Chile’s Indigenous fishermen say the salmon industry threatens their way of life

PUERTO NATALES, Chile — Out beyond Isla Focus, a bare island in the fjords an hour off the coast of Puerto Natales, southern Chile, the waves pick up and the Calipso rocks alarmingly from side to side.

Reinaldo Caro is the swarthy captain of the tiny fishing vessel, and he has spotted something amid the pristine Patagonian woodland high above the shoreline: a single, white-bark tree.

“There!” he exclaims suddenly, his thick eyebrows lifting as his face softens into a broad smile. “That’s where I was born.”

“And then that’s what I’m fighting against,” he says, tracing a path down the hillside with a finger, fixing it on a pontoon floating directly below his birthplace.

It belongs to one of the many salmon farms that dot the fjords, although from the surface, there isn’t much to see. A control room sits alongside several floating walkways.

The salmon farming industry operates along great swaths of Chile’s coastline, from the center of the country and down through Patagonia.

And Caro, 78, decries the effect it has had on his ancestral home.

He is one of the very last Kawésqar fishermen sailing these fjords, one of the seminomadic Indigenous peoples who navigated the channels for millennia in carved wooden canoes.

Today, there are fewer than 1,000 Kawésqar left.

“There are loads of these farms,” Caro says over the throb of the Calipso’s diesel engine.

With each pontoon that passes by, he reels off the name of the company which operates it and then the moniker he has for each tiny bay nearest to the farm.

In some, he says, Kawésqar would cut down the trees to make their canoes. In others, huddles of cormorants gather on the black sand beaches, and sea lions bark from the rocks.

“From up here it looks beautiful and pristine, like a mirror, but down there it’s a different story,” Caro explains. “The contamination is on the seabed — it comes from the feces and medication they give them.”

“Maybe 30 or 35 years ago, this place was totally pristine. Now we’re up to our necks in it,” he says bitterly.

In 2024, the United States, Japan and Brazil were the major markets for Chilean salmon, and more than half of the salmon available in U.S. supermarkets came from Chile.

After copper, the backbone of the Chilean economy accounting for more than half of the gross domestic product, salmon products are, albeit distantly, the country’s second-largest export.

Last year, $6.3 billion worth of salmon was sent abroad, according to the Chilean Salmon Council. One-quarter of the world’s salmon is farmed in Chile. Only Norway exports more.

Yet the fish are not native to these waters, and fishermen like Caro say that they are damaging Chilean ecosystems.

“I think it’s important to talk about how vulnerable these ecosystems are in general to change,” says marine biologist Claudio Carocca, who has written extensively about the effects of the salmon industry .

“In this case, the changes affected by human activity range from installing pontoons with their steel, plastic, ropes and lights; to the nonnative fish species introduced, and the chemicals and food injected to help them grow,” he says.

The Chilean Salmon Council, which represents the largest salmon farming companies in the country, declined NPR’s request for comment on the issues raised by the local community. The council’s website says salmon farming has the potential to provide “a healthy and sustainable source of protein” for growing global demand for quality foods. “We believe this can be achieved responsibly, caring for the environment and ensuring the highest environmental, social and animal welfare standards,” it says. The website also says the industry has worked to reduce the use antimicrobials.

Conditions in Chile are seen as ideal for salmon farming, with the first attempts to introduce salmon dating as far back as the 19th century.

In 1969, an agreement between Japan and Chile’s national fishing agency saw Pacific salmon formally introduced, bringing Dutch and Japanese companies into the country.

The national fishing service was then formed in 1976 under the dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet, and production skyrocketed from the mid-1980s.

A salmon usually reaches its commercial size and weight at 4 years old, but in a farm this is cut to 10 to 14 months.

Reinaldo Caro’s daughter, Leticia Caro, grew up sailing these fjords with her father, who has always worked at sea.

She was 6 years old when she came out fishing with her father for the first time, where she’d help clean the fish and disentangle the nets.

“I think that things can be done differently, because salmon farming will never be sustainable,” she says.

“If the industry hadn’t moved into our home, the Kawésqar would probably still be living on these shores the way we always did. It’s vital that after thousands of years in these channels, the balance is maintained.”

Chile’s salmon industry has long been criticized for polluting the fjords and coastline, triggering record algal blooms, regular escapes that threaten native wildlife, as well as a heavy use of antimicrobials.

Salmon farms pump more than 350 metric tons of antibiotics into the sea each year. Given these quantities, the nongovernmental watchdog group Seafood Watch recommends that people avoid eating Chilean salmon unless it’s purchased from a certified, sustainable business.

However, legislation is in its final stage on its passage through Chilean congress that would deem salmon farming and the Kawésqar people’s traditional way of life in the area “totally incompatible,” halting the expansion of the industry.

Politicians are also debating whether to freeze or limit concessions on new farms in the southernmost waters.

“They should go,” says Carocca. “But it’s not so simple — lots of people depend on the industry for work. What we need to ask ourselves is what is left when the farms move on? What will those people do?”

“Because we have already seen nearly 50 years of a model which doesn’t work, based on an exotic species which isn’t from here, and which requires so much to be added to the water for it to work.”

“It generates billions of dollars, but how many billions is all this destruction worth?”

Federal judge acknowledges ‘abusive workplace’ in court order

The order did not identify the judge in question but two sources familiar with the process told NPR it is U.S. District Judge Lydia Kay Griggsby, a Biden appointee.

Top 5 takeaways from the House immigration oversight hearing

The hearing underscored how deeply divided Republicans and Democrats remain on top-level changes to immigration enforcement in the wake of the shootings of two U.S. citizens.

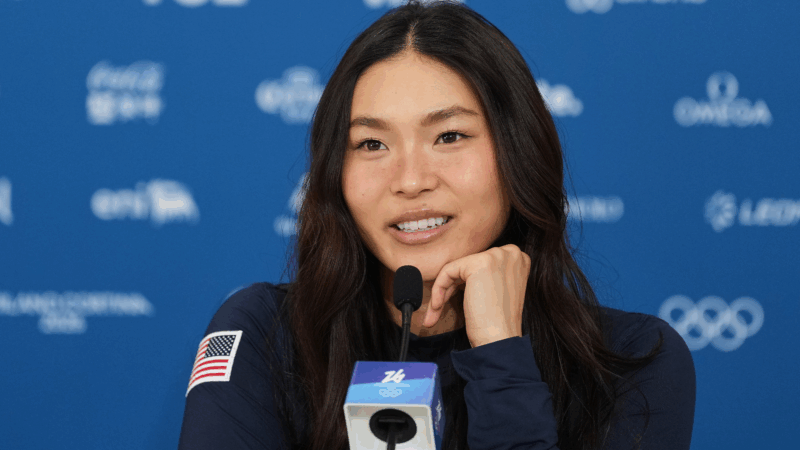

Snowboarder Chloe Kim is chasing an Olympic gold three-peat with a torn labrum

At 25, Chloe Kim could become the first halfpipe snowboarder to win three consecutive Olympic golds.

Pakistan-Afghanistan border closures paralyze trade along a key route

Trucks have been stuck at the closed border since October. Both countries are facing economic losses with no end in sight. The Taliban also banned all Pakistani pharmaceutical imports to Afghanistan.

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

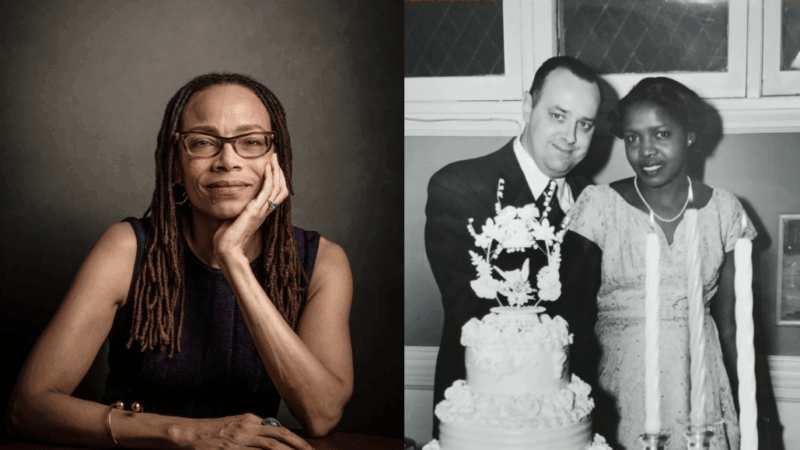

A daughter reexamines her own family story in ‘The Mixed Marriage Project’

Dorothy Roberts' parents, a white anthropologist and a Black woman from Jamaica, spent years interviewing interracial couples in Chicago. Her memoir draws from their records.