on Marburg, a hemorrhagic fever virus. It’s normally found in bats, but can spillover into humans, sparking deadly outbreaks.

Karan and his team are trying to understand those spillover dynamics, in part by studying antibodies in people who live near past outbreaks along the Uganda-Kenya border.

“Part of the testing we’d do involves a test where there’s expertise in Uganda, at the Ugandan Viral Research Institute,” says Karan.

Uganda is among the 36 countries under consideration for future restrictions. If that happens, Karan worries his team may have restricted access to that expertise. While such restrictions wouldn’t preclude collaboration via Zoom, Karan says it’s just not the same as in-person.

“Many of the best conversations and ideas that we had happened during our drives, during meals or unplanned moments,” he says of interactions with foreign researchers in person. “Implementing these kinds of bans has a huge effect on research studies and really impedes progress.”

Scientific conferences often serve as the nexus for that kind of collaboration, where researchers gather to share research and connect with colleagues. Trump’s travel restrictions are already preventing some scientists from being able to travel to the U.S. for conferences.

“We need to have such participation and contact, but it’s now very difficult,” said a biomedical scientist from Yemen who requested anonymity because speaking out could draw negative attention that would cause her university to retaliate. The scientist was planning to travel to California this fall for a conference on cancer management but cannot because of the ban, noting:. “Such an absolute restriction for all people is not wise.”

The U.S. could also lose its global role as a key location for trainings and scientific conferences. The travel bans, coupled with broader tensions around immigration in the U.S., have already led organizers of these events to look elsewhere.

“Our research team decided to host a planning meeting in London as opposed to the U.S. due to concerns with visas and the overall climate,” says Walson. There are economic consequences if U.S. conferences are canceled, he says. And with a likely reduced U.S. presence at conferences held elsewhere, there could be more intangible impacts too.

“Diseases don’t respect borders, and infections travel faster than diplomacy,” says Walson. “Whether we want to or not, we have to understand the reality of the global community as it is today. If we don’t engage, we will suffer the consequences.”

Team USA faces tough Canadian squad in Olympic gold medal hockey game

In the first Olympics with stars of the NHL competing in over a decade, a talent-packed Team USA faces a tough test against Canada.

PHOTOS: Your car has a lot to say about who you are

Photographer Martin Roemer visited 22 countries — from the U.S. to Senegal to India — to show how our identities are connected to our mode of transportation.

Looking for life purpose? Start with building social ties

Research shows that having a sense of purpose can lower stress levels and boost our mental health. Finding meaning may not have to be an ambitious project.

Sunday Puzzle: TransformeR

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with listener Joan Suits and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

Danish military evacuates US submariner who needed urgent medical care off Greenland

Denmark's military says its arctic command forces evacuated a crew member of a U.S. submarine off the coast of Greenland for urgent medical treatment.

Only a fraction of House seats are competitive. Redistricting is driving that lower

Primary voters in a small number of districts play an outsized role in deciding who wins Congress. The Trump-initiated mid-decade redistricting is driving that number of competitive seats even lower.