How migrating Australian moths find caves hundreds of miles away

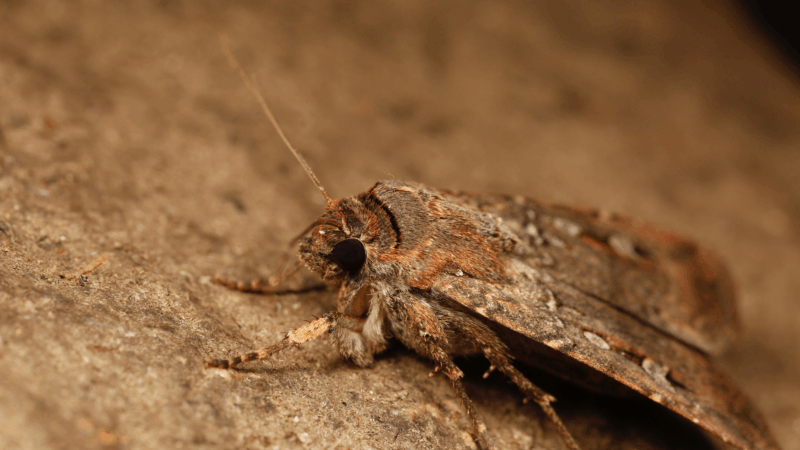

The Bogong moths of Australia aren’t much to look at, says Andrea Adden, a neurobiologist at the Francis Crick Institute. “They’re small brown moths with arrow-like markings on the wings. They’re pretty nondescript.”

But these insects undertake an epic migration twice in their lifetime, traveling hundreds of miles in each direction.

Researchers have shown that the Earth’s magnetic field helps the moths orient, but that alone wasn’t sufficient. “They needed something visual to go with it,” says Adden.

She wanted to know what that cue might be over such a vast landscape — especially at night when there’s little light.

In a paper published in the journal Nature, Adden and her colleagues show that the cue comes from the heavens. That is, the starry sky allows the Bogong moths to both orient and navigate.

“It’s the first time that we have found an invertebrate using the stars to navigate,” says Adden. “And also the first time that anyone had seen neurons that specifically respond to the starry sky in the insect brain.”

A 600-mile winged migration

Bogong moths follow an annual rhythm.

They hatch in their breeding grounds in the spring in southeast Australia where it gets really hot in the summertime. “So if they were to reproduce immediately, their larvae would starve because there is not enough food,” says Adden.

Instead, the moths migrate over multiple nights more than 600 miles south to the Australian Alps where they settle in cooler caves, entering into a dormant phase called estivation (like hibernation but in the summer), by the millions.

“It’s just moth over moth over moth,” says Adden. “You don’t see any cave wall anymore. It’s just moths.”

In the fall, they return to their breeding grounds, mate, lay their eggs, and die.

“Then the next year, the new moths hatch,” says Adden. “And they’ve never been to the mountains. They have no parents who can tell them how to get there.”

And yet they make it.

She suspected the stars might offer just the cue they need. “The Milky Way is such a stunning sight,” she says. “And it seemed an obvious thing to use if you are a moth living in that environment.”

A planetarium show in miniature

To test her theory, Adden, who was doing her Ph.D. at Lund University in Sweden at the time, and her colleagues caught moths in the Australian Alps and ran them through one of two experiments in the dead of night.

The first was a behavioral test. It involved placing a moth inside what was basically a mini-planetarium that contained a projection of the night sky and no magnetic field.

“It’s not an experiment that always works,” says Adden. “We’re reliant on the moths cooperating with us.” Fortunately, enough moths did cooperate. And the result surprised the researchers.

“They didn’t just circle and do twists and turns, but they actually chose a fairly stable direction,” she said. “Not only that, it was their migratory direction.”

In other words, the moths were using the starry sky as a compass cue to orient and navigate.

Adden’s next question involved what was happening in the moth’s brain. She recorded the electrical activity of individual neurons while rotating a projection of the Milky Way.

When she looked in the brain regions that process visual information, the majority of neurons were active when the moth was facing south. This specific direction suggests that the moths’ brains encode direction by processing visual cues of the Milky Way.

Beyond the moth

Biologist Pauline Fleischmann at the University of Oldenburg studies navigation in desert ants in Greece and says she’s fascinated by the study.

“It shows that insects, their world is probably much more filled with information than humans usually assume,” she says.

In addition, the moths’ ability to use both visual and magnetic information to navigate can be essential for survival — in case it’s cloudy, say, or the magnetic field is unreliable. “If one fails, they have a backup system,” says Fleischmann.

The Bogong moths are endangered. Adden says her findings could help conserve these insects — and everything that relies on them for food. As a first step, reducing light pollution would help these moths continue their star-led journey across the Australian bush.

“Protecting the Bogong moth would help us protect the entire Alpine ecosystem,” she says.

Farmers are about to pay a lot more for health insurance

Tariffs, inflation, and other federal policies have battered U.S. farmers' bottom lines. Now many farmers say the expiration of federal health care subsidies will make their coverage unaffordable.

Why do we make New Year’s resolutions? A brief history of a long tradition

One of the earliest mentions of New Year's resolutions appeared in a Boston newspaper in 1813. But the practice itself can be traced back to the Babylonians.

In one year, Trump pivots fentanyl response from public health to drug war

Experts say Biden's focus on addiction health care saved tens of thousands of lives and slowed fentanyl smuggling. Trump scrapped Biden's approach in favor of military strikes.

Judge orders new trial for Alabama woman sentenced to 18 years in prison after stillbirth

Lee County Circuit Judge Jeffrey Tickal vacated Brooke Shoemaker’s 2020 conviction for chemical endangerment of a child resulting in death. Tickal said Shoemaker's attorneys presented credible new evidence that the infection caused the stillbirth.

Remembering the actors, musicians, writers and artists we lost in 2025

Every year, we remember some of the writers, actors, musicians, filmmakers and performers who died over the past year, and whose lifetime of creative work helped shape our world.

A little boy gave her hope for her foster daughter’s future

At a neighborhood park, a young boy noticed Natalie's young foster daughter using a walker. His reaction left Natalie with an unexpected feeling of hope for the future.