Evergrande’s delisting in Hong Kong: key facts to know

Shares in China Evergrande were removed from the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on Monday, marking another step in the retreat of the giant real estate developer whose downfall contributed to a prolonged crisis in China’s property market.

Evergrande’s creditors are still working to wind up debts that amounted to more than $340 billion. Once China’s second-largest developer, it ran into trouble when Chinese regulators cracked down several years ago on what they deemed to be excess borrowing by developers.

That caused dozens of property companies to default on their debts, triggering a downturn in the property market that is still dragging on the world’s second-largest economy.

Here’s what to know about Evergrande:

The delisting of a one-time leader in China’s property market

The Hong Kong Exchange said Monday that Evergrande’s shares were delisted as of Monday morning, as expected. The shares were last traded on January 29, 2024, and then suspended after a court in Hong Kong ordered liquidation of the company when it failed to provide a viable debt restructuring plan.

Rules of the exchange stipulate that a company’s share listing may be canceled if trading in its securities is suspended for 18 straight months.

Evergrande’s role in China’s property crisis

After years of warnings that led to global rating agencies cutting the Chinese government’s credit rating in 2017, the ruling communist party cracked down on real estate debt in 2020. It imposed controls known as “three red lines” that prohibited heavily indebted developers like Evergrande from borrowing more to pay off bonds and bank loans as they matured.

Fears of a possible Evergrande default in 2021 rattled global markets, but they eased after the Chinese central bank said its problems were contained and Beijing would keep credit markets functioning. Evergrande was one of the biggest of many developers that failed to repay their creditors.

Chinese home buyers often pay up front for apartments before they’re even built. The credit crunch for Evergrande and other developers led them to suspend construction, leaving many projects in limbo. The slowing of home purchases and building rippled throughout the economy, hitting demand for construction materials, appliances and even vehicles at a time when China was also contending with disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since most Chinese families have their wealth tied up in property, the anemic housing market has been a major factor crimping consumer spending.

The property downturn grinds on

There has been some recovery in the housing sector, but home prices and investment have continued to fall.

Before the crackdown on borrowing, real estate accounted for some 20% of China’s economy. When spending on steel and copper for construction, furniture and other related purchases was added in, estimates of its share of the economy rose to about a third.

China’s leaders have sought to get developers to finish projects and deliver apartments that already were paid for, providing billions in lending and subsidies. They’ve encouraged local governments to buy up excess apartments to serve as affordable housing, and relaxed down payment and mortgage requirements.

They’ve also lifted many restrictions on purchases of homes for investment purposes in major cities, a move that analysts at HSBC Global Investment Research described as “surprising” as they came earlier than expected.

Sales and home prices were expected to fall further in August, they said in a recent report.

“We think it’s a positive change showing government’s enhanced proactiveness in rolling out measures, which will help strengthen market confidence and address the concern on stimulus being too late,” it said.

Evergrande’s status

Evergrande, headquartered in southern China’s Shenzhen, near Hong Kong, was founded by entrepreneur Hui Ka Yan, who is also known as Xu Jiayin, in 1996. Its ascent and decline have mirrored the boom and bust in China’s property market after housing reforms allotted apartments built by state-owned industries to employees, creating a nation of home owners.

The company’s shares were listed in Hong Kong in 2009.

Evergrande filed for Chapter 15 bankruptcy protection in New York City in 2023, but that case was later withdrawn. Although a Hong Kong court ordered a winding up of the company’s debts, more than 90 percent of its assets are on the Chinese mainland, making it difficult to enforce repayment to its creditors.

Its liquidators said in a recent progress report that they had received debt claims totaling $45 billion as of Jul. 31, much higher than the some $27.5 billion of liabilities disclosed in December 2022, and that the new figure was not final. They also had taken control of more then 100 companies within the group with collective assets valued at $3.5 billion as of Jan. 29, 2024.

So far, about $255 million worth of assets have been sold, the liquidators said, calling the realization “modest.”

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.

In this Icelandic drama, a couple quietly drifts apart

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason weaves scenes of quiet domestic life against the backdrop of an arresting landscape in his newest film.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.

They’re cured of leprosy. Why do they still live in leprosy colonies?

Leprosy is one of the least contagious diseases around — and perhaps one of the most misunderstood. The colonies are relics of a not-too-distant past when those diagnosed with leprosy were exiled.

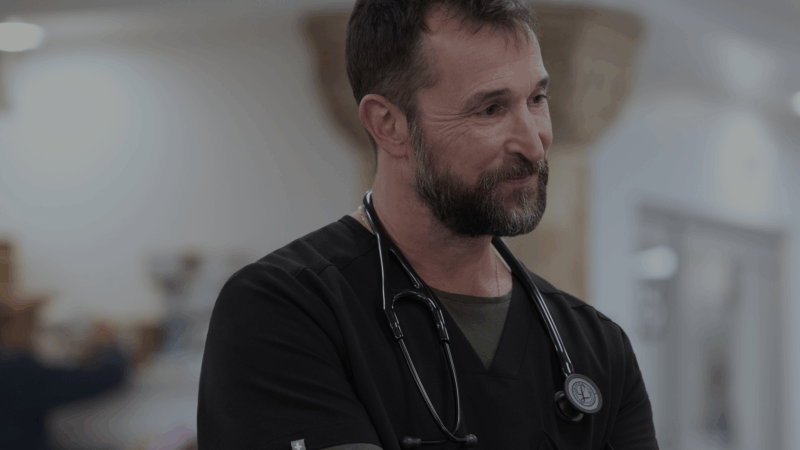

This season, ‘The Pitt’ is about what doesn’t happen in one day

The first season of The Pitt was about acute problems. The second is about chronic ones.