DOGE says it needs to know the government’s most sensitive data, but can’t say why

Fewer than 50 people have access to Social Security Administration databases containing hundreds of millions of people’s private financial and personal information.

But only one also has access to the government’s human resources and student loan files.

Akash Bobba is one of many Department of Government Efficiency staffers who have embedded in federal agencies the last few months with virtually unfettered access to the sensitive, compartmentalized sources of data collected by the government. The team, which is steered by billionaire Elon Musk, says it’s scouring government records for signs of waste, fraud and abuse.

Bobba is also one of many DOGE employees who, according to several federal judges, were inappropriately given that access in violation of privacy laws and without proper training to handle the personally identifiable information the agencies collect.

In one order last week blocking DOGE’s access to Social Security data, U.S. District Judge Ellen Lipton Hollander of Maryland said the government “never identified or articulated even a single reason for which the DOGE Team needs unlimited access to SSA’s entire record systems, thereby exposing personal, confidential, sensitive, and private information that millions of Americans entrusted to their government.”

Instead of a more narrow approach to data access and work to “modernize the system and uncover fraud,” Hollander wrote that DOGE’s unprecedented access to protected data “is tantamount to hitting a fly with a sledgehammer.”

An NPR review of thousands of pages of records across more than a dozen lawsuits in federal court finds an alarming pattern across agencies, where DOGE has given conflicting information about what data it has accessed, who has that access, and most importantly — why.

“No need to know”

When President Trump signed an order creating the DOGE initiative, it directed agencies to create dedicated teams that would have “full and prompt access to all unclassified agency records, software systems, and IT systems” that would also “adhere to rigorous data protection standards.”

Numerous court filings and affidavits paint a picture of agencies rushing to give DOGE access without accompanying rigor of protecting data or documenting the scope of its work.

On Monday, a federal judge in Maryland temporarily halted DOGE from accessing data of millions of union members in a lawsuit against the Office of Personnel Management, the Treasury Department and Education Department after finding the agencies shared private information with DOGE affiliates “who had no need to know the vast amount of sensitive personal information to which they were granted access.”

“No matter how important or urgent the President’s DOGE agenda may be, federal agencies must execute it in accordance with the law,” Judge Deborah L. Boardman wrote. “That likely did not happen in this case.”

In the Social Security Administration lawsuit, Hollander found several DOGE staffers “were granted access to SSA systems before their background checks were completed or their inter-agency detail agreements were finalized.“

One of those is Bobba, who was given access to the master data warehouse at SSA that includes the Master Beneficiary Record, Supplemental Security Record and Numident files containing “extensive information about anyone with a social security number,” according to filings in the case.

According to a memorandum of understanding detailing Bobba’s work with SSA, the Office of Personnel Management and Education Department that was improperly redacted by OPM, Bobba agreed to do any work on Social Security data from the agency headquarters.

But an affidavit from former SSA chief of staff Tiffany Flick said that Bobba was working off-site from OPM where other people “may have also had access to this protected information,” Flick wrote.

Not even lawyers for the government can account for when and how DOGE staffers received access to sensitive databases. In a Labor Department lawsuit, Judge John D. Bates notes that “defendants themselves acknowledge inconsistencies across their evidence” regarding DOGE.

Marko Elez, a DOGE employee who resigned from his post at the Treasury Department in early February after racist social media posts resurfaced, “sent an email with a spreadsheet containing PII to two United States General Services Administration officials,” according to an audit of his email account submitted in one court filing.

Government lawyers said Elez was “erroneously” and “mistakenly” given the ability to change data on Treasury’s Secure Payment System, which a judge said demonstrates DOGE access was “rushed and undertaken by political pressure.”

In a ruling blocking DOGE access to Treasury systems, Judge Jeannette Vargas warned that “a real possibility exists that sensitive information has already been shared outside of the Treasury Department, in potential violation of federal law.”

Congress warned against this — a half-century ago

When Congress passed the Privacy Act of 1974, lawmakers expressed concerns about personal information amassed in digital databases by the “omnivorous fact collectors” of federal agencies.

During the debate about the bill, Arizona Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater was worried about the possibility “that every detail of our personal lives can be assembled instantly for use by a single bureaucrat or institution.”

“I hope that we never see the day when a bureaucrat in Washington or Chicago or Los Angeles can use his organization’s computer facilities to assemble a complete dossier or all known information about an individual,” Republican Sen. Charles Percy said.

Fifty years later, the Department of Government Efficiency effort headed by Musk appears to be doing just that, bypassing the Privacy Act, agency security protocols and training for handling the most sensitive data maintained by federal agencies.

The White House did not respond to questions about DOGE following privacy laws, or whether Americans should be concerned about the level of DOGE’s access.

The federal government maintains a large amount of sensitive data, from health records of veterans and Medicare recipients to troves of information about companies being investigated by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the National Labor Relations Board.

The rapid insertion of DOGE employees into the system is raising alarm bells for privacy and security advocates.

“The government has also repeatedly failed to articulate a clear purpose for the unprecedented access it seeks to deeply sensitive information, and why the data it wants access to is necessary for that purpose,” said Kristin Woelfel, a lawyer with the nonprofit Center for Democracy and Technology. “If the government cannot answer those questions, then DOGE has no business accessing that data.”

“Part of what is unnerving and is scary both to companies whose data is involved and also Americans whose most sensitive financial information is at risk, is that we don’t know what they’re doing,” former CFPB chief technologist Erie Meyer previously told NPR.

Anne Weismann, a George Washington University Law School professor who focuses on government accountability and transparency, said DOGE and its employees have control over a “staggering” amount of data about Americans.

“It’s so ironic because Trump supporters are so worried about ‘Big Brother’ and government, and they are allowing this entity to amass that data,” Weismann said. “I mean, I don’t think there’s another entity in the federal government that collectively has access to that kind of data.”

Weismann is also outside counsel for the nonprofit Project On Government Oversight, which is suing DOGE over access to records about how it operates.

Last week, Trump signed an executive action that appears to continue to push agencies toward “eliminating information silos” and sharing more sensitive data across federal agencies, including ensuring that the government has “unfettered access to all unemployment data and related payment records.”

It encourages federal agency leaders to find ways to rescind existing regulations and guidance about information sharing within and between agencies — with no mention of privacy or data security.

US launches new retaliatory strike in Syria, killing leader tied to deadly Islamic State ambush

A third round of retaliatory strikes by the U.S. in Syria has resulted in the death of an Al-Qaeda-affiliated leader, said U.S. Central Command.

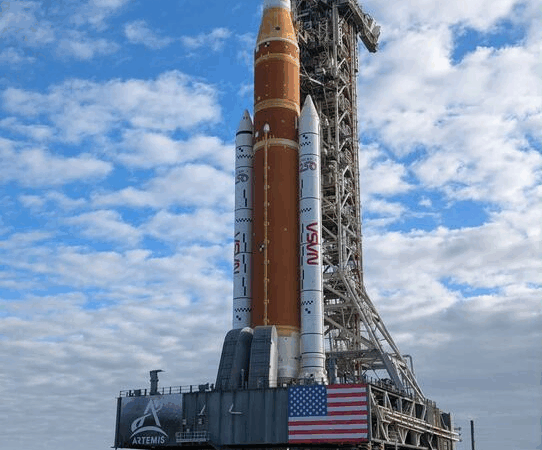

NASA rolls out Artemis II craft ahead of crewed lunar orbit

Mission Artemis plans to send Americans to the moon for the first time since the Nixon administration.

Trump says 8 EU countries to be charged 10% tariff for opposing US control of Greenland

In a post on social media, Trump said a 10% tariff will take effect on Feb. 1, and will climb to 25% on June 1 if a deal is not in place for the United States to purchase Greenland.

‘Not for sale’: massive protest in Copenhagen against Trump’s desire to acquire Greenland

Thousands of people rallied in Copenhagen to push back on President Trump's rhetoric that the U.S. should acquire Greenland.

Uganda’s longtime leader declared winner in disputed vote

Museveni claims victory in Uganda's contested election as opposition leader Bobi Wine goes into hiding amid chaos, violence and accusations of fraud.

Opinion: Remembering Ai, a remarkably intelligent chimpanzee

We remember Ai, a highly intelligent chimpanzee who lived at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University for most of her life, except the time she escaped and walked around campus.