Help is growing for the heavy emotional toll cancer takes on young men

It’s been more than seven years, so Benjamin Stein-Lobovits is now able to crack dad jokes about the inoperable brain cancer diagnosis he received, just before his 32nd birthday.

“I like to say that I turned 30-tumor,” he says.

Ba-dum-tssh.

But, at the time, the news was devastating; Stein-Lobovits spent many months sobbing on the couch, immobilized by loss and fear.

“You feel so beat up and powerless,” says Stein-Lobovits, who quit his job as a Silicon Valley programmer, having lost his balance and ability to type quickly. “It’s such a shock to your ego, your sense of being as a man,” he explains.

He didn’t want to be seen in this emotionally vulnerable state by other people, though he was actually starved for camaraderie and comfort.

Coping with cancer is rarely easy for anyone, but men tend to fare worse — emotionally and physically — than women. Evidence shows male survivors isolate more, seek less peer and other support and, alarmingly, die earlier.

People with cancer are living longer today because of better detection and treatments. There are more than 18.6 million cancer survivors in the U.S., and their ranks are growing. But they’re also living longer with cancer’s after effects. This series Life, After Diagnosis explores their stories.

Facing treatment alone

Gender differences play out every day in Dr. James Hu‘s office. The University of Southern California sarcoma specialist says his female patients very often arrive at appointments accompanied by family or friends for support. “Male patients? They come by themselves, they get their therapy and they’re outta here,” he says.

This can come at the ultimate cost: Research shows men under 40 are at highest risk of suicide among cancer survivors.

“In fact, the highest risk seems to be way out beyond the initial year or two of treatment,” Hu says, meaning that for men, mental health doesn’t improve after cancer, but continues to deteriorate, even years after treatment.

Stein-Lobovits, now 39, understands why.

Treatment and health issues forced him to give up his lucrative programming career, he became a stay-at-home dad to his young girls in Oakland, leaning heavily on his wife, who returned to full-time work. The grape-sized, Stage 4 tumor on his brain stem made his movements and memories shaky.

“Everything is a little bit harder, like texting, emailing,” says Stein-Lobovits, who’s been on an experimental treatment that’s kept his disease from growing. “I have balance issues — walking, cognition, memory. Short-term memory loss is huge for me. So much of cancer is the loss of the self and loss of control. That’s probably the hardest thing.”

The defeat, he says, can feel complete.

Take parenting, for example. It fills him with joy and purpose, he says. But it also spotlights his limitations. He forgets his kids’ dentist appointments and groceries to buy. He then feels guilty for the extra burden that places on his wife.

“Because for her it’s so hard to separate what’s just regular forgetfulness, what’s chemo brain, what’s just being a tired parent,” Stein-Lobovits says. There’s no legitimate place for the frustration to go, he says, it just compounds the strain cancer causes.

A support group called Man Up to Cancer

Trevor Maxwell says his cancer diagnosis in 2018 at age 41 reordered many of his relationships, too.

Maxwell, a journalist, comes from generations of rugged Maine stock who split their own firewood. Stage 4 colon cancer and its many surgeries and treatments sapped that strength and independence from him. “I struggled with crippling anxiety and depression,” and he spent a blur of months listless or crying in bed, he says. “I struggled with deep shame,” he says, because of his inability to fill his prior role as father, worker, and husband. It vacated his self-worth.

After many months, Maxwell’s wife and daughters persuaded him to join cancer support groups, where he met mostly women, and notably few men. He thought a lot about why that might be. “In my mind, it comes down to cultural norms and conditioning,” he says. “There are thousands of guys out there just like me who felt devastated. But they are just too proud, angry, ashamed or depressed to seek it out.”

So nearly six years ago, Maxwell decided to start Man Up to Cancer, a group that sponsors meetings, outreach and retreats for fellow male survivors. Maxwell, who is doing well on his treatments now, says the group’s goal is to provide fellowship and emotional outreach to men who need it. It ends up being a profound experience for many of the members who join.

“We’ve got a lot of people who do traditionally masculine jobs like truck drivers, and then they’re also coming to our Zoom meetings, and they’re not afraid to cry there,” he says. “And they’re not afraid to say, ‘I love you’ to the other guys in our group. That’s the culture change that we’re seeking.”

Across the country in Oakland, Benjamin Stein-Lobovits does his own outreach, too, telling men he meets in support groups, “‘It’s OK to be scared, but it’s OK to be vocal about being scared. And it’s OK to get help for being scared'” — words he once needed to hear.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

Dealing with cancer and its aftermath is never easy, and men tend to fare worse, emotionally and physically. NPR’s Yuki Noguchi explores why as part of her series Life After Diagnosis.

YUKI NOGUCHI, BYLINE: It’s been over seven years, so Benjamin Stein-Lobovits is now able to crack dad jokes about the inoperable brain cancer diagnosis he got on the eve of his 32nd birthday.

BENJAMIN STEIN-LOBOVITS: I like to say that I turned 30-tumor.

NOGUCHI: But at the time, he was devastated. Stein-Lobovits spent a year sobbing and immobilized by loss and fear.

STEIN-LOBOVITS: You feel so beat up and powerless. It’s such a shock to your ego, your sense of being. You know, as a man, I could totally see not wanting to show that side.

NOGUCHI: The emasculation, he says, felt complete. He’d given up his Silicon Valley programming job and relied heavily on his wife. He became a stay-at-home dad to his young girls in Oakland. But the grape-size Stage 4 tumor and ongoing treatment for it makes him shaky.

STEIN-LOBOVITS: Everything is a little bit harder, like texting, emailing. I have balance issues, walking. Short-term memory loss is huge for me. So much of cancer and everything is the loss of the self and loss of control. That’s probably the hardest thing.

NOGUCHI: Evidence shows men tend not to cope well with cancer. They isolate more, seek less support and, alarmingly, die earlier. James Hu, an oncologist with the University of Southern California, sees it all the time. Female patients usually come to appointments with support people.

JAMES HU: Male patients – they come by themselves, they get their therapy, and they’re out of here.

NOGUCHI: Hu says research shows men under 40 are at highest risk of suicide among cancer survivors.

HU: In fact, the highest risk seems to be way out beyond the initial year or two of treatment.

NOGUCHI: In other words, their mental health continues deteriorating years after treatment. Benjamin Stein-Lobovits understands why. Parenting, for example, fills him with joy and purpose, but it also spotlights his limitations when he forgets kids’ dentist appointments or groceries to buy. He then feels guilty for the extra burden that places on his wife.

STEIN-LOBOVITS: Because for her, it’s so hard to separate what’s just regular forgetfulness, what’s chemo brain, what’s just being a tired parent. Where can she push on me?

NOGUCHI: Trevor Maxwell says cancer reordered his rules in the world, too. He comes from generations who split their own firewood in Maine. Stage 4 colon cancer stole that strength and independence.

TREVOR MAXWELL: I struggled with crippling anxiety and depression. I struggled with deep shame.

NOGUCHI: His wife and daughters eventually persuaded him to join support groups, where he met mostly women and almost no men.

MAXWELL: In my mind, it comes down to cultural norms and conditioning. There are thousands of guys out there just like me who felt devastated, but they are just too proud, angry, ashamed or depressed to seek it out.

NOGUCHI: So five years ago, Maxwell, who remains in treatment, started Man Up to Cancer. The group posts outreach, online groups and retreats for male survivors.

MAXWELL: And we’ve got a lot of people who do traditionally masculine jobs, like truck drivers, and then they’re also coming to our Zoom meetings. And they’re not afraid to cry there, and they’re not afraid to say, I love you to the other guys in our group. That’s the culture change that we’re seeking.

NOGUCHI: Across the country in Oakland, Benjamin Stein-Lobovits carries a similar message to male patients he meets.

STEIN-LOBOVITS: It’s OK to be scared. It’s OK to be vocal about being scared, and it’s OK to get help for being scared.

NOGUCHI: Words he once needed to hear.

Yuki Noguchi, NPR News.

SHAPIRO: And for many other stories of cancer survivorship in our series Life After Diagnosis, visit npr.org.

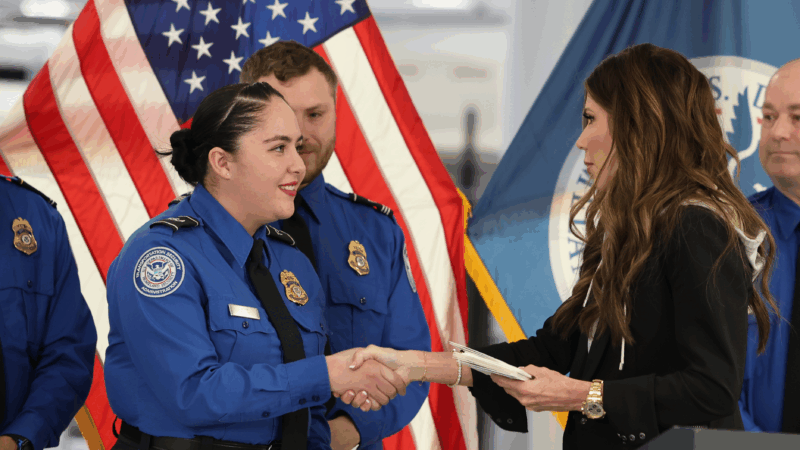

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

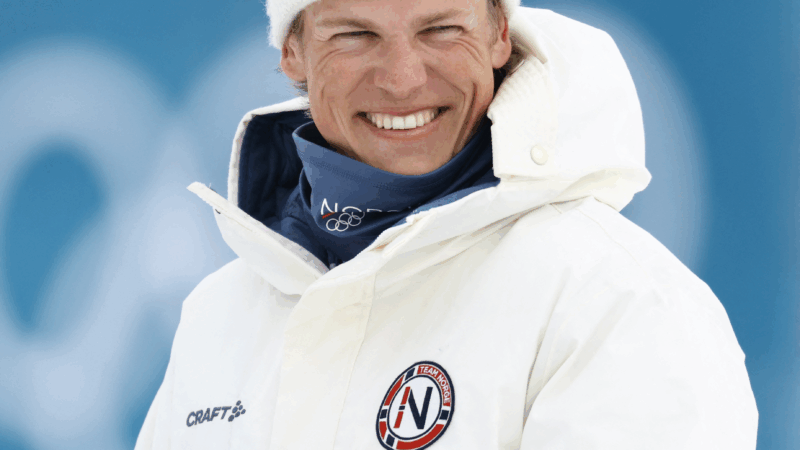

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.