How China came to rule the world of rare earth elements

Deep in an underground, World War II-era vault on the outskirts of Frankfurt, Germany, investment manager Louis O’Connor guards his firm’s most valuable assets. The treasure inside? Rare earth elements.

“Make no mistake about it, there’s 3 1/2-meter walls and doors and armed security,” says O’Connor, the CEO of Strategic Metals Invest, a firm that lets individual investors buy into stockpiles of rare earths.

Many so-called rare earth elements are actually quite common, and they are mined globally, but China has a near-monopoly on refining them for use in everyday electronics, like smartphones and speakers, as well as for crucial defense systems, like fighter jets.

When China decided to tighten control over supply chains for seven rare earth elements this spring, O’Connor says he felt the pinch immediately. One investor touring the company’s vault at the time offered on the spot to buy O’Connor’s entire inventory of terbium and dysprosium, two valuable “heavy” rare earth elements, he says.

The episode illustrated the power of China’s dominance over the industry.

“They’re installing what you might call a tap system, where they can turn that tap on and off,” says O’Connor, remarking on China’s recent policy.

That supply chain chokehold has given China a powerful tool it has wielded in a trade war with the United States. Within weeks of China requiring foreign companies to apply for a license to buy rare earths in early April, several U.S. and European corporations said they were forced to shut down production lines. Regaining access to Chinese rare earths was a central point of contention in U.S.-China trade negotiations this spring.

But China did not always enjoy such dominance. Developing an export control regime they could minutely control took decades of sometimes painful trial and error.

Spotting strategic value

For much of the second half of the 20th century, the United States controlled the market on rare earth elements, after prospectors discovered them in Mountain Pass, Calif., in 1949.

China recognized the strategic value of rare earths, and starting in the 1960s, Chinese executives visited Mountain Pass several times, says Mark Smith, who was the CEO at Molycorp, a former rare earths processing company at the Mountain Pass mine.

“We toured them. We explained what we do, allowed them to take pictures and everything else. They took it back to China,” Smith says, who gave tours of Molycorp to Chinese visitors in the 1980s and 1990s.

Chinese refineries then improved on technology, and taking advantage of cheap electricity in China, hundreds of lucrative mining and processing firms in the country popped up to service mostly domestic demand for rare earths.

Loading…

But the industry was highly unregulated and chaotic, as hundreds of small-scale, private mines and refineries competed against one another, undercutting each other’s profits.

“They drive down the price against themselves,” says Chris Ruffle, an investor who has worked in China for decades, including in the metals industry. “They kill themselves.”

“China’s rare earths aren’t being sold at a ‘rare’ price but at an ‘earth’ price,” Xiao Yaqing, a former minister of industry, complained in 2021.

A dirty business

As Chinese producers sought an upper hand in rare earths, they also unleashed unrestrained mining that came at great cost to the environment.

In the early 2000s, Ruffle visited a private rare earths refinery in Jiangsu, a province in southern China. “The thick smoke slightly gave it away,” Ruffle says of the facilities. He describes huge piles of tailings — toxic, metallic by-products from other industrial processes — sitting on the bare ground.

Destructive, small-scale mining was especially prevalent in southern China, where the most valuable, natural deposits of “heavy” rare earth elements are.

“They would mine the side of the hill with their axes and picks and shovels, and then they would dig a hole in the ground, no liners or anything like that at all. Then they poured five gallon buckets of sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid … and let that certain stew for a while,” remembers Smith, who frequently visited China during this period. “When the storms come in, all that acid just washes out.”

The mining left China’s terrain scarred with lasting groundwater and soil pollution. Local residents staged periodic protests against rare earth mining, but the industry provided local governments with abundant revenue, and they repeatedly ignored central government orders to close down dirty mines.

A Chinese media investigation into the industry in 2012 compared the rare earths industry in China during this time to trafficking illegal drugs. “There are generally two types of people who can deal with rare earths: the first is someone who has just been released from prison, and the other is someone who can get someone out of prison. Those who are not afraid of death and leading cadres are all involved,” the state media article said.

Multiple Chinese businesses and individuals declined requests to comment for this story.

Consolidation or bust

By the late 1990s, Beijing had had enough of the domestic price wars and local pollution. It started imposing production and export quotas to incentivize more advanced processing of rare earths. The quotas also aimed to cut down on pollution by setting caps on how much mines and refineries could produce and protected the industry from foreign intervention.

The quotas created two sets of prices, “in effect, two-tier pricing, when exports were limited to the rest of the world that resulted in lower rare earth prices for domestic Chinese consumers,” says Rod Eggert, a professor at the Colorado School of Mines.

There was also a second, unintended consequence to the quotas: they created a thriving smuggling industry. Up to 30% of the country’s rare earth products in the mid-2000s was illegal, smuggled out of China despite state controls, analysts estimate, because of demand from Japan and the U.S.

Then, American and European companies cried foul over the export quotas, and in 2014, the World Trade Organization ruled China could not use them.

But China was unfazed. It was already shifting tactics. It would seek global dominance in rare earths not through controlling the volume of outputs, but instead, by controlling which firms could operate.

A “secret war” to consolidate

Chinese central authorities dubbed the campaign “one plus five”: an ambitious, and often ruthless, effort to winnow down the entire rare earth industry to just six consolidated companies. Authorities called the consolidation their “secret war” against illegal production.

Starting in 2011, provincial authorities were instructed to mount unannounced audits of mines, to seize contraband ore and by-products, and when needed, dynamiting and smashing to pieces illegal mining operations.

“I saw firsthand how the private sector got squeezed out,” says Ruffle, the investor.

Within four years, China declared victory. It announced the closure of dozens of smaller mining and refining companies and guided the mergers of surviving companies into six supersized, mostly state-owned firms, nicknamed the Big Six in China.

Through the Big Six, China could now largely control both supply and price.

“Whereas before you had a lot more competition from different producers, now you get very homogeneous pricing,” says Jan Giese, a Frankfurt-based rare earth trader. “It’s difficult to have competitive bids.”

American upstarts

Unlike metal commodities like nickel or gold, there is no independent exchange for buying and selling rare earth elements.

Because Chinese companies can cause huge price fluctuations depending on how much they decide to produce or export, investors have been wary of pouring money into new ventures in the U.S., say U.S. refining and mining companies.

That has made raising capital to build refining plants a big challenge for American companies trying to break back into the industry.

“They’re putting their money into things like Alphabet and, you know, Amazon and, you know, all the high-flying types of investments and just very, very little, if any, is coming into the mining industry,” says Smith, the former CEO of Molycorp.

Some are still trying. Smith’s new venture, NioCorp, is opening new mines and refining capacity for rare earths in Nebraska.

Phoenix Tailings, a startup in Massachusetts, is also among a handful of U.S. companies prepared to refine rare earths, by refining the tailings, or leftover waste, from mining companies.

“We have to be full speed on the gas to make sure we’re successful here,” says Nicholas Myers, one of the co-founders and CEO.

The company already makes rare earth magnets for automotive and defense companies, and it is currently building a second plant in New Hampshire which the company says can meet about half of the U.S.’ defense needs for rare earth products.

For years, Myers says his company struggled to attract investment at the magnitude needed to compete with Chinese firms in scale.

This year, things changed, after China implemented a licensing system for foreign companies which caused rare earth exports to plummet.

“Definite tone shift,” says Myers, “I think what happened is the end customers, the folks at the big automotive companies or defense primes, realized that they had told their bosses that China would never shut off the supply for them.”

But China did shut off that supply.

The sudden cutoff galvanized U.S. investor interest in rare earths, Myers says. Phoenix Tailings garnered a major round of investment in May, and now, for the first time in decades, the U.S. may refine rare earth elements again.

Emily Feng reported from Burlington, Mass., and Washington, D.C. Aowen Cao contributed research from Beijing.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Now we’re going to take a look at Beijing’s near monopoly on refining rare earths. Emily Feng reports on how China developed a stranglehold on them.

EMILY FENG, BYLINE: Rare earths are now so coveted, some people are stockpiling them in vaults.

LOUIS O’CONNOR: Make no mistake – I mean, there’s 3 1/2-meter walls and doors and armed security.

FENG: That’s Louis O’Connor. He helps run a firm where investors can buy into stocks of rare earths he stores in an underground vault in Germany. China put export restrictions on seven types of rare earths this spring in response to U.S. tariffs, and O’Connor says he and his investors felt the crunch immediately.

O’CONNOR: They’re installing what you might call a tap system where they can turn that tap on and off.

FENG: And when China turned that tap off this spring, the U.S. felt the pinch. But as late as the 1980s, however, it was the U.S. that dominated rare earths at a mine in California called Mountain Pass. Mark Smith used to be an executive at Molycorp, a rare-earth-producing company there.

MARK SMITH: At its heyday, it actually was producing 100% of the europium – which is a heavy rare earth – that the world needed.

FENG: Then China saw the potential of these minerals. They wanted to learn from the U.S. So Smith says starting in the 1960s, Chinese executives began visiting Mountain Pass.

SMITH: We toured them. We explained what we do, allowed them to take pictures and everything else. They took it back to China.

FENG: Then Chinese companies ramped up their production and undercut global prices. But the industry in China at the time was highly unregulated and polluting. Here’s Smith again. He frequently visited China during this period.

SMITH: They would mine the side of the hill. They’d pour five-gallon buckets of sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid, pour their ore in it and let that sit and stew for a while, and then they’d take the liquor back into the five-gallon jugs.

FENG: All of this, of course, created huge environmental problems. And by the late 1990s, Beijing had had enough. It started imposing production and export quotas to stop price wars, limit pollution and limit foreign involvement. Rod Eggert teaches mineral economics at the Colorado School of Mines. He explains these quotas created two sets of prices. These controls also had the unintended consequence of creating a thriving smuggling industry…

ROD EGGERT: And so there was an incentive for undocumented or illegal or unsanctioned exports.

FENG: …To get around export limits. Academics estimate up to a third of the country’s rare earth products in the mid-2000s were illegal – smuggled out of China. Plus, in 2014, the World Trade Organization ruled against those export limits. But China was already shifting tactics.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: (Speaking Mandarin).

FENG: China was consolidating. In 2012, it started policing smaller mines, even blowing up illegal operations.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: (Speaking Mandarin).

FENG: China closed down hundreds of illegal mines and refineries, then formed just six supersized, mostly state-owned firms, nicknamed the Big Six, in China. China could now control both supply and price through the Big Six. And today, Chinese companies basically set the price for rare earths.

(CROSSTALK)

FENG: But American businesses have been trying to find ways to overcome China’s dominance.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: The stuff at the bottom is that chemical that I was talking about that allows you to separate…

FENG: Companies like this one, called Phoenix Tailings – it’s a Massachusetts startup that takes mining waste and extracts the rare earths inside.

I just – I love that you have a vat labeled acid.

(LAUGHTER)

FENG: I will not touch that.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: Please do not.

FENG: They’re one of just a handful of American companies prepared to refine rare earths. Here’s Nick Myers, one of the co-founders.

NICK MYERS: Our primary customers are in the automotive sector.

FENG: But like other American rare earth companies, they say it was hard to get capital and to gain traction, in part because China has so much market share. Then, this year, things changed.

MYERS: Definite tone shift – I think what happened is the folks at the big automotive companies or defense primes realized that they had told their bosses that China would never shut off the supply for them.

FENG: But this year, China did shut off supply. Phoenix Tailings got a big round of investment, and they and other American companies are hoping to finally catch up to China.

Emily Feng, NPR News, Burlington, Massachusetts.

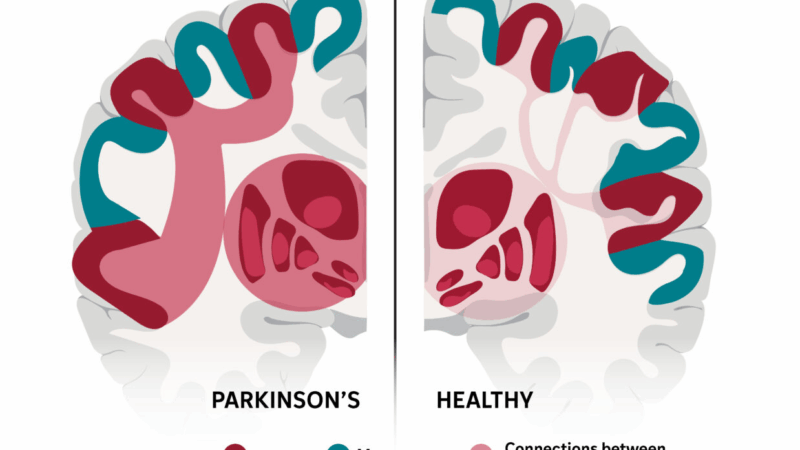

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson's disease appears to disrupt a brain network involved in everything from movement to memory.

How the use of AI and ‘deepfakes’ play a role in the search for Nancy Guthrie

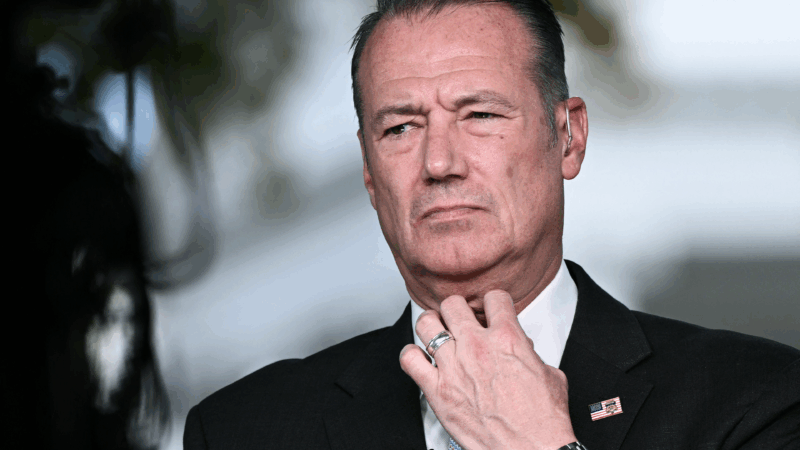

As artificial intelligence becomes more advanced and commonplace, it can be difficult to know what's real and what's not, which has complicated the search for Nancy Guthrie, according to law enforcement. But just how difficult is it?

Hospitals are posting prices for patients. It’s mostly industry using the data

The Trump administration pushed for price transparency in health care. But instead of patients shopping for services, it's mostly health systems and insurers using the information for negotiations.

‘E-bike for your feet’: How bionic sneakers could change human mobility

Nike's battery-powered footwear system, which propels wearers forward, is part of a broader push to help humans move farther and faster.

Immigration officials to testify before House as DHS funding deadline approaches

Congressional Democrats have a list of demands to reform Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But tensions between the two parties are high and the timeline is short – the stopgap bill funding DHS runs out Friday.

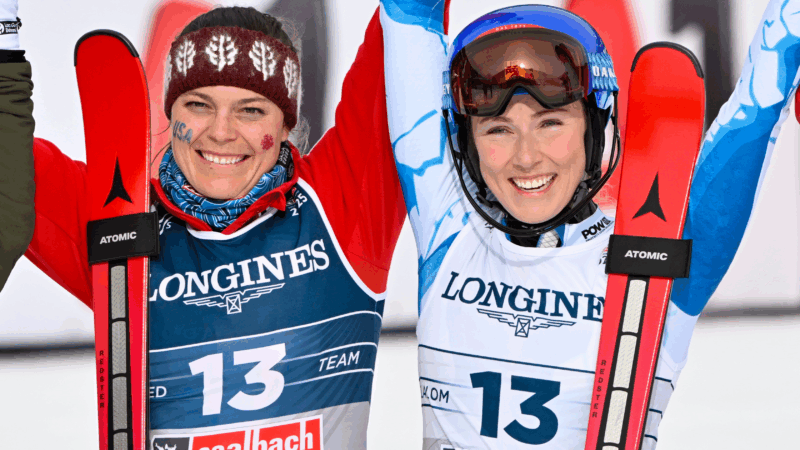

Mikaela Shiffrin set to ski for the first time in the Olympics in team combined event

The team combined event pairs a downhill skier with a slalom skier. The top U.S. duo — the slalom star Shiffrin and Breezy Johnson, who won gold in the downhill on Sunday — is a medal favorite.