French Champagne-makers wonder: Is it time to move on from the U.S. market?

VERTUS, France — Walking through his family’s vineyard, fifth-generation Champagne-maker Charles Fourny runs his hand over Chardonnay vines planted by his grandfather more than 70 years ago. For decades, Fourny says his business has relied on a vital market: the United States.

In 2024, American consumers imported 26.9 million bottles of Champagne, making the U.S. the world’s largest Champagne export market.

Shipments to the U.S. accounted for 18% of Fourny’s exports last year. But now, he’s questioning whether he can continue to depend on the U.S.

Even with President Trump’s 90-day pause on tariffs, uncertainty about future trade policies has shaken the long-standing relationship between French Champagne producers and American buyers.

For Fourny, it’s not just about the bottom line. It’s about a trust that feels increasingly fragile.

“We do not trust the [U.S.], because we don’t know what will happen,” Fourny says. “More and more, you have the impression that you are enemies.”

In recent months, the Trump administration’s threats around European wine tariffs have shifted repeatedly, making it nearly impossible for producers and importers to plan ahead.

“We spoke about 200%, then 20% … perhaps tomorrow it will be 6,000%!” Fourny jokes, shaking his head.

In March, President Trump floated the idea of slapping tariffs as high as 200% on European wine imports. A few weeks later, on April 2, he scaled that proposal back to a 20% tariff. Then on April 9, the White House announced a 90-day reprieve, temporarily lowering tariffs on EU wine to 10%.

But that pause is only temporary. After the 90-day period, tariffs could rise again, possibly back to 20%, or even higher.

For Fourny, this unpredictable environment means it’s time to look beyond the U.S. market, seeking stability in places like Brazil.

“We cannot wait for a decision,” Fourny says of the impending tariffs. “We have a company to run, and we need to act in order to keep our business moving.”

A fragile ecosystem

The United States has long been the largest importer of Champagne, helping drive the industry’s growth.

But on the other side of the Atlantic, American wine importers say they’re feeling the squeeze, too.

“It’s just a horrific kind of self-inflicted wound on American companies,” says Harmon Skurnik, a New York-based importer and board member of the U.S. Wine Trade Alliance.

In a worst-case scenario, he says, wines from abroad could become more expensive and harder to find on U.S. shelves. And homegrown American wines can’t simply fill in the gap.

“We can’t buy as much American wine, not to mention the fact that these products are just not as fungible,” Skurnik says. “The French have a term called terroir, meaning the wine reflects the place it comes from. A French Chardonnay doesn’t taste anything like an American Chardonnay. These products are unique.”

American winemakers, especially those in California, are worried as well. They fear that strained distributors, weighed down by the uncertainty around tariffs, could have less ability to buy and sell domestic wine, threatening their short-term stability.

Not everyone is mourning the shift.

In the heart of Épernay, the Champagne region’s capital, a group of American tourists who came to sip bubbly were quick to voice support for the tariffs.

“We’re tariffing a luxury item,” says Justin Fishman, a 29-year-old from Kansas City, Kan.

“Champagne is not something everybody needs on a daily basis.”

Fishman’s friend Joseph Psyck, who is from Kentucky, agrees.

Though his own drink of choice isn’t exactly affected by tariffs.

“I’m gonna drink what I want at home, no matter what,” he says, laughing. “Bourbon.”

Back at Fourny’s estate in Vertus, he offers a bittersweet toast.

Fourny says he wishes Trump realized that all this is more than just about champagne.

“When you do that with a country, it’s not business … it’s a long-term relationship with people,” he says.

And once that’s uncorked, it may not be so easy to bottle it back up again.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

For decades, producers for Champagne in France have relied on U.S. buyers, but U.S. tariffs and tariff threats have some vintage producers saying that era is over. Many European winemakers no longer see the United States as a market they can count on, as NPR’s Rebecca Rosman discovered in France’s Champagne region.

CHARLES FOURNY: So here you can see Chardonnay vines.

REBECCA ROSMAN, BYLINE: Fifth-generation champagne maker Charles Fourny is showing me his family tree in the form of a kind of family vine. These vines were planted by his grandfather over 70 years ago and still bear fruit today.

FOURNY: And we hope that our kids will go on pruning the same wine.

ROSMAN: Same wine, same vines, but maybe not the same sales strategy. Fourny has spent nearly 30 years cultivating ties with American distributors, but now he’s facing a new reality – uncertainty about the future of his exports to the U.S.

FOURNY: We do not trust because now we say we don’t know what will happen. You have really the impression that you are enemies.

ROSMAN: And President Trump’s 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs hasn’t helped, he says. He finds Trump’s decision-making too volatile and still doesn’t know at what percent Champagne will be taxed under the new tariffs.

FOURNY: We spoke about 200, now it’s 20, and perhaps tomorrow it will be 6,000.

ROSMAN: Which is why he’s now looking to pivot.

(SOUNDBITE OF FOOTSTEPS)

ROSMAN: Fourny leads me down into a chilly wine cellar where thousands of bottles are stacked and ready for export. Today, 18% of his sales go to the U.S., but he says he’s shifting focus to more stable markets like Brazil. It’s a tough new reality. For years, the U.S. was France’s top Champagne buyer, a driver of both growth and prestige. But this uncertainty goes both ways.

HARMON SKURNIK: It’s just a horrific kind of self-inflicted wound on American companies.

ROSMAN: Harmon Skurnik is a New York-based wine importer. In a worst-case scenario, he says, wines from abroad could disappear from American shelves entirely, and American wines can’t simply fill in the gap.

SKURNIK: We can’t buy as much American wine. Not to mention the fact that these products are just – are not fungible.

ROSMAN: In other words, California bubbly isn’t a perfect substitute, and the fallout could affect domestic sales, too. Skurnik says this will eventually trickle down to American consumers, who will likely have to pay a higher price on imported wines or change the way they drink.

Back in the Champagne region, just steps off the famous Boulevard de Champagne, I stumble upon a group of American bubbly drinkers who tell me they actually support Trump’s tariffs. One of them is 29-year-old Justin Fishman.

JUSTIN FISHMAN: We’re tariffing a luxury item, I would say. Like, Champagne’s not something that everybody needs on a daily basis.

ROSMAN: Fishman’s friend Joseph Psyck from Kentucky agrees, though his drink of choice isn’t exactly under threat.

JOSEPH PSYCK: I’m going to drink what I want to drink at home, no matter what.

ROSMAN: What do you want to drink at home?

PSYCK: Bourbon.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHAMPAGNE POURING)

ROSMAN: Back at Fourny’s estate, he offers a bittersweet toast.

FOURNY: Cheers, and…

ROSMAN: OK, cheers. Santé.

Fourny says he wishes Trump realized that all this is more than just about Champagne.

FOURNY: You know, when you do that with a country, it’s not a business – it’s a long-term relationship with the people.

ROSMAN: And once that’s uncorked, it may not be so easy to bottle it back up again. Rebecca Rosman, NPR News, the Champagne region, France.

(SOUNDBITE OF ALEXIS FFRENCH’S “BLUEBIRD”)

U.S. unexpectedly adds 130,000 jobs in January after a weak 2025

U.S. employers added 130,000 jobs in January as the unemployment rate dipped to 4.3% from 4.4% in December. Annual revisions show that job growth last year was far weaker than initially reported.

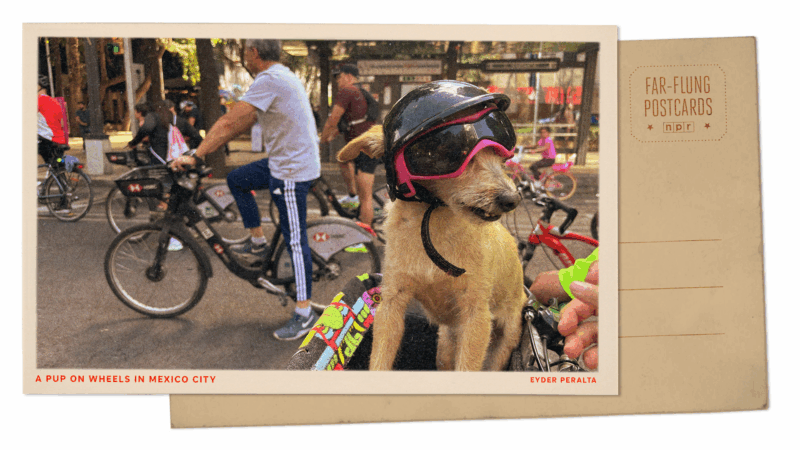

Greetings from Mexico City’s iconic boulevard, where a dog on a bike steals the show

Every week, more than 100,000 people ride bikes, skates and rollerblades past some of the best-known parts of Mexico's capital. And sometimes their dogs join them too.

February may be short on days — but it boasts a long list of new books

The shortest month of the year is packed with highly anticipated new releases, including books from Michael Pollan, Tayari Jones and the late Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa.

Shootings at school and home in British Columbia, Canada, leave 10 dead

A shooting at a school in British Columbia left seven people dead, while two more were found dead at a nearby home, authorities said. A woman who police believe to be the shooter also was killed.

Trump’s EPA plans to end a key climate pollution regulation

The Environmental Protection Agency is eliminating a Clean Air Act finding from 2009 that is the basis for much of the federal government's actions to rein in climate change.

The U.S. claims China is conducting secret nuclear tests. Here’s what that means

The allegations were leveled by U.S. officials late last week. Arms control experts worry that norms against nuclear testing are unraveling.