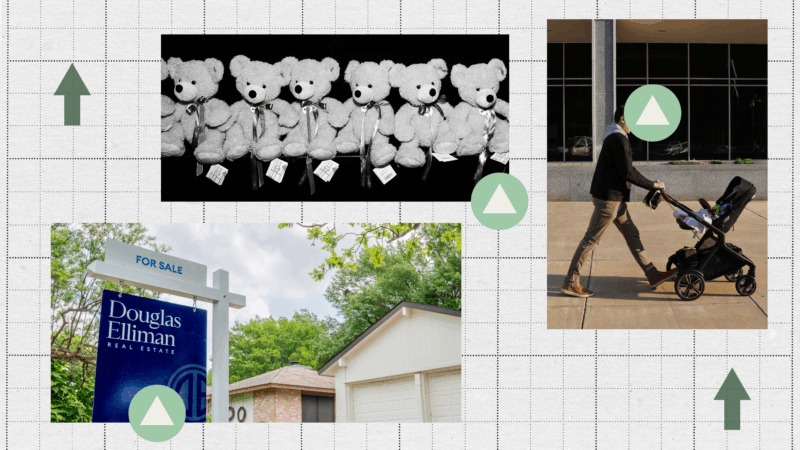

Housing prices are causing some people to have smaller families than planned

NPR’s series Cost of Living: The Price We Pay is examining what’s driving price increases and how people are coping after years of stubborn inflation. How are higher prices changing the way you live? Fill out this form to share your story with NPR.

What’s the item?

Housing

How has the price changed since before the pandemic?

Up 56% since Feb. 2020, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Why has the price gone up?

Low mortgage rates and work-from-home policies spurred a homebuying rush in the first two years of the pandemic, causing home prices to spike. Then mortgage rates shot up in 2022 and homebuying slowed significantly. But prices have stayed high as many current homeowners have locked in low mortgage rates and aren’t in a hurry to sell.

For Ava Rimal, the options became clear: She and her husband could have a second kid, or move to the bigger house in a more upscale area. But they couldn’t afford to do both.

They chose the house.

“I’d rather have one kid that I can give everything to than try to spread it thin between two children just for the sake of having two children,” she says.

Housing costs have risen sharply in recent years, leading people to make some hard choices. To make the math work on housing and daycare and everything else, some Americans are opting to have a smaller family than they had once envisioned.

Rimal says she had always wanted to have two kids. She and her husband married during the pandemic, and had a son not long after. For a time, they all fit well enough into the two-bedroom house in Asbury Park, N.J., the couple had bought in 2016.

But as their son reached preschool, the house started feeling small. They weren’t excited about the local schools. A new plan came into focus when they visited Rimal’s coworker in the South Jersey town of Collingswood, near Philadelphia.

“It looked like a Hallmark movie. There were kids everywhere, and people singing,” she recalls. “It was just nuts.”

So they sold their Asbury Park home, and last June managed to buy a three-bedroom in Collingswood. But it stretched their budget. Their monthly payment is now almost $5,000, more than double what they were paying before. The mortgage rate on their old house was 3% — now it’s 7.25%.

“We bought the house with three bedrooms to kind of preserve the possibility of having another kid. But we didn’t know that the interest rates were going to be so high or that we’d end up spending $100,000 more than we wanted to,” Rimal says.

When they ran the numbers on paying for daycare for a theoretical second child, plus their mortgage payment, it was just too expensive. They decided to be one and done.

Since the pandemic, affording a house has gotten harder for many

The pandemic created a watershed moment in the U.S. housing market.

Many who bought a home before rates shot up in 2022 locked in super low interest rates they can keep forever. That means their housing costs may be significantly lower than those who bought later — but they can also feel locked in place, in a home that no longer fits their needs.

Some who bought a home in the last few years, when both prices and mortgage rates have been high, feel squeezed by monthly payments that leave little cash left over. They stretched to afford a home — and they’re still stretching.

And many who haven’t bought a home yet say they don’t know when they’ll ever be able to afford one. High rents make it hard to save for a down payment. Some people waited for prices or rates to fall so that they could jump in — and they’re still waiting.

The median monthly payment on a home bought in 2024 was $2,207, compared to $1,525 for a home bought in 2021, according to an analysis by Bankrate.

The median sales price for existing single-family homes rose 56% between February 2020 and July of this year, according to data from the National Association of Realtors. And high mortgage rates have further slashed affordability: Rates jumped from pandemic lows below 3% to above 7% earlier this year — though in recent weeks, they’ve dipped below 6.5%.

Loading…

The high cost of housing is even causing some people to conclude they don’t want kids at all.

Chelsea Clouser is 29 and lives in Davis, Calif. She works in fundraising, and her husband teaches high school.

When she was younger, Clouser was interested in having kids. “But then as I’ve gotten older and as I started working and kind of experienced how difficult it is to feel financially comfortable, it’s just become less and less desirable for me,” she says.

Part of that calculation is the cost of housing. Clouser and her husband pay $2,400 a month to rent a one-bedroom apartment that sometimes already feels too small, with just their cat.

Over the last six years, rents nationally rose 17%. Clouser’s rent has gone up every year she’s lived in Davis.

“We want to eventually buy a house. And so if we had a kid, while we’re renting, that would just be so impossible,” she says.

The cost of their rent — plus the fees for parking, storage, and a pet — has made saving up for a down payment difficult. Especially when the cost to buy is so high: Last month the typical home in Davis sold for $843,000.

But even if housing were cheaper, Clouser says she would still have reservations. She worries about the economy and layoffs at work. She doesn’t want the worry of providing enough opportunities for a child, too.

As she and her husband talk through their goals, they weigh the benefits of having a child against how much harder it would make their financial situation. In the end, she says, it “just doesn’t really seem worth it.”

Why supporting a shelter for women is now ‘kind of radioactive’

That's how researcher Beatriz Garcia Nice describes the new U.S. stance under the Trump administration to programs addressing gender-based violence.

Telehealth abortion is in the courts. Share your experience.

Mifepristone is facing another major legal challenge.

Israel launches new strikes in Tehran as public farewell for Khamenei begins

Israel's military said it had begun a "broad wave of strikes" in Tehran Wednesday morning. U.S. officials touted early gains, while Democrats warned the war could widen.

America has a housing affordability crisis. Building houses for rent can help

Developers are building more single-family houses for renting. That can lower prices for both renters and buyers.

As Paralympics approach, U.S. skier Sydney Peterson balances training and research

Sydney Peterson is among the U.S. athletes heading to the 2026 Winter Paralympics. A neuroscientist in training, Peterson is studying movement disorders, similar to her own condition.

ICE has spun a massive surveillance web. We talked to people caught in it

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE and Border Patrol, is using a broad web of surveillance tools — purchased as its budget has ballooned under this administration — to monitor, apprehend and intimidate the people it seeks to deport and the U.S. citizens critical of its policies.