How land-loving iguanas from North America may have ended up in Fiji

Fijian iguanas pose a conundrum to biologists: How did these lizards normally found in the Americas wind up thousands of miles away on an isolated tropical island in the South Pacific?

By floating on a raft of downed trees and broken branches, according to a study published Monday in the journal PNAS. The voyage made by these inadvertently intrepid iguanas would represent the longest transoceanic migration of any nonhuman land vertebrate.

“We often forget how vast the Pacific Ocean is,” says Mozes Blom, a biologist at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin who wasn’t involved in the study. “But it’s really when flying across the Pacific, and not seeing anything but ocean for hours, that it dawns how unique it is that some animals manage to disperse across it.”

Biologists have long disagreed over how iguanas got to Fiji. While some supported the raft idea, others argued that such a long journey was too far-fetched. Instead, iguanas could have traveled there more gradually, island-hopping and walking across ancient land bridges to populate parts of Asia and the Pacific before dying out everywhere except Fiji.

But there wasn’t enough evidence to distinguish between these possibilities, said Simon Scarpetta, an evolutionary biologist at the University of San Francisco. “Part of the problem was that we didn’t really know how the Fijian iguanas were related to other iguanas. And we didn’t really know how old they were.”

To find that out, he and his colleagues used genomic data from 14 different species to build an iguana family tree and estimate when Fijian iguanas diverged from their cousins. The results surprised Scarpetta.

“The iguanas that live on Fiji were most closely related to a group of iguanas that I knew very well from the United States called desert iguanas,” he says.

The team estimates that those two groups split about 34 million years ago, a timeline that doesn’t quite add up with the land-bridge idea, as clear routes from the Americas via the Bering Strait or Antarctica would have been mostly underwater by then. They argue that a single dispersal event, likely more than 5,000 miles, from North America to Fiji is the most likely scenario.

The study “does an excellent job cracking such a tough phylogenetic question,” says Blom. He generally buys their argument, though he cautions that alternatives can’t be completely ruled out because “these scenarios played out over such a long timescale.”

Scientists have observed iguanas making similar, albeit shorter, trips in the Caribbean. In the mid-’90s, researchers actually tracked a group of about 15 iguanas hitching a ride on a tangle of downed trees after a hurricane. The iguanas safely made it from Guadeloupe to Anguilla, Scarpetta said, a distance of about 186 miles.

Reaching Fiji would have been nearly 30 times as far. But if any creature could make such a journey, it’s iguanas, said Scarpetta.

“They’re large, so they have a good amount of body mass to sustain them,” said Scarpetta. “And they’re herbivorous, so if they’re floating around on vegetation, they may even have a source of food to eat.”

Given their desert ancestry, these iguanas would’ve been ideally suited to withstand the dehydration and intense sun of such a long journey.

Even with those advantages, surviving such a journey still defies belief. But this analysis suggests that from the perspective of evolutionary timescales, Blom said, “it may not be that improbable.”

Transcript:

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

Here’s a reptilian mystery millions of years in the making. How did land-loving iguanas normally found in the Americas wind up thousands of miles away in the South Pacific in Fiji? NPR’s Jonathan Lambert has more on some possible answers.

JONATHAN LAMBERT, BYLINE: Scientists have two major theories to explain how iguanas ended up on the tropical island Fiji. Simon Scarpetta is a biologist at the University of San Francisco.

SIMON SCARPETTA: People had suggested that they must have taken some kind of raft of down vegetation from somewhere in the Americas all the way across the Pacific, you know, through the doldrums of the equator, through the southern equatorial current, and then made their way to Fiji.

LAMBERT: The other idea is that Fiji and Iguanas got there much more gradually. Over many generations, iguanas from the Americas might have walked or island-hopped over land bridges that are now underwater. But biologists haven’t had enough evidence to distinguish between these possibilities.

SCARPETTA: We didn’t really know how the Fijian iguanas were related to other iguanas, and then we also didn’t really know how old they were.

LAMBERT: To figure that out, Scarpetta and his colleagues used genomic data to build a detailed family tree. The results published in the journal PNAS surprised him.

SCARPETTA: The iguanas that live on Fiji were most closely related to a group of iguanas that I knew very well from the United States called desert iguanas.

LAMBERT: Scarpetta estimates that these iguanas split a little over 30 million years ago, a timeline that doesn’t quite line up with the land bridge idea. Instead, he thinks a small group of iguanas made one single trip from North America to Fiji. Similar albeit shorter trips have been observed on tangles of downed trees in the Caribbean.

SCARPETTA: People saw in real time that green iguanas were able to get around 300 kilometers just floating on displaced vegetation from one island to the other, and so that was super cool.

LAMBERT: Reaching Fiji would have been nearly 30 times as far, but if any creature could survive, it’s iguanas.

SCARPETTA: They’re herbivorous, and so if they’re floating around on vegetation, they may even have a source of food to eat.

LAMBERT: And with desert origins, these iguanas could have survived dehydration in the intense equatorial sun as they slowly drifted towards their new home.

Jonathan Lambert, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF PORTLAND CELLO PROJECT’S “PITSELEH”)

Italian fashion designer Valentino dies at 93

Garavani built one of the most recognizable luxury brands in the world. His clients included royalty, Hollywood stars, and first ladies.

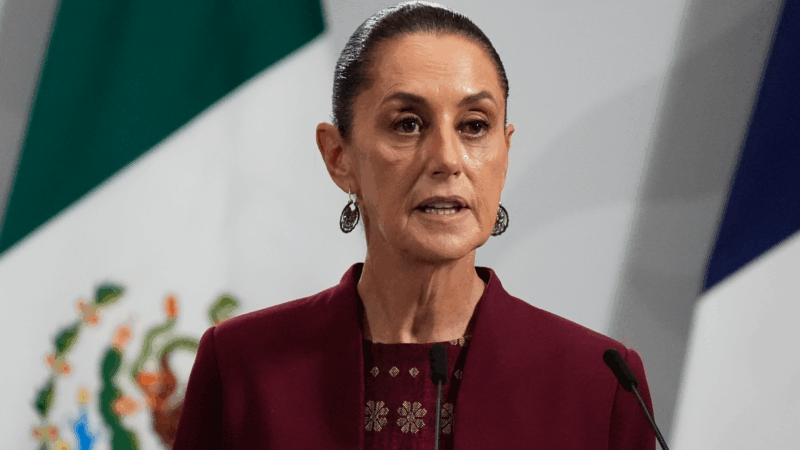

Sheinbaum reassures Mexico after US military movements spark concern

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum quelled concerns on Monday about two recent movements of the U.S. military in the vicinity of Mexico that have the country on edge since the attack on Venezuela.

Trump says he’s pursuing Greenland after perceived Nobel Peace Prize snub

"Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize… I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace," Trump wrote in a message to the Norwegian Prime Minister.

Trump has rolled out many of the Project 2025 policies he once claimed ignorance about

Some of the 2025 policies that have been implemented include cracking down on immigration and dismantling the Department of Education.

U.S. lawmakers wrap reassurance tour in Denmark as tensions around Greenland grow

A bipartisan congressional delegation traveled to Denmark to try to deescalate rising tensions. Just as they were finishing, President Trump announced new tariffs on the country until it agrees to his plan of acquiring Greenland.

Can exercise and anti-inflammatories fend off aging? A study aims to find out

New research is underway to test whether a combination of high-intensity interval training and generic medicines can slow down aging and fend off age-related diseases. Here's how it might work.