‘Broadcasting’ has its roots in agriculture. Here’s how it made its way into media

Broadcasters keep popping up in the news.

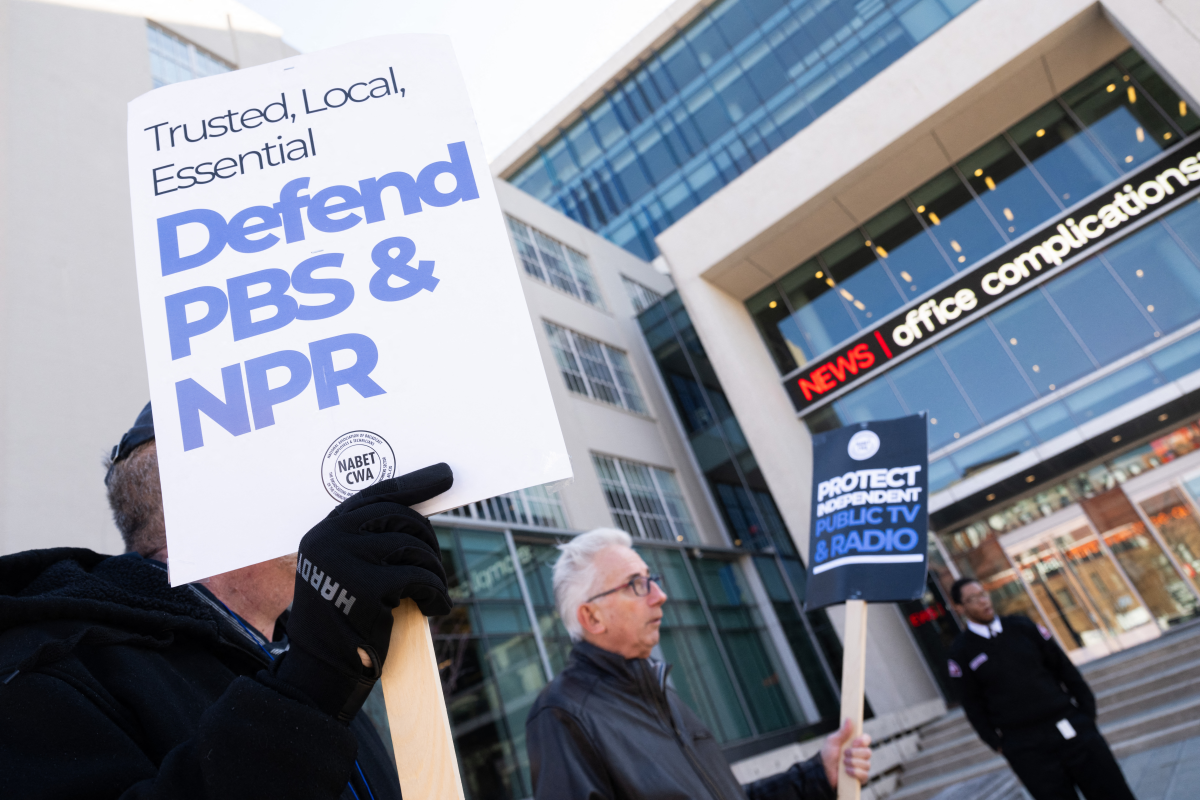

Commercial TV networks have made headlines: CBS announced the cancellation of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert this summer. ABC drew ire in September when it yanked Jimmy Kimmel off the air, albeit briefly, under pressure from the Trump administration due to comments Kimmel had made after Charlie Kirk’s death. President Trump has also set his sights on public broadcasters, accusing them of liberal bias and successfully pressuring Congress to rescind $1.1 billion in previously allocated funding for NPR and PBS.

Broadcasting — distributing radio and television content for public audiences — has been around for a century, but is facing a uniquely challenging landscape today.

So it’s only fitting that NPR’s Word of the Week series is tackling the origins of the word “broadcasting” – whose roots aren’t in radio or television, but in agriculture. It originally described a method of planting seeds, particularly for small grains like wheat, oats and barley.

“And it comes from the way that you would plant it: on a prepared field, where you would scatter it broadly across the ground,” says Leo Landis, the director of public history at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Various dictionaries have traced the verb’s first written use — to sow seed over a broad area — to 1733 and 1744.

The phrase blossomed across Great Britain and the colonial U.S., and by the early 1800s was a fixture in agricultural guides, Landis says. And it remains one of the dominant planting techniques to this day.

“The thing that many people don’t know today is that if they’re working on their lawn and using either a commercial planter or just scattering seed by hand, they are broadcast seeding,” Landis says. “So it’s a term that may have lost that connection for some people, but it’s still a practice that many people use today.”

These days, though, broadcasting is more widely associated with the dissemination of news and entertainment than seeds of grain.

“It describes something that the government has technical and engineering standards for, but it also describes something that we all talk about and we all live with, which is our radios and our televisions,” says Michael Socolow, a professor of communication and journalism at the University of Maine.

So how did that come to be?

Broadcasting’s radio rebrand

The use of the term “broadcasting” to describe radio first hit the mainstream in the early 1920s. Radio signals (formerly called “wireless telegraphy”) and amateur broadcasts existed before that, Socolow says.

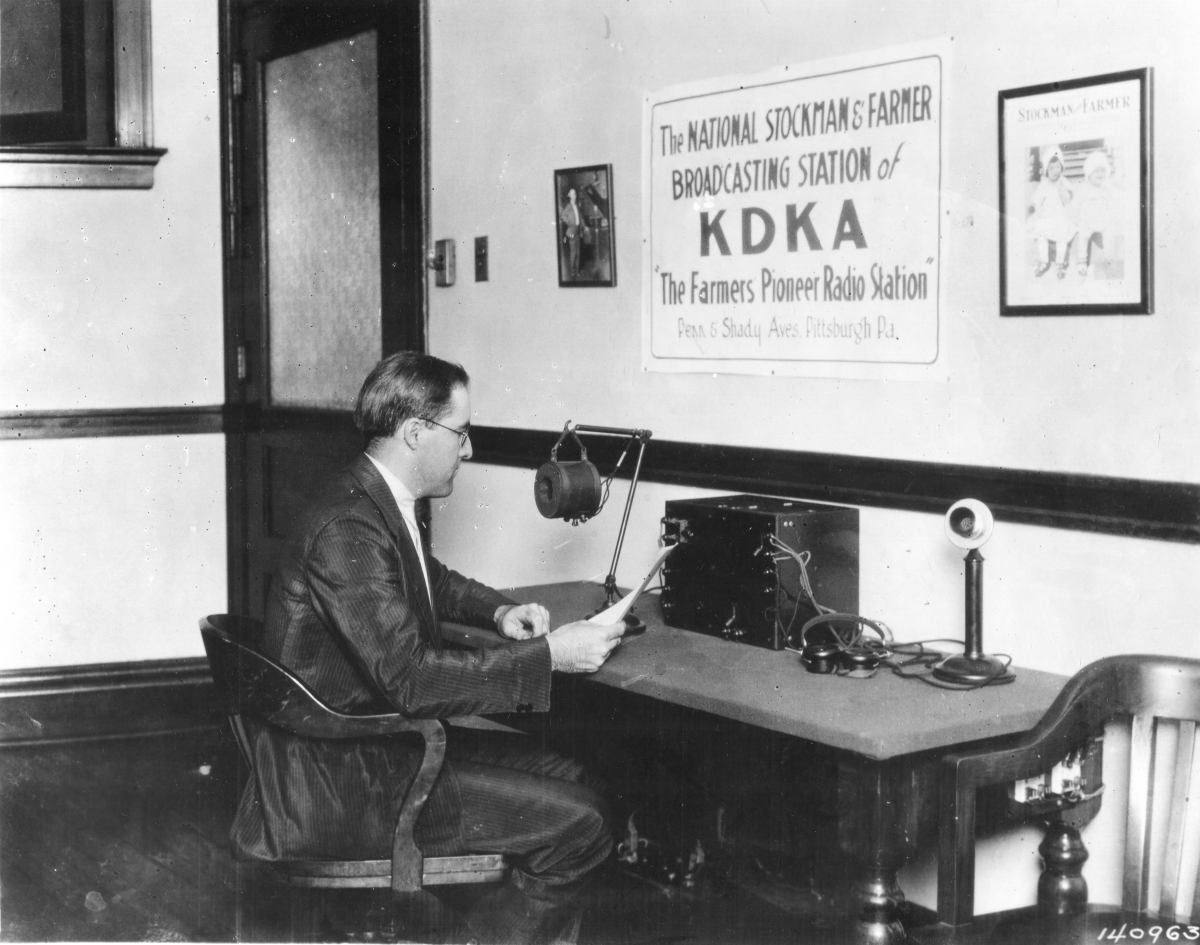

But change ignited on the night of Nov. 2, 1920, when a Westinghouse plant engineer named Frank Conrad broadcast the presidential election results from Pittsburgh’s KDKA, the first commercially licensed station in the country.

“He got very lucky because it was a landslide election, so he was able to broadcast in the early evening that [Warren] Harding had won,” Socolow says. “And this kind of electrified the country. It got tons of newspaper coverage the next day as sort of a peek into the future.”

In fact, he says, many more people read about Conrad’s broadcast than heard it themselves, since radios weren’t yet commonplace in American homes.

But that changed throughout the 1920s, as more Americans started living in urban areas, rather than rural ones, for the first time. The price of radios dropped dramatically towards the end of the decade, around the time of the creation of the nation’s first major networks, NBC and CBS.

By 1930, 40 percent of American households owned a radio, a number that more than doubled over the next decade.

It was a piece of legislation that officially cemented broadcasting’s new definition: The Communications Act of 1934 defined it as “the dissemination of radio communications intended to be received by the public, directly or by the intermediary of relay stations.” Its new meaning entered the public lexicon, too.

“By the end of the 1930s, when you used the word ‘broadcasting,’ Americans all knew it meant radio broadcasting,” Socolow says.

They tuned in to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Fireside Chats,” a series of evening radio addresses between 1933 and 1944, as well as sports — especially boxing, horse racing and baseball — comedy shows and radio mysteries. Some even alleged addiction, like the Minneapolis woman who sued to divorce her husband over his “radio mania” in 1923.

From there, World War II ushered in the rise of network radio news — think CBS’ Edward R. Murrow’s live wartime broadcasts from London — and a shift toward listening in public spaces, like hotels and buses.

“Americans really grew pretty intensely … reliant on radio and radio news in World War II,” Socolow says.

Broadcasting becomes a shorthand

After WWII, the major commercial networks started pouring their profits into funding television programming as technology developed.

TV officially surpassed radio as the most popular broadcast medium in the 1950s. In response, Socolow says, radio networks began to focus more on talk shows, live news and localized programming.

“Radio is moving into cars, and as suburbia grows, radio broadcasting to automobiles becomes a massive business,” he says. “This is where radio broadcasting in the late 1950s and early 1960s really takes off and stays a vital news source and a profitable medium, by changing what it does.”

And it wasn’t all commercial: The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 established the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, leading to the creation of NPR and PBS.

These days, people tend to use the word to describe any sort of dissemination of information — even if it comes from cable news networks, social media platforms and streaming services, which are not technically broadcasters under the government’s definition, Socolow says.

“CNN does not broadcast, Fox News does not broadcast, TikTok does not broadcast,” he says. “It’s very interesting that the concept of broadcasting, which has become sending video to masses and millions of people, has remained, even though the technologies have changed and it isn’t broadcasting as it was understood for most of the 20th century.”

Why it matters today

Even in the digital age, broadcast television and radio remain a key source of information, entertainment, connection and emergency warnings.

Landis says TV and radio help shape culture and spread the word, much as newspapers and telegraphy did in the 1800s.

“Having a shared understanding of experiences and even information is just so critical to living in a democratic republic,” he adds.

Socolow agrees, adding that modern broadcasting has not only documented but influenced many of the key historical events from the past century — from wars to political campaigns to social movements.

“What people actually know and learn are shaped, their universe and their reality are shaped, by their knowledge that’s gained through broadcasting,” he adds. “So it’s incredibly important to understand the past first in that way. “

And it’s not just a matter of the historical record.

A Pew Research Center survey released last month found that while digital devices are the most common way Americans consume news, a majority (64%) get their news from television “at least sometimes” and 32% do so often — a number that Pew says has stayed fairly steady over the last few years.

Despite ongoing change, Socolow predicts that TV and radio broadcasting will evolve to “work their way around the habits of younger Americans in different ways.” It wouldn’t be the first time.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

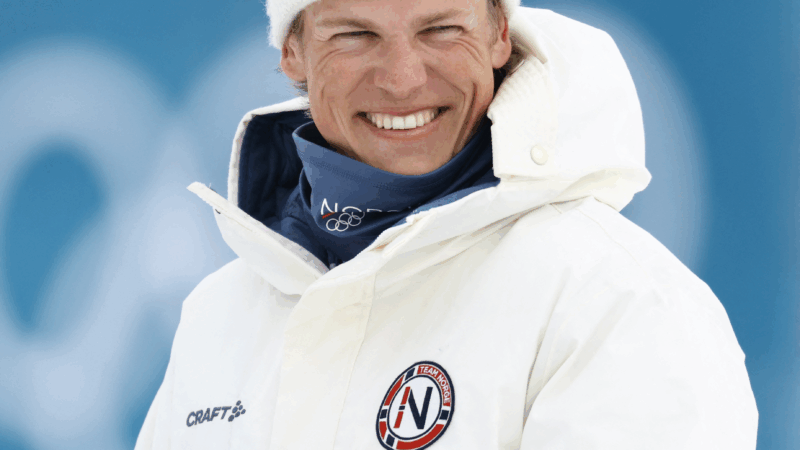

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.

Willie Colón, salsa pioneer, has died at 75

The South Bronx bandleader took the Latin genre to new heights while recording for Fania Records.