Do neck cooling fans really help you beat the heat?

On a late July morning, the sun is already broiling the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The air is so humid, even a loose shirt quickly turns into a sticky mess.

Later, the heat index will top out around 103 degrees, turning the walk between air-conditioned museums into a scorching trek. I’m on my bike, in the hottest part of the summer tourist season, on a mission: to find visitors who are trying to beat the heat with an odd-looking gadget that’s gained in popularity in recent years. It doesn’t take long.

“These are amazing,” says Christa Seger, who sits with three of her kids in the shade near the Washington Monument.

She holds up a cooling neck fan. It looks like a space-age horseshoe, but resting on your neck, it uses dozens of vents to blow air toward your ears and head. Some models — like Seger’s — also have metal panels, to help dissipate heat.

“I can’t believe how cold they get,” says Seger, who’s visiting from Denver.

Seger bought two fans for about $25 each a few days ago, back in Colorado.

“They last somewhere between 4 to 6 hours on a full charge,” she says. Thinking the fans might help her daughter as they march from Smithsonian museums to historic buildings — and the occasional ice cream truck — she brought a battery pack to keep the fans juiced up.

“She loved it yesterday. It really helped her,” Seger says.

Some of these fans can cost hundreds of dollars. But I’m trying out a very basic model today. As it powers on, air starts whooshing past my ears and neck. It feels like a nice breeze. But is it really doing anything to cool me?

How the neck fans work

Consider the main strategy our bodies use to cool down: sweating.

“The heat of vaporization gets pulled from that sweat into the atmosphere,” says Dr. Adam Watkins of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. “So you actually are losing heat that way.”

But that’s not always enough. Watkins says the emergency room where he works is seeing 25% more heat exposure cases this summer than last year — a trend he says has been rising over the past decade.

Intense heat waves are one reason why people might look to a personal cooling fan. But there are limits to how well they can work.

“The biggest thing is being able to evaporate the sweat off your body,” says Cecilia Kaufman, director of occupational safety for the Korey Stringer Institute at the University of Connecticut.

In theory, a fan can boost your body’s evaporative cooling process by speeding the flow of air over your skin.

“The problem is when it’s hot and humid, the sweat does not evaporate as quickly off your skin,” Kaufman says. “So that takes away your body’s ability to really cool.”

Surface area is key to effective cooling

For evaporation to work well, it helps to expose lots of skin.

“The best way to cool down would be basically to take all your clothes off, expose the entire body to the air and let all of the sweat evaporate,” says Chris Tyler, a researcher in environmental physiology at the University of Roehampton in London. “But you’d get arrested,” he adds with a laugh, “so that’s not a recommendation.”

In contrast, a neck fan can only affect a small part of your body. It might feel nice to use one, even if it’s blowing humid air. In part, that’s because there are a lot of thermal receptors on the face and neck, making them very sensitive to heat.

In general, we shouldn’t view these neck fans as a type of treatment, Tyler says.

“It’s a bit like playing sport with a painkilling injection,” he says. “The issue is still there. It’s just that you can’t detect it for a little bit.”

As a result, Tyler and Kaufman say, the small fans likely do more to make us feel cooler rather than actually lowering our body temperature — which could raise the risk of someone over-exerting themselves without realizing how the heat is affecting them.

But they also note that research is ongoing into improving ways of cooling the head and neck, as well as using cooling garments like hats and neck gaiters in hot environments.

Taking a neck fan for a test whirl

Down at the National Mall, I’m a bit skeptical when I first put my fan on. After all, the midday air is still and scorching. The flags that ring the Washington Monument’s base are drooping and listless. (I feel you, flags.)

But as it starts to blow air on my ears and head, this little doodad does seem to make my time riding and walking a bit more bearable. I’m aware that I might look like an extra from a low-budget sci-fi movie with this thick, plastic device looped around my neck. But it doesn’t feel too heavy or obstructive. And while I don’t have long hair (or, let’s be real, much hair of any type), it’s worth noting that many of the fans are bladeless, so they’re less likely to get entangled.

I roll down past the Reflecting Pool to the Lincoln Memorial. Along the way, I notice that when the neck fan is set to maximum power, the sound of the motor can be a distraction. At the bottom of the memorial steps, I run into Jeffrey Pagulong, who’s visiting from Boston. He and his son Christof, 12, both wear neck fans.

“It’s really hot,” Pagulong says, standing in the blazing sun. “And wearing this fan kind of helps a lot, it cools down your head, so it helps” to ease the heat from walking, he adds.

I ask if the sound bothers him.

“The noise is OK. You can hear the fan, but it’s fine. The noise is much better than the heat, you know? I can take the noise, but not the heat.”

In my informal survey of the Mall, I spot more people using old-fashioned parasols than newfangled fans. It turns out a street vendor has been doing brisk business, selling yellow and red umbrellas for $10. One customer was Galilee Maldonado, 16, visiting from Texas.

“I bought it yesterday from a lady, but I really liked it,” she says.

Like a neck fan, the parasol might not do much to lower her core temperature. But it’s making Maldonado, who says she was surprised by the heat in Washington, feel better.

“It’s helping me cope with this weather,” she says.

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Have you ever noticed people using those odd-looking gadgets to fight the summer heat, like the little fans that sit around their necks and blow air? The idea is it helps cool you down, but does it work? NPR’s Bill Chappell is on a mission to find out.

BILL CHAPPELL, BYLINE: On a late July morning, the sun is already broiling the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The air’s so humid, even a loose shirt quickly turns into a sticky mess. I’m looking for people who are using those neck-cooling fans to get some relief.

CHRISTA SEGER: Oh, these are amazing.

CHAPPELL: Christa Seger is sitting with her kids in the shade near the Washington Monument. She holds up a fan. It looks like a thick plastic horseshoe that hangs around your neck and has dozens of vents that blow air toward your head.

SEGER: I can’t believe how cold they get.

CHAPPELL: Seger is visiting from Denver where she bought two fans a few days ago. They cost about $25 and can run for four to six hours. Her daughter’s been wearing one as they walk to museums and ice cream trucks.

SEGER: We have never used them before, and she loved it yesterday.

CHAPPELL: Some of these devices can cost hundreds of dollars, but I’m trying out a basic model today.

(SOUNDBITE OF FANS BLOWING)

CHAPPELL: Air starts whooshing past my ears and neck. It feels like a nice breeze. But is it really doing anything? I put that question to Chris Tyler, a researcher in environmental physiology at the University of Roehampton in London.

CHRIS TYLER: They’re doing something. What they are doing is that they’re making the wearer feel cooler.

CHAPPELL: The key word there is feel. Tyler says a small neck fan can make someone feel more comfortable without actually doing much to lower their body temperature. But because we have lots of thermal receptors in our neck and face, it can feel nice. But Tyler says…

TYLER: This is not a treatment. It’s a bit like playing sport with a painkilling injection. The issue is still there. It’s just that you can’t detect it for a little bit.

CHAPPELL: Think of the main strategy our bodies use to cool down.

CECILIA KAUFMAN: The biggest thing is being able to evaporate the sweat off your body.

CHAPPELL: That’s Cecilia Kaufman, director of occupational safety for the Korey Stringer Institute at the University of Connecticut.

KAUFMAN: The problem is when it’s hot and humid, that sweat does not evaporate as quickly off your skin.

CHAPPELL: You might feel more comfortable using a neck fan, even if it’s blowing humid air, but it only affects a small area of skin. Tyler says the most important thing is trying to cool as much of the body’s surface area as possible.

TYLER: So the best way to cool down would be basically to take all your clothes off, expose the entire body to the air and let all of the sweat evaporate. But you’d get arrested, so that’s a that’s not a recommendation.

CHAPPELL: Back on the National Mall, we’re all sweating through our clothes. The sun is blazing as I bump into Jeffrey Pagulong and his son Christof at the Lincoln Memorial. They’re visiting from Boston, and both are wearing neck fans.

JEFFREY PAGULONG: It’s kind of, like, 95 degrees right now, and wearing these fans kind of helps a lot. It cools down your head. So it helps.

CHAPPELL: You can probably hear the fan there in the background. So I ask, is the noise annoying?

J PAGULONG: Yeah, you can hear the fan, but it’s fine. It’s better to have it. I mean, the noise is much better than the heat, you know?

CHRISTOF PAGOLONG: Yeah.

CHAPPELL: As we speak, the heat index is maxing out at around 103 degrees. So yeah, right now, anything seems better than feeling the heat. Bill Chappell, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF A.V. HAMILTON AND HIJNX SONG, “DOWN!”)

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

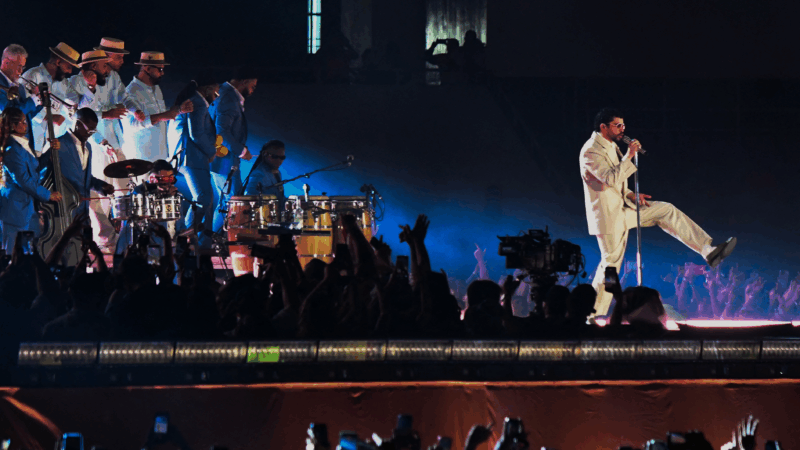

What you should know about Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

Will the Puerto Rican superstar bring out any special guests? Will there be controversy? Here's what you should know about what could be the most significant concert of the year.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

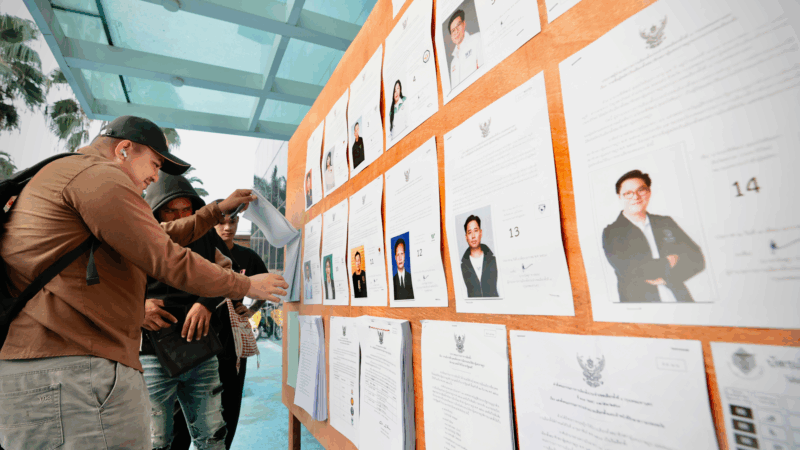

Thailand counts votes in early election with 3 main parties vying for power

Vote counting was underway in Thailand's early general election on Sunday, seen as a three-way race among competing visions of progressive, populist and old-fashioned patronage politics.

US ski star Lindsey Vonn crashes in Olympic downhill race

In an explosive crash near the top of the downhill course in Cortina, Vonn landed a jump perpendicular to the slope and tumbled to a stop shortly below.