Federal workers keep America’s farms healthy. What now under Trump?

Back in early March, Massachusetts Agriculture Commissioner Ashley Randle sent a letter to the new U.S. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, voicing congratulations — and a number of concerns.

Randle, a fifth-generation dairy farmer, shared that USDA’s freeze on grants — imposed before Rollins was sworn in — had left Massachusetts farmers in limbo, wondering if they’d ever be reimbursed for investments they’d made based on those grants.

She also sounded the alarm on positions that had been cut.

“The loss of USDA staff has also left Massachusetts farmers without essential resources that have long been an important part of their success,” Randle wrote, pointing to diminished staffing at the local Farm Service Agency office, which helps with loans, insurance and disaster relief.

Outside groups sued; a court order later required USDA to reinstate fired employees. But since then, the Trump administration has moved swiftly to “reorient the department to be more effective and efficient at serving the American people,” according to a USDA spokesperson.

As part of the overhaul, USDA allowed more than 15,000 employees — close to 15% of its workforce — to resign with pay and benefits through September.

Those departures have led to new concerns for Randle, including whether the federal government will be able to respond quickly in a crisis. She’s been told that many of USDA’s Area Veterinarians in Charge, who get the first call whenever a pest or disease is detected on a farm, have resigned, including the one assigned to New England.

With avian flu likely to return with the fall bird migration, and other diseases including New World screwworm and African swine fever creeping ever closer to the U.S., Randle knows U.S. farmers and ranchers, along with the U.S. food supply, could be at risk.

“Being able to be nimble and respond as quickly as possible in these types of incidents is incredibly important,” she told NPR. “It could be challenging.”

Growing fears of damage already done

Even as lawsuits challenge President Trump’s dismantling of the federal government, there are growing fears among those who work in agriculture that the exodus of thousands of employees from USDA, including more than 1,300 from the agency’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), has left American agriculture vulnerable.

“There’s no way APHIS can do its job with 1,300 fewer people,” says Kevin Shea, a 45-year veteran of USDA who led APHIS for 11 of those years. He retired in January after helping with the presidential transition.

Shea notes that over the years, APHIS employees have worked to successfully eradicate or keep at bay pests such as the boll weevil, a beetle that feeds on cotton buds, and New World screwworm, a parasite that burrows into the open wounds of animals. It’s recently resurfaced in Mexico.

He fears that progress could now be lost, with animal health technicians, epidemiologists, entomologists, wildlife biologists and many who supported them gone.

“It’ll be very hard to ever rebuild the animal health workforce and the plant health workforce because they’ve taken away so much of what made government service attractive to those people — stability, security and a sense of public mission,” Shea says.

He points to disparaging comments made by the Trump administration, including Office of Management and Budget Director Russell Vought, who once said he wanted government bureaucrats to be “traumatically affected,” to the point where they wouldn’t want to go to work.

“When they use rhetoric like that, why would you work for the government if you had another choice?” says Shea.

Helping U.S. farms maintain a competitive advantage

Given the depletion of key staff at APHIS, Shea presumes there was a lack of understanding among the new political leadership of what the agency does. He also presumes the Trump administration outsourced the reduction of the workforce to Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, “who I’m sure have no idea,” he says.

What he would want them to know is that American agriculture has been relatively free of pests and disease in recent decades thanks in large part to the work of APHIS. And that, in turn, has given the U.S. two important things: a trade advantage in relation to the rest of the world and an abundant, cheap supply of food.

It’s easy to imagine what it would look like if the U.S. were to lose significant ground on this front. Outbreaks of avian influenza in 2025 alone have resulted in the culling of more than 30 million hens, according to USDA, sending egg prices soaring. Citrus greening disease, caused by a tiny sap-sucking insect from Asia, has already wiped out much of Florida’s orange crop.

“We’re trying to save California,” Shea says. “If we don’t have a fully functioning APHIS, that’s at risk.”

And now there are concerns that New World screwworm, detected 700 miles away in Mexico, or African swine fever, now endemic in the Dominican Republic, could make their way into the U.S. and cause deadly damage to livestock.

On May 11, Rollins suspended imports of live cattle, horses and bison across the southern border to combat the spread of screwworm. Then on Tuesday, she announced a new $21 million investment to fight screwworm in Mexico.

“The investment I am announcing today is one of many efforts my team is making around the clock to protect our animals, our farm economy, and the security of our nation’s food supply,” Rollins said in a statement.

Imagining a smaller APHIS

In South Dakota, state veterinarian Beth Thompson acknowledges that there are always ways to streamline processes and make things more efficient.

Still, she worries about the sheer number of experienced veterinarians, technicians and others who have walked out the door in the span of a few short months.

“I’m really hoping that folks have captured what those people with that history and wisdom and knowledge knew,” she says.

Thompson has heard from her APHIS contacts that imports and exports and disease response will remain priorities. A USDA spokesperson has said that Rollins will not compromise the department’s critical work. But with Trump’s determination to shrink the government, Thompson assumes some programs and services will be scaled back.

She says APHIS leaders will probably need to assess whether there are diseases they can stop surveilling and devoting resources to, such as scrapie, a fatal, degenerative disease that attacks the central nervous systems of sheep and goats.

“We’re really, really close to eradicating that disease,” says Thompson. “I think that once we get through the next couple of years with that disease, that program can probably step back.”

At the moment, with employees being shifted around, she says she’s still waiting to see what the impact will be.

“I don’t think we have the final picture in place of how USDA is going to be changed and what that means for the individual farmer or rancher,” she says.

The USDA spokesperson noted that Rollins had lifted the hiring freeze on more than 50 positions “critical to the safety and security of the American people, our National forests, the inspection and safety of the Nation’s agriculture and food supply system.”

Shea questions why they let so many people go in the first place.

“It was just a completely backwards way of doing business,” he says. “And now they’re trying to backtrack that and try to figure out, gee, these are some things we really should not have done.”

In Massachusetts, Randle does believe Rollins is listening to concerns she and others have raised. She’s hopeful the USDA will take a more surgical approach moving forward, especially given all the other challenges farmers are facing, from climate change to access to labor to trade uncertainties.

“To come in and further disrupt the services and resources that farms could access, I think was really unfortunate,” says Randle. “I hope it has given some pause to the administration, to be able to look back and ask, how can we best serve our farmers and our food system stakeholders to make sure they are viable going forward?”

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

The Trump administration says food security is national security. And yet some say Trump’s depletion of the federal workforce is putting America’s farms at risk. They warn that diseases long eradicated could return, leading to higher food prices and hurdles for farm exports. NPR’s Andrea Hsu looks into those concerns.

ANDREA HSU, BYLINE: Ashley Randle is a fifth-generation dairy farmer. She also leads the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources. They’re not a huge farming state, but they do have some famous exports.

ASHLEY RANDLE: Like cranberries and seafood.

HSU: And to get those goods out of the country, they need federal employees to certify that they’re healthy. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service – or APHIS – does some of that, and also helps the state respond to pests and diseases that can wipe out crops and spread through livestock.

RANDLE: Being able to be nimble and respond as quickly as possible is incredibly important.

HSU: But Randle says the USDA veterinarian they’d call if a farmer discovered a sick cow has left, taking the government’s offer to resign with pay through September. In fact, she’s heard many of USDA’s area veterinarians in charge have quit.

RANDLE: Our key contacts, just at the state level, are no longer our contacts.

HSU: In all, some 1,300 people have resigned from APHIS since February. Those who are still there and even those who’ve opted to leave are fearful of speaking out. But Kevin Shea has been speaking out, and he’s not holding back.

KEVIN SHEA: It’s been pretty shocking.

HSU: Shea spent 45 years at USDA, most of that at APHIS. He retired in January.

SHEA: There’s no way APHIS can do its job with 1,300 fewer people. I can’t believe that hardly any of them wanted to leave.

HSU: He says many were intimidated into leaving, told they could be fired or that they’d lose their civil service protections, making them easier to fire for any reason. A USDA spokesperson told NPR APHIS’ mission-critical, front-line employees were assured their positions were safe, but Shea said people had lost trust. The feeling was the new administration did not understand what APHIS does.

SHEA: It’s essentially keeping pest and diseases out of American agriculture.

HSU: Which Shea says they’ve been pretty successful at doing over the decades.

SHEA: And that gives us a trade advantage with the rest of the world. And it also creates an abundant and, despite recent price increases in groceries, still comparatively the cheapest food supply around the world.

HSU: But you can see how that could change quickly. Avian flu continues to wipe out tens of millions of chickens every year, sending egg prices soaring. Citrus greening disease, caused by a sap-sucking insect, has already wiped out most of Florida’s orange crops.

SHEA: But we’re trying to save California. If we don’t have a fully functioning APHIS, that’s at risk.

HSU: And then there are diseases that APHIS already eradicated, like New World screwworm, a parasite that burrows into the open wounds of animals or people. It’s resurfaced in Mexico. The U.S. recently halted imports of live animals across the southern border because of this threat. Still, Shea says, there are other ways screwworm could get in.

SHEA: And so to be that close is concerning.

HSU: Those concerns are shared by Beth Thompson, South Dakota state veterinarian. But she’s still holding out to see what the impact of changes at USDA will be.

BETH THOMPSON: We’re still waiting for, well, what’s next?

HSU: She has heard that some of APHIS’ core work will continue.

THOMPSON: Import-export and also disease response will remain priorities for them.

HSU: But some programs will probably go away, she says. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins has said she’s working to make USDA more efficient and effective for the American people. She lifted the hiring freeze in order to refill some of the roles that have just been vacated. Kevin Shea wonders, where’s the efficiency in that?

SHEA: If this administration had decided they were willing to take risk with a lesser APHIS, OK, that’s your prerogative.

HSU: But he says encouraging practically every employee to quit could ultimately hurt farmers and ranchers, and the food system Americans depend on.

Andrea Hsu, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF SHYGIRL AND TINASHE SONG, “HEAVEN”)

Annual governors’ gathering with White House unraveling after Trump excludes Democrats

An annual meeting of the nation's governors that has long served as a rare bipartisan gathering is unraveling after President Donald Trump excluded Democratic governors from White House events.

Federal judge acknowledges ‘abusive workplace’ in court order

The order did not identify the judge in question but two sources familiar with the process told NPR it is U.S. District Judge Lydia Kay Griggsby, a Biden appointee.

Top 5 takeaways from the House immigration oversight hearing

The hearing underscored how deeply divided Republicans and Democrats remain on top-level changes to immigration enforcement in the wake of the shootings of two U.S. citizens.

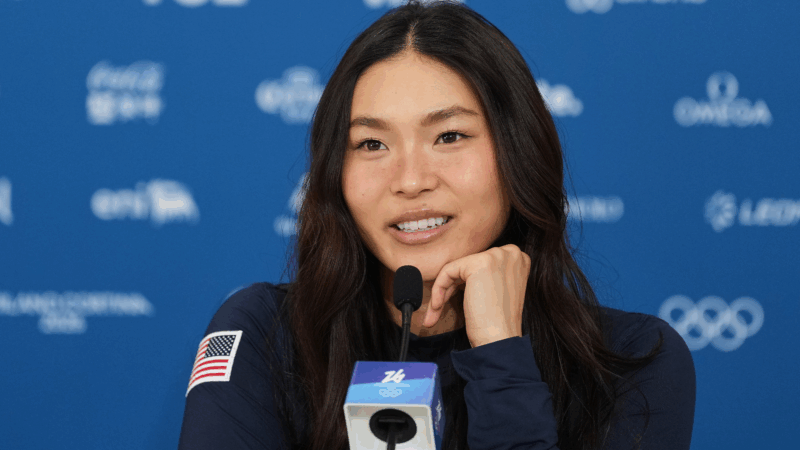

Snowboarder Chloe Kim is chasing an Olympic gold three-peat with a torn labrum

At 25, Chloe Kim could become the first halfpipe snowboarder to win three consecutive Olympic golds.

Pakistan-Afghanistan border closures paralyze trade along a key route

Trucks have been stuck at the closed border since October. Both countries are facing economic losses with no end in sight. The Taliban also banned all Pakistani pharmaceutical imports to Afghanistan.

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.