Eli Lilly sues companies selling alternative versions of its weight loss drug

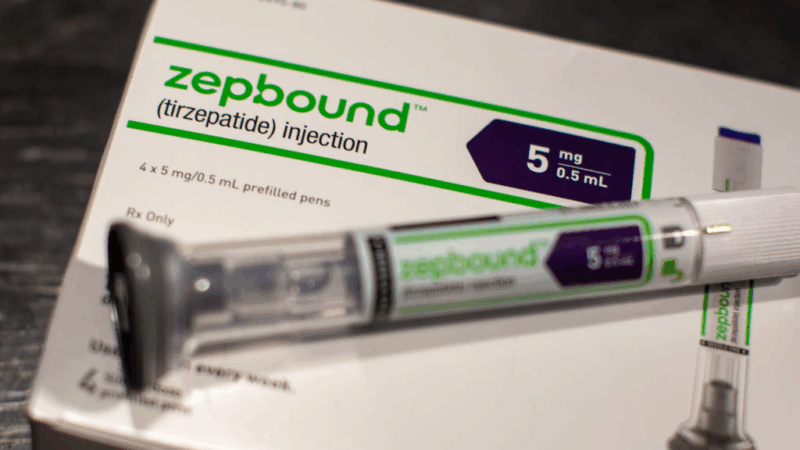

Eli Lilly, the drugmaker behind the blockbuster weight loss drug Zepbound, is suing four telehealth companies for allegedly selling illegal copies of the drug made by compounding pharmacies.

Compounded drugs aren’t generics. Rather, they are essentially copies that are allowed to be made by special pharmacies called compounding pharmacies during drug shortages. Tirzepatide, the active ingredient in Lilly’s Zepbound and Mounjaro for Type 2 diabetes, was in shortage for two years until Dec. 19, 2024. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration required an end to making the copies by mid-March, but pharmacies could sell stock already produced until it ran out or expired. And compounders can generally make custom drugs for patients with a doctor’s prescription as they do for patients with allergies to certain preservatives in medications, for example.

During the Zepbound shortage, compounding pharmacies filled the gap for patients who couldn’t find the brand name drug in their pharmacies and patients who didn’t have insurance coverage for the drug and couldn’t afford Zepbound sticker price of more than $1,086.37 a month. For comparison, compounded tirzepatide sells for as little as $99 a month.

Now, the tirzepatide shortage is over and deadlines for producing new copies of tirzepatide have passed, Eli Lilly is cracking down.

“Anyone continuing to sell mass compounded tirzepatide is breaking the law and deceiving patients,” Lilly said in a company statement sent to NPR. “We will continue to take action to stop those who threaten patient safety and urgently call on regulators and law enforcement to do the same.”

Eli Lilly filed lawsuits against compounding pharmacies earlier this month. Now, it has turned its attention to telehealth companies selling compounded tirzepatide. On Wednesday, Lilly filed complaints against Mochi Health, Willow Health, Fella Health and Delilah, and Henry Meds.

According to one complaint, Mochi allegedly switched its patients to compounded tirzepatide with different additives, like niacinamide. The complaint also alleges they switched patients over to different doses than those offered by Eli Lilly. These changes were made “at least five times in just eight months,” alleges the complaint, to enable Mochi to keep selling compounded tirzepatide.

The existing law prohibits compounders from making “essentially” a copy of an existing commercially available drug.

Mochi representatives did not respond to requests for comment.

Lilly’s complaint against Henry Meds alleges the telehealth company improperly referenced Lilly’s approved drugs and clinical trials on its website in order to sell more compounded versions. Henry Meds and Fella Health are also accused of selling tirzepatide in pill form, which has never been approved by the FDA. “Fella even tells patients that its untested oral drug is better than Lilly’s approved medicines,” Lilly’s complaint against Fella alleges.

And the complaint against Willow Health asserts that Willow falsely claimed to have developed the first “cosmetic” GLP-1. “FDA has never approved any form of tirzepatide for cosmetic weight loss,” Lilly’s complaint alleges, adding that Lilly makes the only FDA-approved tirzepatide.

Henry Meds, Fella Health and Willow Health did not respond to NPR’s requests for comment.

On April 1, Eli Lilly sued two compounding pharmacies: Strive and Empower. Strive tells NPR it will fight back, and Empower says in a statement posted to its website, “We stand by our mission, and the patients and providers who depend on it.”

Scott Brunner, the CEO of the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding, an advocacy group for compounding pharmacies, declined to comment on the specific suits or companies. However, in an email to NPR, he explained that compounders only produce drugs when a prescriber sends a prescription.

“I fear there is not a bright line on this issue of corporate practice of medicine vs. legitimate customization of a drug based on the judgment of a prescriber who has actually interacted with a patient,” he wrote. “FDA guidance clearly authorizes the latter, but the former is to a certain degree in the eye of the beholder. In these new Lilly lawsuits, [it] looks like the beholder will be a Federal judge.”

The FDA creates a quicker path for gene therapies

The Food and Drug Administration aims to evaluate treatments for rare diseases based on plausible evidence that they would work — without requiring a clinical trial first.

BAFTAs apologize after guest with Tourette syndrome uses racial slur during ceremony

A man with Tourette syndrome shouted a racial slur and other offensive remarks during the BAFTA awards ceremony Sunday. The BBC did not edit out his outbursts in its delayed broadcast.

‘Everything was in pieces:’ Lindsey Vonn describes grueling surgery on broken leg

In a recent video, the Olympic skier credits her surgeon with saving her leg from potential amputation.

A new lawsuit alleges DHS illegally tracked and intimidated observers

Observers watching federal immigration enforcement in Maine who were told by agents they were "domestic terrorists" and would be added to a "database" or "watchlist" are now part of a new federal class action lawsuit.

Kate Hudson on regret, rom-coms and finding a role that hits all the notes

Hudson always wanted to sing, but feared it would derail her acting career. Now she's up for an Oscar for her portrayal of a hairdresser who performs in a Neil Diamond tribute band in Song Sung Blue.

A powerful winter storm is roiling travel across the northeastern U.S.

Forecasters called travel conditions "extremely treacherous" and "nearly impossible" in areas hit hardest by the storm, and air and train traffic is at a standstill in many parts of the region.