Former commissioner of flooded Texas county says siren system would have saved lives

A former commissioner of a flood-ravaged Texas county says a siren warning system would have saved lives and that he believes state officials will act promptly to implement a warning system.

Tom Moser, who served as Kerr County commissioner from 2012 to 2021, told Morning Edition he advocated for a flood warning system with sirens in 2016 after a deadly flood in nearby Wimberley. That system was never built because commissioners were denied funding from state grants and there was public pushback.

Locals were concerned about the more than $1 million price tag. “People did not like the idea of sirens throughout the county,” he added.

The central Texas floods killed at least 109 people over the Fourth of July holiday weekend and left more than 160 missing. Many of them are children, most of whom were attending summer camp. Questions have loomed since the floods about what emergency plans were in place.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott says investigations into storm preparation and response are likely to begin later this week, as state lawmakers prepare for a special session to address the disaster.

Moser says state and local officials are likely to act on implementing more effective warning systems now after the most recent disaster.

“I think it will be more robust, more reliable, more effective. And I don’t think it’s going to take very long to do,” Moser said. “Probably a couple of years at most. At most, a few million dollars, not billions, but a few million dollars to do it. And it can be done.”

NPR’s Michel Martin spoke with Moser about what the county and state can do to prevent loss of life during future severe weather events.

The following excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

Michel Martin: Do you think that the county could have done more to warn and protect people?

Tom Moser: Well, let me answer it this way. The county has an emergency management plan which delineates exactly what to do in case of a flood. And it tells who’s responsible for what and who’s supporting what. So I’m sure that — I don’t know this factually — I’m sure they followed that emergency management plan. So I wouldn’t have any comment beyond that.

Martin: Earlier this year, the state legislature failed to get a bill out of committee that would have created a statewide funding mechanism for sirens and emergency alerts. And I’m wondering if you think that this tragedy, as terrible as it was, is going to spur them to reconsider that?

Moser: Well, in a positive sense, on this tragic thing, I think it will happen. I think it will be more robust, more reliable, more effective. And I don’t think it’s going to take very long to do. Probably a couple of years at most. At most, a few million dollars, not billions, but a few million dollars to do it. And it can be done. We’re going to do it and use all the current technology that exists and blend those technologies together to give a very, very effective early warning system.

Martin: I want to mention, though, you have extensive experience in product management. You were a project manager for NASA for some like two decades now. Do you think there are other measures that could prevent a similar tragedy in the future, since you had a lot of time to think about it?

Moser: I think there’s technology that exists today. There’s topographical maps that are digitized that can be used to identify and characterize the terrain. There’s ways to predict currently and and with more precision what we think rainfall is going to fall. And then with models, you can determine where the rainfall is going to be and where it’s going to go and what the levels are going to be downstream. I think that’s the thing that exists today that didn’t exist in the past. And believe it or not, use artificial intelligence to bring all that data together and help guide the direction of which alarms should be sent.

Martin: I do have to ask, though, if you feel that had this warning system been built, that lives might have been saved.

Moser: Yes, if the sirens were there, from what I know, just listening to the media and hearing it. I’m not there. I haven’t been involved in, you know, the rescue or the day to day things that are going on right now. But yeah, I think if sirens were there, clearly people would have known about it. Would it have saved everybody? No, I don’t think so. I think this was an event that’s probably one chance in a million of happening.

Martin: So I just wanted to ask what thoughts you have now about what else needs to happen going forward. And it’s also a difficult question to ask because people love this area and they love their homes. And there’s so many memories that people have attached to these areas. But do you think that people should consider relocating?

Moser: Well, I don’t think they should consider relocating. I think they should consider where they’re building in proximity to rising water. Develop the system that I just delineated a while ago and — those are tools that can identify flooding in a particular area — make that same tool available all over. But use the same analytical capability to build a system and use it to integrate and use the same information that exists wherever it is throughout the United States. And I think that would benefit everybody. And it’s not a huge expense and it can be done very quickly, I’m convinced.

This web story was edited by Olivia Hampton and Obed Manuel contributed. The radio story was edited by HJ Mai.

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

As you just heard, people are starting to raise questions about why so many people did not get effective warnings ahead of the flood disaster last weekend in Kerr County, Texas. Back in 2016, county commissioners debated whether to install a flood warning system that would have set off loud sirens. That system was never built. Former Kerr County Commissioner Tom Moser pushed for the warning system, and he’s with us on the line now to tell us more about it. Good morning. Thank you for joining us.

TOM MOSER: Good morning. Good morning.

MARTIN: So tell me why you and some others called for a warning – a flood warning system nearly a decade ago.

MOSER: Well, it was in 2015, I believe. There was a major flood south of Kerrville in Wimberley, Texas, I believe along the Blanco River. Excuse me if that’s not exact correct on the river. But after that flood, which killed a family and perhaps some others, they installed or created and developed a flood warning system which included sirens. But to advance that and to notify the system to activate, they put in markers along the river and sensors of what the river level was. So I looked at that at that time and brought it back to Kerrville, had an engineer do an expansion on defining the project which could be built in Kerrville, which included sensors along the river and other types of devices to say there’s an imminent flood, and to have sirens as part of it.

We had a meeting with all county officials, city officials and other people in the community – 40 or 50 people. I chaired that meeting. And one of the things it said – here’s the plan. Here’s what we want to do. It’s going to cost, you know, X number of dollars, a million-plus dollars. And we – but one of the things that came out was people did not like the idea of sirens throughout the county. So we listened to that. And we took sirens out of the project just because there was a big resistance to sirens throughout, just primarily because sirens and other warning systems go off when they don’t need to.

MARTIN: Oh, sometimes…

MOSER: So we took that out.

MARTIN: …You have false alarms. Right. OK. But what else?

MOSER: Right. So we pursued our funding with the state grants. We did not get the funding for the state grants. But the most probable cause of people dying, and based on history, was people going across low water crossings on the Guadalupe River when floods occurred. So what we did is we put up gauges on all of those crossings so people could know when it was safe to cross. And that was part of the project at that time.

MARTIN: Did you…

MOSER: So that was it in a nutshell.

MARTIN: So do you think it was primarily the cost that was the barrier?

MOSER: No.

MARTIN: Or people didn’t think it was important. Or they didn’t think it was necessary.

MOSER: Well, it was – we did – cost was the barrier in implementing the whole program without the sirens, yes. Cost was the barrier. And we applied for several years to get a grant for that. We were not successful in doing it.

MARTIN: So here’s a hard question. And as a former official, I don’t know how you feel about this, but do you think that the county could have done more to warn and protect people?

MOSER: Well, let me answer it this way. The county has a emergency management plan which delineates exactly what to do in case of a flood, OK? And it tells who’s responsible for what and who’s supporting what. So I’m sure that – I don’t know this factually – I’m sure they followed that emergency management plan, so I wouldn’t have any comment beyond that.

MARTIN: OK. So earlier this year, the state legislature failed to get a bill out of committee that would have created a statewide funding mechanism for sirens and emergency alerts. And I’m wondering if you think that this tragedy, as terrible as it was, is going to spur them to reconsider that.

MOSER: Well, in a positive sense on this tragic thing, I think it will happen, OK? I think it will be more robust, more reliable, more effective. And I don’t think it’s going to take very long to do – probably a couple years at most, at most a few million dollar – bot billions, but a few million dollars to do it. And it can be done. I mean, it’s just going to take – we’re going to do it and use all the current technology that exists and blend those technologies together to give a very, very effective early warning system.

MARTIN: I want to mention, though, you have extensive experience. I mean, like, I know you’re a modest man and you don’t want to talk about this, but you have extensive experience in product management. You were a project manager for NASA for some, like, two decades now, so you have managed, you know, complex systems. Do you think there are other measures that could prevent a similar tragedy in the future, since you had a lot of time to think about it?

MOSER: Well, yeah. I think there’s technology that exists today. There’s topographical maps that are digitized that can be used to identify and characterize the terrain. There’s ways to predict it currently and with more precision, where we think rainfall’s going to fall. And then with that, with models, you can determine where the rainfall’s going to be and where it’s going to go and what the levels are going to be downstream. Yes, I think that that’s a thing that exists today that didn’t exist in the past. And, believe it or not, use artificial intelligence to bring all that data together and help guide the direction of which alarm should be sent.

MARTIN: I do have to ask, though, if you feel that had this warning system been built, that lives might have been saved.

MOSER: Yes. Yes. It – if the sirens were there, and from what I know, just listening to the media and hearing it – I’m not there. I wasn’t been – hadn’t been involved in, you know, the rescue or the day-to-day things that are going on right now. But, yeah, I think if sirens were there, clearly, people would have known about it. Would it have saved everybody? No, I don’t think so. I think this was an event that’s probably one chance in a million of happening.

MARTIN: So I just wanted to ask what thoughts you have now about what else needs to happen kind of going forward. And I – and it’s also a difficult question to ask because people love this area, and they love their homes, and there are so many memories that people have attached to these areas. But do you think that people should consider relocating?

MOSER: Well, I don’t think they should consider relocating. I think they should consider where they’re building in proximity to rising water. That’s clearly, OK? But I think develop the system that I just delineated a while ago and make that – those are tools that can identify flooding in a particular area. Make that same tool available all over. I understand there’s flooding in Ruidoso, New Mexico, right now. So – and people perhaps are dying. I’m not sure. But use this same analytical capability – OK? – to build a system and use it to – and integrate and use the same information that exists wherever it is, throughout the United States. Develop a tool that’s applicable everywhere. And I think that would benefit everybody. And it’s not a huge expense item. And it could be done very quickly, I’m convinced.

MARTIN: That’s Tom Moser. He’s a former Kerr County commissioner who advocated for a flood warning system back in 2016. Mr. Moser, thanks so much for talking to us.

MOSER: You’re quite welcome.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

FBI release photos and video of potential suspect in Guthrie disappearance

An armed, masked subject was caught on Nancy Guthrie's front doorbell camera one the morning she disappeared.

Reporter’s notebook: A Dutch speedskater and a U.S. influencer walk into a bar …

NPR's Rachel Treisman took a pause from watching figure skaters break records to see speed skaters break records. Plus, the surreal experience of watching backflip artist Ilia Malinin.

In Beirut, Lebanon’s cats of war find peace on university campus

The American University of Beirut has long been a haven for cats abandoned in times if war or crisis, but in recent years the feline population has grown dramatically.

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

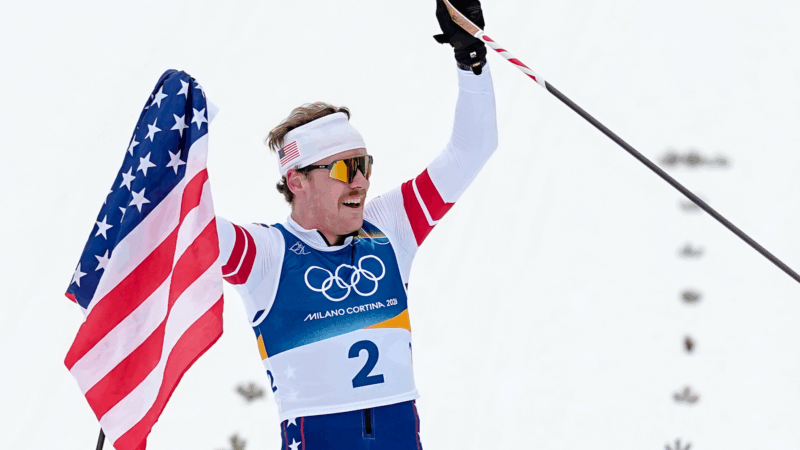

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.