How do ‘torpedo bats’ work? We asked baseball physicists to explain

If you were making a bowling pin on a lathe and suddenly decided to make a baseball bat instead, the result would look something like the “torpedo bat” that is the talk of MLB’s new season. After some New York Yankees used the unusual bats to launch a barrage of home runs on opening weekend, scientists who study baseball quickly took notice.

“The same bat design has been in existence for a century and a half, maybe,” says Alan Nathan, professor emeritus of physics at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “And to come up with something new, to me, is always very exciting.”

Nathan and other experts say they’re fascinated that the hype is over the shape of a hunk of wood, one that even baseball’s rulebook calls a “stick.”

“There’s just not a whole lot you can do with this stuff,” Lloyd Smith, a professor of mechanical engineering at Washington State University, tells NPR. He says he usually finds wood a bit boring — but he adds that in this case, “I was proven wrong.”

The logic behind the torpedo bats seems deceptively simple: Their bulbous shape comes from analyzing how hitters tend to make contact with the ball.

“If they’re making contact at the same place in the barrel all the time, what can we do about the bat to try and give them better performance at that specific location?” says Dan Russell, an acoustics professor at Penn State University.

Russell, Smith, and Nathan weren’t involved in designing the new bats. But they have a long history of studying how baseball works, including a collaboration studying illegal “corked” bats.

The torpedo bats are legal, conforming to MLB’s rule 3.02, which states, “The bat shall be a smooth, round stick not more than 2.61 inches in diameter at the thickest part and not more than 42 inches in length.”

As for weight, Babe Ruth famously used bats weighing more than 40 ounces — but the current norm is around 31 or 32 ounces, similar to the 33 ounces wielded by Hank Aaron, according to the Louisville Slugger Museum.

Torpedo bat designs can reduce weight, a crucial component as batters face pitchers throwing baseballs faster than ever. So, why hasn’t anyone tried the approach before in baseball — a sport famous for its obsession with metrics?

“The guy who had the idea, of course, has a physics background,” Nathan says. “So that’s why I am, in a way, I’m jealous.”

The guy in question is Aaron Leanhardt, a former MIT physicist who became a Yankees analyst and now works for the Miami Marlins. He’s credited with driving the new design.

Torpedo bats broke an ‘unwritten rule’ in design

For a sense of how a torpedo shape might help a batter, consider modern “cupped” bats, their barrels ending with a deep indentation rather than a rounded curve.

“That’s important weight” to eliminate, Smith says. “That’s at the end of the bat — that’s going to be much more important than weight near the handle. It makes the bat a little easier to swing.”

“You want to remove the weight where it doesn’t do you any good,” Nathan says. “Now the next logical step is not only to remove weight but move it somewhere else. So that is the next logical step.”

To take that step, the torpedo designers broke what Smith calls an unwritten rule: For decades, a bat’s diameter basically increased from the handle to the barrel, never decreasing until rounding off at the end.

Torpedo bats’ diameters widen, but then they narrow, bringing a number of dynamics into play. On an essential level, Nathan says, moving weight from the end of the bat closer to the hands reduces “what’s called the swing weight or in technical language, the moment of inertia of the bat, making it easier to swing, easier to control.”

Another potential benefit, he adds, is if the design allows a bat to have a slightly wider diameter in a batter’s favored location without adding to the swing weight.

“Then the advantage is having a larger surface over which to make contact with the ball,” he says.

But the torpedo design doesn’t necessarily translate to more power at the plate.

“If you lower the swing weight, you increase your swing speed,” which is “super important for batted ball speed” and hitting the ball farther, Smith says. The tradeoff, he adds, is that by lowering a bat’s swing weight, “you swing the bat faster, but you have less mass to hit the ball with.”

To picture how that works, we should visualize a sledgehammer, according to Scott Drake, president of PFS-TECO, a wood products company that inspects bats used in the MLB.

“If you could swing a sledgehammer really fast and make contact with the ball right at the head, it’s going to go really far,” Drake says. Of course, it would be difficult to swing a sledgehammer with that much speed and accuracy.

If you slide the weight down the handle toward your hands, he says, it becomes easier and easier to swing faster — “but when you make contact on the end, there’s less and less mass for where you make contact.”

“For the average person, what it means is if you lower the swing weight of a bat, your batted ball speed goes down a little bit,” Smith says.

Of course, major league hitters are not average people. But it’s worth noting that of the Yankees’ nine home runs last Saturday, three were hit by Aaron Judge — using his normal, non-torpedo bat.

Russell, Smith and Nathan say they’re eager to conduct tests on the new bats to see how they balance those competing factors — and how the design affects a bat’s “sweet spot,” where the collision of bat and ball is most efficient.

So, do the bats give hitters an edge?

“I don’t think it’s hitting the ball any faster,” Russell says of the torpedo bat. But, along with the potential gains in bat control, he and his colleagues believe the bats might boost a less measurable factor: batters’ confidence.

“The game of baseball is so superstitious,” Russell says. “It doesn’t matter what the thing is, if you found something that makes you more confident, it’s going to work.”

That dynamic extends from the batter’s box out to the mound, where pitchers are likely to see more batters holding oddly swollen bats.

“I’m sure the pitchers are going, ‘What the heck is that thing?’ ” Russell says.

While the Yankees are drawing headlines for using torpedo bats, players on at least eight MLB teams have tried the bats, from the Chicago Cubs to the Tampa Bay Rays in batting practice, spring training or the regular season. Several of baseball’s 41 approved bat suppliers are making versions of them, from Louisville Slugger and Victus to Chandler and Authentic.

“If all of the manufacturers aren’t already making them, I’m sure they will be soon,” Russell says.

Opinion: Remembering Ai, a remarkably intelligent chimpanzee

We remember Ai, a highly intelligent chimpanzee who lived at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University for most of her life, except the time she escaped and walked around campus.

The near death — and last-minute reprieve — of a trial for an HIV vaccine

A trial was about to launch for a vaccine that would ward off the HIV virus. It would be an incredible breakthrough. Then it looked as if it would be over before it started.

Bessemer data center developer to request rezoning for additional 900 acres

The city’s attorney informed council members of the request on Tuesday, warning that there may be media scrutiny.

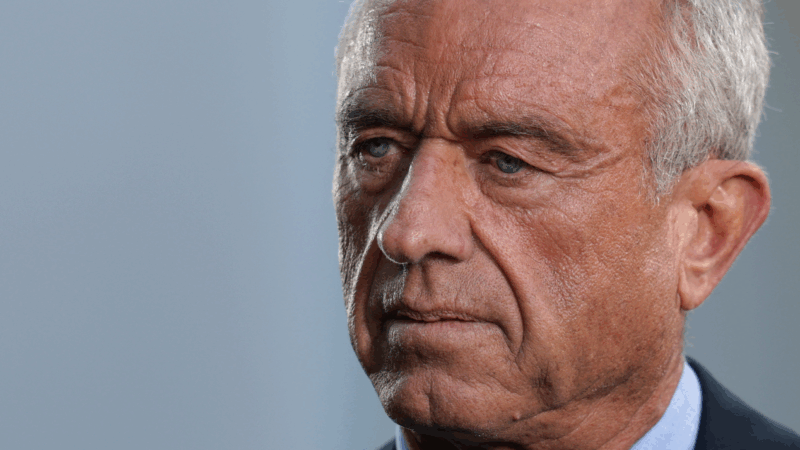

Is RFK Jr.’s Administration for a Healthy America — AHA — in the works or not?

The Administration for a Healthy America is RFK Jr.'s plan to tackle chronic disease, addiction and other persistent problems. But so far it's not being set up like previous new agencies.

Major plumbing headache haunts $13 billion U.S. carrier off the coast of Venezuela

The crew of USS Ford is struggling to handle sewage problems on board the Navy's newest carrier.

Events in Minneapolis show how immigration enforcement has changed. What’s the impact?

Minneapolis is at the center of sweeping, evolving federal immigration push. It demonstrates how different immigration enforcement is under Trump's second administration - and raises questions about the lingering effects on local communities and law enforcement.