Bad Bunny skipped touring the states. Will other performers follow suit?

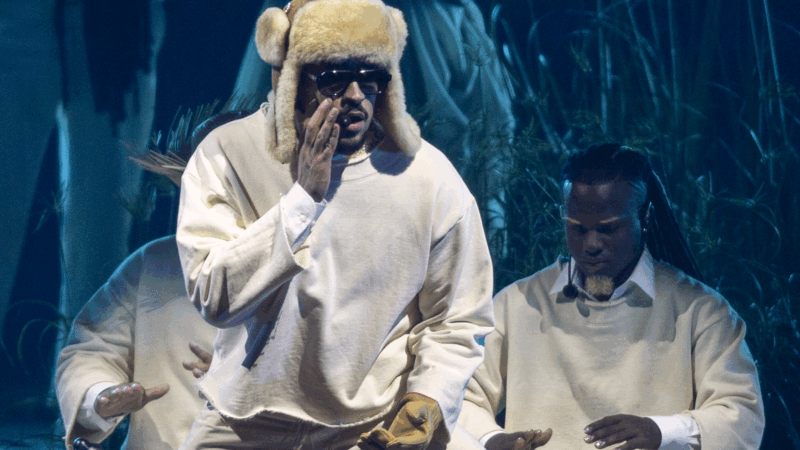

In an interview with I-D magazine earlier this month, megastar Puerto Rican singer and rapper Bad Bunny said he chose not to do any concert dates in the 50 states during his current world tour, because he’s afraid that ICE, as he said, “could be outside my concert.” Instead, he did 30 shows in Puerto Rico, which reportedly brought hundreds of millions of tourism dollars to the island.

As a Puerto Rican, Bad Bunny is, of course, a U.S. citizen. Performers from other nations are facing additional issues — notably hurdles in securing visas.

Performers, event presenters, booking agents and lawyers tell NPR that they are dealing with a lot of uncertainty right now – and they have been very hesitant to speak on the record. They fear retaliation, including by those who hold decision-making power over visa approvals or from those who hold financial sway, because they control state, local or private funding.

Bad Bunny publicly expressed concerns that his Latino fans would be targeted for ICE enforcement. What does the Department of Homeland Security say?

In a written statement to NPR Thursday, assistant DHS secretary Tricia McLaughlin wrote:

“Bad Bunny is either seriously misinformed about ICE operations or is using law enforcement as an excuse because he won’t be able to sell tickets in the United States. ICE is not raiding concert venues. Pop stars choosing to fearmonger and demonize ICE law enforcement are contributing to the nearly 1,000% increase in assaults on ICE officers. If Sabrina Carpenter and Tate McRae are going on tour, so can he.”

The Department of Homeland Security has not provided further details or evidence about those assault claims; in July, DHS Secretary Kristi Noem defined violence against ICE officers as including doxxing agents and videotaping officers.

Are other performers expressing similar concerns?

People in the entertainment and the arts industries say they continue to be concerned. In July, community leaders and local officials in Chicago accused federal agents of targeting attendees at the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts & Culture, and shared video of ICE agents at their museum. The Department of Homeland Security denied those accusations at the time. Regardless, folks working in culture and entertainment are worried about similar situations potentially happening at their events.

What about foreign artists who want to come to the United States?

Foreign visitors coming to the U.S. as entertainers need to have a specific kind of work visa, and some artists and presenters have had dates canceled or delayed due to visa issues. Earlier this month, the Korean boy band Be:Max was forced to cancel U.S. tour dates, saying that their visas had been canceled close to their planned appearances. (NPR reached out repeatedly to Be:Max and their concert promoters, but did not receive any replies.) In July, the duo TwoSet Violin postponed a number of U.S. dates when its member Brett Yang, an Australian violinist, had his initial visa application rejected.

But there are now new financial and logistical hurdles to overcome in the process of getting a visa. Earlier this month, the State Department announced that applicants have to return to their country of nationality or full-time residency to apply for visas to visit the U.S. And that creates big, expensive complications for performers who earn their money touring the world.

What does this mean for artists?

Here’s a hypothetical example: Say a performer originally from India wants to apply to come do a tour in the U.S. — but they are temporarily working in Belgium. It used to be that they could go to the U.S. consulate in Belgium for their U.S. visa interview. The State Department is now saying no, they have to fly home to India to apply and be interviewed there. That costs a lot of money and time, especially for touring groups with big bands and crews. As it is, visa applications can cost upwards of $8,000 per person, including legal fees.

NPR reached out to the State Department for comment, which said that they are “upholding the highest standards of national security and public safety through our visa process.”

So how long does the visa process take?

As of right now, the government’s website estimates that for the types of visas visiting performers typically use (O and P category visas), it will take seven months. Immigration lawyers tell NPR that seven months is an optimistic estimate — and are advising their clients to expect the process to take even longer. So if an artist wants to come perform in the U.S. in Sept. 2026, they had best get moving. And that is going to affect which touring artists may ultimately decide to make a decision like Bad Bunny and say, “Given the current circumstances, never mind. We’ll just skip the United States for now.”

Jennifer Vanasco edited this story for broadcast and digital.

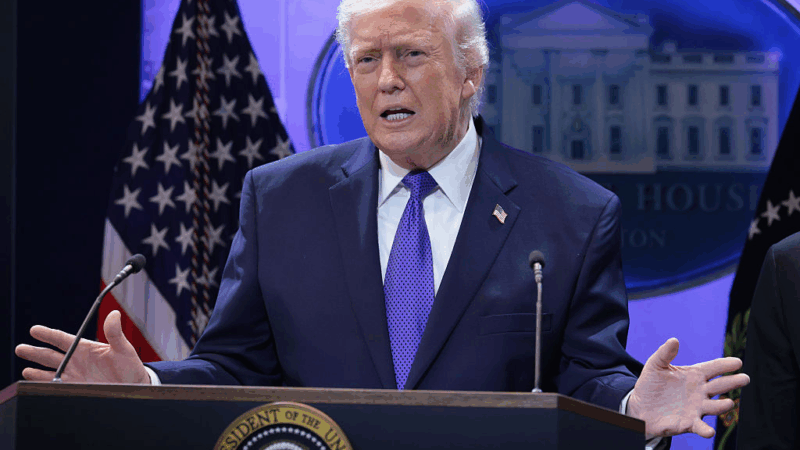

Trump to raise global tariffs. And, most say the state of the union is weak, poll says

President Trump says he is raising global tariffs to 15%. And ahead of the president's address tomorrow, most Americans say the state of the union is not strong, according to an NPR poll.

U.S. has a quarter fewer immigration judges than it did a year ago. Here’s why

The continued drain of personnel from the already strained immigration court system has contributed to depleted staff morale, mounting case backlogs — and floundering due process.

Poll: Most say the state of the union is not strong and the U.S. is worse off

Ahead of the State of the Union address on Tuesday, evidence continues to mount that President Trump is facing political headwinds.

Influencers are promoting peptides for better health. What’s the science say?

The latest wellness craze involves injecting these molecules for athletic performance, longevity and more. Scientists say the research isn't keeping pace with the health claims.

The owners want to close this Colorado coal plant. The Trump administration says no

The Trump administration has ordered several coal plants to keep operating past their planned retirement, part of a larger effort to boost the coal industry. Two Colorado utilities are pushing back.

Mexico fears more violence after army kills leader of powerful Jalisco cartel

School was canceled in several Mexican states and local and foreign governments alike warned their citizens to stay inside following the army's killing of the leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Nemesio Rubén Oseguera Cervantes, "El Mencho," and the violence it spurred