Can this nasal spray slow down Alzheimer’s? One couple is helping scientists find out

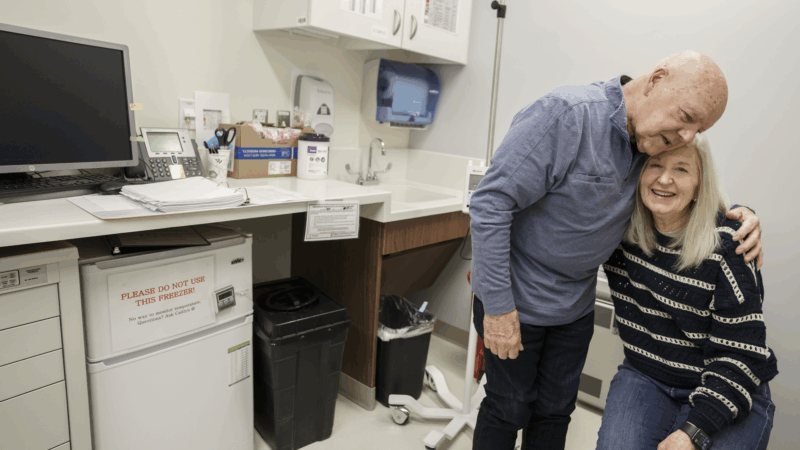

Joe Walsh, 79, is waiting to inhale.

He’s perched on a tan recliner at the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. His wife, Karen Walsh, hovers over him, ready to depress the plunger on a nasal spray applicator.

“One, two, three,” a nurse counts. The plunger plunges, Walsh sniffs, and it’s done.

The nasal spray contains an experimental monoclonal antibody meant to reduce the Alzheimer’s-related inflammation in Walsh’s brain.

He is the first person living with Alzheimer’s to get the treatment, which is also being tested in people with diseases including multiple sclerosis, ALS and COVID-19.

And the drug appears to be reducing the inflammation in Walsh’s brain, researchers report in the journal Clinical Nuclear Medicine.

“I think this is something special,” says Dr. Howard Weiner, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham who helped develop the nasal spray, along with its maker, Tiziana Life Sciences.

Whether a decrease in inflammation will bring improvements in Walsh’s thinking and memory, however, remains unclear.

The experimental treatment is part of a larger effort to find new ways to interrupt the cascade of events in the brain that lead to Alzheimer’s dementia.

Two drugs now on the market clear the brain of sticky amyloid plaques, clumps of toxic protein that accumulate between neurons. Other experimental drugs have targeted the tau tangles, a different protein that builds up inside nerve cells.

But fewer efforts have tried to address inflammation, a sign of Alzheimer’s that becomes more pronounced as the disease progresses.

A diagnosis and a quest for care

Once Joe Walsh has finished inhaling the experimental medication, he gets a cognitive exam from Dr. Brahyan Galindo-Mendez, a neurology fellow.

“Can you tell me your name please,” Mendez asks. “What’s your name?”

After a pause, Walsh answers: “Joe.”

“And who is with you today?” Mendez says, glancing toward Walsh’s wife, Karen.

“We’ll do that,” Walsh replies.

“What’s her name?” Mendez persists.

“Her name,” Walsh echoes. “That’s her name. That’s my wife.”

Walsh is unable to put a name to the woman he’s been married to for 36 years.

Karen Walsh began to notice a change in her husband back in 2017.

“He was struggling to find the right words to complete a thought or a sentence,” she says.

The couple went to a primary care doctor, who said that if Walsh turned out to have Alzheimer’s, he should enter a research study in hopes of getting one of the latest treatments. Then the doctor referred Walsh to a neurologist.

In 2019, a PET scan revealed extensive amyloid plaques in Walsh’s brain, confirming the diagnosis.

“As much as I was in shock,” Karen Walsh says, “the words were ringing in my head: ‘ask for the research.'”

So she began looking for a clinical trial. But in 2020, COVID arrived in the U.S., shuttering hundreds of research studies. By the time the pandemic subsided, Walsh’s Alzheimer’s had progressed to the point where he no longer qualified for most studies.

A novel drug for inflammation

In late 2024, Karen brought Joe to Dr. Seth Gale, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham and Harvard Medical School who promised to look for a research study Walsh could enter.

Before long, Gale received a query from a colleague looking for a patient with moderate Alzheimer’s disease to take part in a trial. He called the Walshes.

The research involved a monoclonal antibody called foralumab that was being tested on people with inflammatory diseases including multiple sclerosis.

MS occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the protective covering around nerve fibers, causing inflammation. And foralumab was producing promising results in MS patients.

“It induces regulatory cells that go to the brain and shut down inflammation,” Weiner says.

Those regulatory cells reduce the activity of microglia, the cells that serve as the primary immune system in the brain and spinal cord.

Weiner thought foralumab might help with another condition that causes damaging inflammation in the nervous system.

“I’ve always been interested in Alzheimer’s disease,” Weiner says. “I lost my mother to Alzheimer’s disease.”

Most efforts to treat Alzheimer’s involve clearing the brain of the disease’s hallmarks: sticky amyloid plaques and tangled fibers called tau. But increasingly, researchers are seeking ways to tamp down the inflammation that accompanies those brain changes, especially as the disease progresses.

“Once people have Alzheimer’s, the inflammation is driving the disease more,” Weiner says.

The approach worked in mice that develop a form of Alzheimer’s.

But in order to treat Walsh, Weiner’s team had to get special permission from the Food and Drug Administration through a program called expanded access. The program is for patients who can’t get into a clinical trial and have no other treatment options.

When the FDA approved foralumab for Walsh, he became the first Alzheimer’s patient to get the treatment.

Six months later, the drug has dramatically reduced the inflammation in Walsh’s brain. But no drug can restore brain cells that have already been lost.

It will take a battery of cognitive tests to see if Walsh’s memory and thinking have improved with the treatment. Karen Walsh, though, sees some positive signs.

Although her husband still struggles to find words, she says, he appears to be more engaged in social activities.

“A couple of guys come pick him up once a month, you know, and they take him out for lunch,” she says. “They sent me a text after saying, ‘Wow, Joe is really, really laughing, and very involved.'”

Walsh himself seems happy to stay on the drug. Between non sequiturs, he manages to put together a complete sentence: “It’s easy enough to take it, so I do it, and it feels good.”

A clinical trial of foralumab for Alzheimer’s disease is scheduled to begin later this year.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

Researchers in Boston are trying an unusual new treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: All right. Ready?

JOE WALSH: Yeah.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: I’m going to start here.

J WALSH: Yeah.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: One, two, three.

(SOUNDBITE OF INHALING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Great job.

SHAPIRO: It’s a nasal spray designed to reduce inflammation in the brain. NPR’s Jon Hamilton reports on the first patient with Alzheimer’s to receive it.

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: His name is Joe Walsh, and he’s just inhaled a monoclonal antibody that will change the behavior of immune cells in his brain. Walsh and his wife, Karen, are in an exam room at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. A neurologist, Dr. Brahyan Mendez, has arrived to assess Walsh’s thinking and memory.

BRAHYAN MENDEZ: Can you tell me your name, please? What’s your name?

J WALSH: Joe.

MENDEZ: OK. And who is with you today?

J WALSH: We’ll do that.

MENDEZ: What’s her name?

J WALSH: Her name. That’s her name.

KAREN WALSH: (Laughter).

J WALSH: That’s my wife.

HAMILTON: Karen Walsh – the woman he’s been married to for 36 years. Back in 2017, she noticed a change in her husband.

K WALSH: He was struggling to find the right words to complete, like, a thought or a sentence.

HAMILTON: They saw a primary care doctor who said that if Walsh turned out to have Alzheimer’s, he should enter a research study in hopes of getting one of the latest treatments. Walsh was referred to a neurologist, and in 2019, a PET scan confirmed his diagnosis.

K WALSH: As much as I was in shock, the words were ringing in my head – you know, ask for the research.

HAMILTON: So she began looking for a clinical trial.

K WALSH: We started with blood work and signed all the paperwork, and then COVID hit in March of 2020.

HAMILTON: Hundreds of clinical trials were suspended, and by the time the pandemic subsided, Walsh’s Alzheimer’s had progressed to the point where he no longer qualified for most studies. Then, in 2024, Karen brought Joe to Dr. Seth Gale, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham.

SETH GALE: And I told them that I would keep my eye out for opportunity for some novel drug to take.

HAMILTON: Before long, Gale received a query from a colleague.

GALE: Does anyone know of a patient who has moderate Alzheimer’s disease? And I remembered Karen and Joe.

K WALSH: Dr. Gale called me, and he said, I think I have some research that Joe could be involved in. Would you be interested?

HAMILTON: The research involved a monoclonal antibody being tested on people with multiple sclerosis. MS occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the protective covering around nerve fibers, causing inflammation. Dr. Howard Weiner, a professor at Harvard and neurologist at Mass General Brigham, says the treatment was producing good results with MS patients.

HOWARD WEINER: It induces regulatory cells that go to the brain and shut down inflammation.

HAMILTON: So Weiner thought the monoclonal antibody, called foralumab, might work on another condition that damages the nervous system.

WEINER: I’ve always been interested in Alzheimer’s disease. I lost my mother to Alzheimer’s disease.

HAMILTON: Most efforts to treat Alzheimer’s involve clearing the brain of the disease’s hallmarks – sticky amyloid plaques and tangled fibers called tau. But Weiner says Alzheimer’s also causes inflammation in the brain, especially as the disease progresses.

WEINER: Once people have Alzheimer’s, the inflammation is driving the disease more. So if you give the drug to treat inflammation, the disease won’t progress as much and the patients will do better.

HAMILTON: At least that’s what Weiner is hoping. The approach worked in mice, but in order to treat Walsh, the researchers had to get special permission from the Food and Drug Administration. Once Walsh started taking foralumab, Weiner says, the inflammation in his brain began to subside.

WEINER: I’ve never seen anything like this, and we’ve tried a lot of things. So I think this is something special.

HAMILTON: Especially because the treatment appears to have no serious side effects. The results with Walsh are described in the journal Clinical Nuclear Medicine. Of course, the drug can’t restore lost brain cells, and it will take a battery of cognitive tests to see if it has helped Walsh’s memory and thinking. Karen Walsh says after six months of treatment, her husband still struggles to find words, but she thinks he’s become more engaged in social activities.

K WALSH: A couple of guys come pick him up once a month, you know, and they take him out for lunch. They sent me a text after, saying, wow, Joe is really smiling, really laughing and very involved. So that’s where I’m seeing more of the change.

HAMILTON: As for Joe Walsh, he says he’s OK with staying on the drug.

J WALSH: It’s easy enough to take it, and so I do it, and it feels good.

HAMILTON: A clinical trial of foralumab for Alzheimer’s disease is scheduled to begin later this year.

Jon Hamilton, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

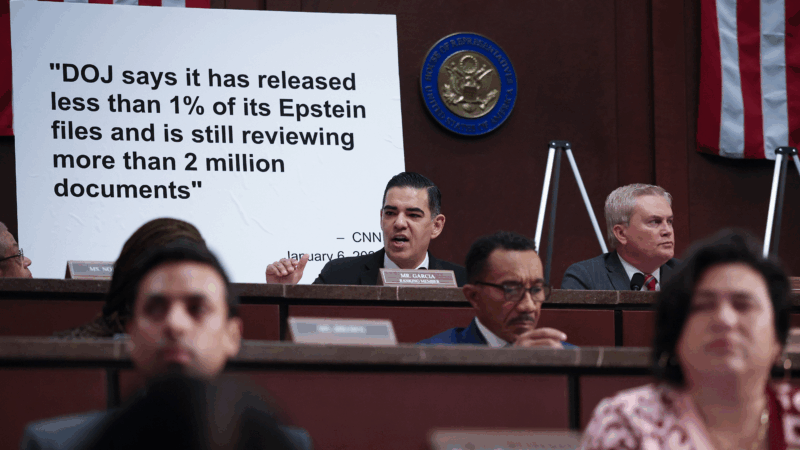

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

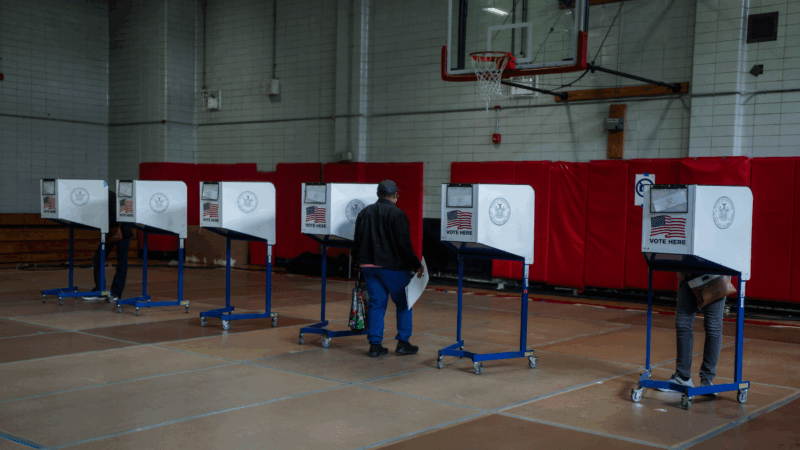

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026 shortlist includes Lauryn Hill, Shakira and Wu-Tang Clan

The shortlist also includes a 1990s pop diva, heavy metal pioneers and a legendary R&B singer and producer.