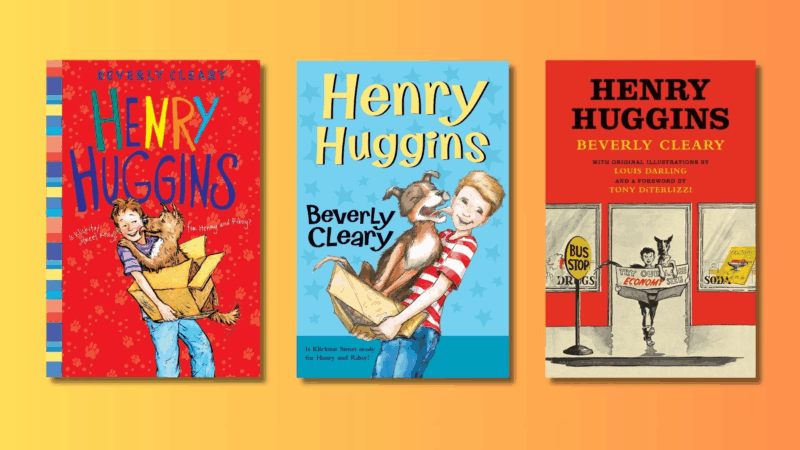

Happy 75th birthday to Henry Huggins, Ramona Quimby’s big-kid neighbor

When Beverly Cleary’s fictional Henry Huggins made his debut in 1950, he was a third grader whose “hair looked like a scrubbing brush and most of his grown-up front teeth were in.”

He was also bored. Apart from having his tonsils out and falling out of a cherry tree, “nothing much happened to Henry.”

But pretty soon after we meet him, by page three in fact, Henry comes upon a scrawny mutt who stares at him eating an ice cream cone – and the adventures begin. “When Henry licked, he licked. When Henry swallowed, he swallowed,” Cleary wrote of the dog. Henry adopts the hungry stray, calls him Ribsy and the two become fast, fun-loving friends prone to mishaps.

“I thought he was the coolest little kid,” said writer Joe Bonomo who started reading Henry Huggins books growing up in Wheaton, Md., in the 1970s. “And not in the conventional way of that word.”

Unlike the cowboys and astronauts in many of the books kids read in those days, Bonomo said Henry was relatable. For example, he looked for ways to spend his allowance.

“He was kind of a loner, but not in a bad way or a sad way,” said Bonomo, an English professor at Northern Illinois University. “He would go to this little dime store and this little fish store. And that’s exactly what I did in my allowance walks. He would entertain himself for hours on end, just by walking and imagining things and running into fun little adventures with his dog.”

Michael Dirda, a Pulitzer Prize-winning literary journalist and columnist for The Washington Post said Beverly Cleary “taught me to read.” And it started with Henry Huggins.

“I remember opening it and being enchanted from the get go,” he said.

Like Bonomo, Dirda related to Henry. “I had a skinny dog as well at the time whose name was Rinny (the nickname for the canine in the movie Rin Tin Tin), which is a little bit like Ribsy. And so that was probably an extra factor in my being drawn to this book,” he said.

Henry Huggins’ moral dilemma

For Dirda, the ending of the book was a revelation.

In the last chapter of the first Henry Huggins (spoiler alert if you haven’t read it!), an older boy comes looking for Henry after seeing a picture of him and Ribsy in the local paper. When he sees the dog, he shouts “Dizzy!” The dog jumps up on the boy, licks his hands and wags his tail.

Cleary writes: “A terrible thought came to Henry. Ribsy must have belonged to the boy before he found him in the drugstore over a year ago.”

Both boys claim ownership of the dog and tell of how much they care for him. The kids decide to have a contest to let Ribsy choose who gets to keep him.

Each boy stands “twenty squares down the sidewalk in opposite directions” of the dog. On “Go,” the older boy yells “Here Dizzy!” while Henry yells “Here Ribsy!” The tension builds as Ribsy seems torn, wagging his tail when he looks back and forth at both boys. Ultimately, he walks toward Henry.

“I was glad Henry got to keep his dog,” Dirda remembers. “But then I thought, ‘The other guy, he loved the dog, too. And is it right that Henry should take his dog?'”

Dirda has written about how Henry Huggins was the first book that forced him to confront a moral dilemma.

“All these things ran through my head as a kid. And it was at that point that I started to recognize that books were not simple stories with all these Disney kind of happy endings where everything works out perfectly for everybody and everyone is happy,” said Dirda. It showed him that “in fact, life is much more complicated and that there are some issues where there isn’t a clear cut answer.”

A different dilemma: Native American stereotypes

For decades, Cleary has been praised for her authenticity when describing the experiences of average, middle-class kids. In 1999, Beverly Cleary told NPR, “I think children like to find themselves in books.” But her lead characters are white, and some of the plotlines perpetuate stereotypes.

In more than one Henry book, he pretends to be an American Indian. He’s cast as “Second Indian” in a school play: He wears a robe and a feather from his mother’s duster and says “Ugh!” In another book, his mother pretends to be afraid of him when he’s dressed up as an Indian for Halloween.

Debbie Reese, who writes the blog American Indians In Children’s Literature, says that while she understands why Henry Huggins is popular, she worries that white kids might “read right through that problematic content … and not recognize it as harmful or a misrepresentation.”

But Reese says the offensive text shouldn’t be excised. She advises educators and parents to make it a teachable moment and tell kids: “Oh, here’s a mistake. That’s not true. Native people didn’t do this or they didn’t look like that. I would like them to take it head on and say that it’s a mistake.”

Reese wants young readers and their families to know that “books are not sacred. They are just someone’s words, someone’s stories. And some of those stories are wrong.” At the same time, Reese said she “wasn’t surprised that it had problematic content because most of those classic books do.”

To date, Cleary’s first novel has sold more than 3 million copies worldwide. She wrote five more Henry Huggins books, with the final one in the series revolving around his canine companion Ribsy. Another character in the series, his mischievous neighbor Ramona Quimby, was so popular that Cleary gave her an eponymous series of her own.

Meghan Sullivan edited this story for broadcast and digital.

Ukraine’s combat amputees cling to hope as a weapon of war

Along with a growing number of war-wounded amputees, Mykhailo Varvarych and Iryna Botvynska are navigating an altered destiny after Varvarych lost both his legs during the Russian invasion.

University students hold new protests in Iran around memorials for those killed

Iran's state news agency said students protested at five universities in the capital, Tehran, and one in the city of Mashhad on Sunday.

Pakistan claims to have killed at least 70 militants in strikes along Afghan border

Pakistan's military killed at least 70 militants in strikes along the border with Afghanistan early Sunday, the deputy interior minister said.

Team USA faces tough Canadian squad in Olympic gold medal hockey game

In the first Olympics with stars of the NHL competing in over a decade, a talent-packed Team USA faces a tough test against Canada.

PHOTOS: Your car has a lot to say about who you are

Photographer Martin Roemer visited 22 countries — from the U.S. to Senegal to India — to show how our identities are connected to our mode of transportation.

Looking for life purpose? Start with building social ties

Research shows that having a sense of purpose can lower stress levels and boost our mental health. Finding meaning may not have to be an ambitious project.