High-speed train from California to Las Vegas tries to slow rising costs

RANCHO CUCAMONGA, Calif. — Brightline West aims to connect Las Vegas and Southern California with high-speed rail.

But the planned terminal is not in Los Angeles, where you might expect, but 40 miles east of downtown Los Angeles.

“We’ve got the best name. Who doesn’t want to say Rancho Cucamonga?,” asks Elisa Cox, assistant city manager for this town of about 170,000 near the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains in Southern California’s Inland Empire.

This is where Brightline West plans to build a terminal to handle millions of travelers a year.

The company broke ground last year on what would be the first true high-speed rail line in the U.S., with trains that can make the 218-mile trip to Las Vegas in just over two hours. The project also aims to ease the notorious traffic congestion between L.A. and Las Vegas that frequently turns Interstate-15 into a parking lot.

But high-speed rail is expensive. So Brightline West has had to make some big compromises to keep costs down — for example, putting the terminal in Rancho Cucamonga instead of downtown L.A., and running track through the median of an interstate, to save on land acquisition costs.

Still, the project is expected to cost at least $12 billion dollars, and likely more. The company has raised about $6.5 billion so far in private financing and federal grants, but it’s warning investors that construction costs are rising. And skeptics worry whether the company can deliver on its promises.

“I think that there’s a lot of risk around it failing, and I wouldn’t have said that a year ago,” said Marc Joffe, a former analyst in the financial industry who’s now a visiting fellow at the California Policy Center, a conservative-leaning think tank.

Brightline’s existing service in South and Central Florida is falling short of its ridership and revenue projections, Joffe notes. And the company recently pushed off an interest payment in July, prompting some ratings agencies to downgrade its bonds.

Investors have some doubts about Brightline West as well, Joffe says, and he believes they’re right to be concerned.

“I think it’ll be late. I think it will generate less revenue than they expect. Between those two things, I don’t think it’ll be successful, at least from a financial point of view,” Joffe said in an interview.

The U.S. is one of the few wealthy countries in the world without a high-speed rail line that travels more than 180 miles per hour. Brightline West is betting it can change that. With top speeds of almost 200 miles per hour, these trains will be faster than Amtrak’s Acela service on the Northeast Corridor, or Brightline’s current service in Florida.

Even the Trump administration — which has tried to strip federal funding from another high-speed rail project in California — is on board with Brightline West so far.

“I would love to see high-speed rail in America,” said U.S. Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy last month. “I don’t think it should just be China, Europe, Japan, others that have high-speed rail.”

Brightline West declined an interview request for this story.

But Asha Jones, the vice president of corporate affairs, laid out some of the company’s plans in a virtual presentation for the board of the San Bernardino, Calif. County Transportation Authority in June. The link between Brightline West and the L.A. regional rail system will be seamless, she said.

“You’ll be able to buy one ticket that will take you from Las Vegas or any of the other pick-ups if you’re going to L.A. or wherever you’re going that Metrolink goes,” she said. “We want it to be quick and efficient.”

Building a terminal in Rancho Cucamonga instead of L.A. should save time and money. It’s not the only move the company has made to keep costs down. For much of the route, the company plans to put the track in the median of an interstate highway, so that it doesn’t have to acquire as much land.

But those compromises come with downsides. The decision to build a single track in the middle of the freeway will limit speeds, for example, and cap the number of trains.

Still, high-speed rail supporters see Brightline West as the best chance to get a train up and running in the U.S. At the groundbreaking in Las Vegas last year, then-transportation secretary Pete Buttigieg helped drive in one of the ceremonial spikes.

“I am firmly convinced that once the first customer buys that first ticket to ride true high-speed rail on American soil, there will be no going back,” Buttigieg said.

For Rancho Cucamonga, the imminent arrival of Brightline West is both a challenge and an opportunity.

“There is nowhere else in the United States that has high-speed rail,” said Elisa Cox, the assistant city manager, in an interview at the future site of Brightline West’s California terminal.

“There is nothing like it yet. So there isn’t necessarily another city to call up and say, like, ‘hey, how did you deal with X, Y, Z?,'” she said. “There is no other example.”

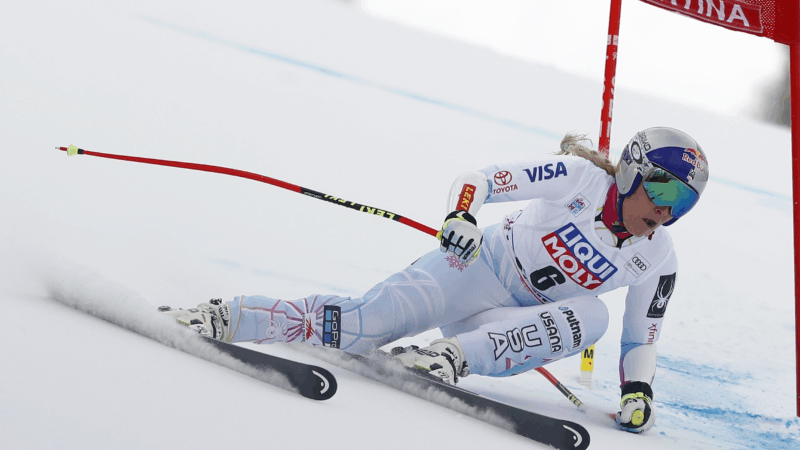

For many U.S. Olympic athletes, Italy feels like home turf

Many spent their careers training on the mountains they'll be competing on at the Winter Games. Lindsey Vonn wanted to stage a comeback on these slopes and Jessie Diggins won her first World Cup there.

Immigrant whose skull was broken in 8 places during ICE arrest says beating was unprovoked

Alberto Castañeda Mondragón was hospitalized with eight skull fractures and five life-threatening brain hemorrhages. Officers claimed he ran into a wall, but medical staff doubted that account.

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.

In this Icelandic drama, a couple quietly drifts apart

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason weaves scenes of quiet domestic life against the backdrop of an arresting landscape in his newest film.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.