How Trump’s cuts to U.S. foreign aid are imperiling Syria’s war crimes investigations

DAMASCUS, Syria — Omar Halaby hobbles through the ruins of his old neighborhood on one leg, with a crutch.

A freckled former teen fighter, Halaby lost his right leg in a 2017 air and artillery attack by Syrian forces loyal to then-President Bashar al-Assad. With Assad’s ouster in December, Halaby, now 29, returned to his neighborhood of Jobar, on the edge of Damascus, to watch a backhoe unearth the remains of at least eight of his comrades from a mass grave.

“The regime has fallen, and I need to transition to civilian life,” Halaby says. “Part of that process is seeing my late friends one last time, to give them a dignified reburial.”

Jobar elders first called the White Helmets, wartime Nobel Peace Prize nominees who are Syria’s most skilled first responders. But the group is overstretched, having lost its U.S. funding, and its dispatcher told Jobar residents they would have to get on a waitlist for help excavating mass graves.

So, with Halaby and others watching, neighbors decide to do it themselves — with a backhoe provided by a local civil engineer.

But an argument breaks out between the medical examiner, paramedics from the Syrian Red Crescent and municipal officials about what procedures need to be followed. Unexploded ordnance litters the area, some neighbors warn. The backhoe remains unused.

Syria’s longtime dictator is gone. A nearly 14-year civil war is over. But more than 130,000 people remain missing. And the fledgling new state needs help clearing mines, unearthing mass graves and collecting evidence for war crimes investigations.

Jobar’s stalled effort reflects some of the larger obstacles facing Syria as it tries to uncover and seek justice for past atrocities, even as support is being cut.

“This is only the start of transitional justice in Syria, and the job is enormous,” says Stephen Rapp, former U.S. ambassador-at-large for war crimes, who visited Syria in February. “Syria needs reliable partners to obtain DNA samples from survivors through swabs of saliva, then begin this long process of excavating mass graves.”

But many of the groups with expertise in these things rely on funding from the United States — and, like the White Helmets, have recently lost it. They’re asking the Trump administration not to renew a 90-day pause on foreign aid, which expires this month.

Cuts to U.S. aid hurt White Helmets

Vilified by Assad as terrorists, the White Helmets — a nonprofit volunteer first responder group named for the color of their headgear — used to operate only in rebel-held areas. There, throughout the Syrian civil war, they were celebrated for running into danger to aid civilians. A 2016 documentary about them won an Oscar.

Within days of Assad’s Dec. 8 ouster, they entered the Syrian capital and set up new headquarters in a central Damascus fire station. Their founder Raed Saleh has since been named to Syria’s Cabinet. And his roughly 3,300-member team is struggling to extend its services to the entire country, becoming Syria’s main civil defense force.

“Most of Syria is destroyed, and our teams are overstretched everywhere,” says Farouq Habib, the group’s deputy. “We have documented more than 50 mass graves, and we need resources.”

But just as their mission is expanding, their biggest contributor up to now — the U.S. Agency for International Development — has pulled funding. When the Trump administration dismantled USAID, calling it rife with waste and fraud, the White Helmets lost a $30 million contract — more than half of which was already spent. The group has an annual budget of about $50 million.

“This hinders our survival,” Habib says, sighing.

The White Helmets still have two forensics teams supported by a much smaller U.S. State Department grant worth about $2.5 million, he notes. That funding was cut, then reinstated, this year.

Despite the Trump administration’s cuts, private U.S. citizens are generous and the group is deeply appreciative, Habib says. Almost one-third of the group’s global donations come from Americans, he says. The rest of the White Helmets’ funding comes from foreign aid donations from other governments and individuals including in Britain, Germany, Denmark and Canada, Habib says.

The process of gathering evidence for possible war crimes trials has slowed

When Assad fell, the doors of Syria’s prisons and government offices swung open. Government archives were looted; documents littered the streets. Human rights investigators rushed to collect those documents and preserve them as evidence for possible future trials. But they need help sorting through what they have.

“We have thousands and thousands of documents, with lots of details that could help families reveal the fate of their loved ones,” says Fadel Abdulghany, executive director of the Syrian Network for Human Rights. “Because those documents often contain the names of those who were arrested [under Assad], the date of when they were killed or moved to a grave — and even the names of the perpetrators as well.”

Abdulghany budgeted to hire a new researcher this year, dedicated to those documents. After operating from the United Kingdom and Qatar during Syria’s civil war, he’d also been looking forward to opening a new office in Damascus.

But his organization’s USAID funding was cut too, hindering both of those things.

“All of our activities have been limited, including testimonies we’ve been taking from people released from Assad’s prisons,” Abdulghany says. “The U.S. used to be a reliable partner. But the mentality of how U.S. soft power is used around the world is changing.”

It’s not just Syria. The Trump administration has cut aid that funded schools, vaccination programs, medication and medical equipment, media organizations and literacy programs around the world. Trump has said he wants overseas spending to more closely align with his foreign policy goals and “America First” approach.

Syrian survivors say their pain is prolonged

Majida Kaddo, 60, stands at night in a Damascus traffic circle with a candle, shoulder to shoulder with other survivors, receiving condolences from passersby and friends.

Kaddo has five relatives who disappeared into Assad’s prisons during the civil war. None was ever charged with a crime. Only one of their bodies was found.

On Dec. 8, when Assad fled, she rushed — along with thousands of other Syrians — to Damascus’ notorious Sednaya prison, searching for her relatives’ faces in the crowds of freed prisoners stumbling out. They never emerged.

Kaddo hopes human rights investigators combing through evidence might eventually find answers for her family. But she’s devastated by news their work has been hobbled by U.S. aid cuts.

“There’s nothing worse than being so close to justice, after 14 years of war,” she says. “And then to have your pain prolonged.”

NPR producer Jawad Rizkallah contributed to this report from Damascus.

Transcript:

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

Syria’s dictator is gone, but more than a hundred and thirty thousand people are still missing. And some of the groups helping Syrian families find answers are dealing with the Trump administration’s foreign aid freeze. NPR’s Lauren Frayer has more from Damascus.

(SOUNDBITE OF FOOTSTEPS IN RUBBLE)

LAUREN FRAYER, BYLINE: This used to be your…

MOHAMED ALI: Yeah.

FRAYER: …Neighborhood?

ALI: It’s my building.

FRAYER: This pile of…

ALI: Yes.

FRAYER: …Of rubble.

Mohamed Ali (ph) stands in the ruins of Jobar, a Damascus neighborhood famous for a historic synagogue and for some of the bloodiest battles of the Syrian civil war.

ALI: In every building, there’s a grave. Our family, our friends, our people died here, here, here.

FRAYER: He points to mass graves all around him when the civil war ended late last year.

ALI: We (vocalizing) life again.

FRAYER: Ali hoped to give his dead relatives and friends a proper reburial. He’s a civil engineer, and he’s brought a backhoe to unearth these mass graves, but an argument breaks out between the medical examiner and government officials about what procedures need to be followed. Syria needs help with stuff like this – unearthing mass graves, collecting evidence for war crimes investigations. But many of the groups with expertise in this rely on U.S. funding and have recently lost it.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: So when Jobar residents called for help from The White Helmets, Syrian first responders who’ve been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, they got put on a waitlist.

FAROUQ HABIB: We are overstretched. We’re dealing with numerous mass graves, and we need resources.

FRAYER: The White Helmets deputy leader, Farouq Habib, says the U.S. Agency for International Development was his group’s biggest funder. And when the Trump administration dismantled USAID, calling it rife with waste and fraud, The White Helmets lost a $30 million contract out of its $50 million annual budget.

HABIB: Well, it hinders our survival.

FRAYER: When dictator Bashar al-Assad fled, Syrian prisons sprung open. Government archives littered the streets. One of the people collecting those documents as evidence for possible trials in the future is Fadel Abdulghany.

FADEL ABDULGHANY: We have thousands of thousands of documents, the names of those arrested, and the date of when those being killed or being moved to a grave, and the name of the perpetrators, as well.

FRAYER: Abdulghany runs the Syrian Network for Human Rights, which also lost U.S. funding this year and thus won’t be able to open a new office in Damascus or hire a new researcher to go through all these documents. This is happening at the very moment this work needs to ramp up, says Stephen Rapp, a former U.S. ambassador-at-large for war crimes, who visited Syria in February.

STEPHEN RAPP: Everybody I talked to in Syria at every detention facility or at the courtroom in Homs, where, you know, a hundred people are crammed in the hallways with pictures of their loved ones demanding action. They want that information. Of course, we also need to begin the process of obtaining DNA samples from survivors through swabs of saliva and then beginning this long process of excavating the mass graves.

FRAYER: The mass grave in Jobar, nevertheless, remains untouched. The White Helmets and others are asking the Trump administration not to renew a 90-day pause on U.S. foreign aid that expires this month and help people like Majida Kaddo (ph), who stands in a Damascus traffic circle with a candle receiving condolences. Kaddo has five relatives who were disappeared by the Assad regime. Only one of their bodies has been found.

MAJIDA KADDO: (Speaking Arabic).

FRAYER: “There’s nothing worse,” she says, “to be so close to justice after 14 years of war and then to have your pain prolonged.”

Lauren Frayer, NPR News, Damascus.

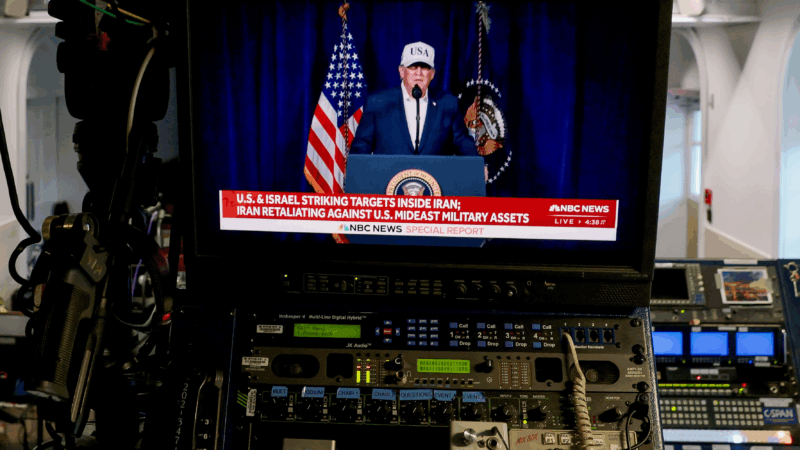

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.

Political science expert weighs in on Iran’s nuclear program in light of U.S. strikes

NPR's Scott Simon speaks to Ariane Tabatabai, the Public Service Fellow at Lawfare, about U.S. attacks on Iran and how President Trump's calls for regime change might be received there.

Week in Politics: Does Trump have political support for his actions in Iran?

We look at what President Trump's decision to attack Iran means, what kind of support he has in Iran and what this moment means for his administration.