As Trump dismantles the existing world order, his version is still taking shape

President Harry Truman led the construction of the global order from the smoldering ruins of World War II. The U.S. played a starring role in these international organizations such as the United Nations, the World Bank and NATO.

“In this treaty, we seek to establish freedom from aggression and from the use of force in the North Atlantic community,” Truman said at NATO’s founding in 1949 in Washington, D.C.

That NATO community, then and now, includes Greenland, a semiautonomous territory that for three centuries has been part of Denmark, a NATO member.

Yet President Trump has a different take.

“We are going to do something on Greenland, whether they like it or not. Because if we don’t do it, Russia or China will take over Greenland,” Trump said recently.

Many foreign policy analysts are critical of Trump’s call for U.S. control of Greenland. Yet the president has doubled down, in keeping with his aggressive, unilateral approach to foreign policy.

Trump breaks from a long tradition

For 80 years, almost all U.S. presidents — Democratic and Republican — have worked largely from the same playbook. With the U.S. as the anchor, this international order was based on a global network of military alliances, an emphasis on free trade and calls for greater democracy.

The U.S. and its allies have hugely benefited from this system. But the world has changed. Some of these institutions have not kept pace, and Trump often describes them as burdens that constrict his desire for swift, decisive action.

“You can make an argument that Trump’s version of shock therapy was necessary to get U.S. allies out of the world of complacency that they had been living in for far too long,” said Hal Brands, a senior fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute in Washington. “The challenge, though, is that if you don’t pair that with reassurance, you risk hollowing out the credibility of these alliances instead of improving them.”

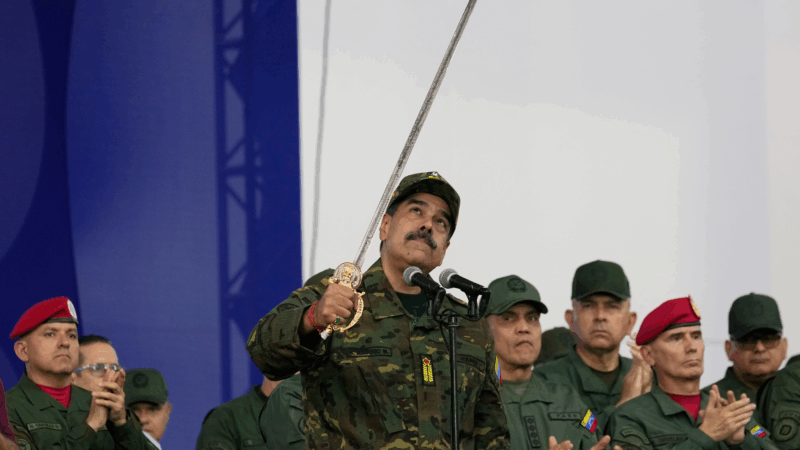

In his first term, Trump sought to keep the U.S. out of foreign conflicts. In his second term, Trump has often turned to military force. In the past year, the U.S. has bombed four countries in the Middle East (Iran, Iraq, Syria and Yemen) and two in Africa (Nigeria and Somalia). Trump has threatened others, both friends and foes. And the U.S. recently ousted Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro.

“The American people need to be asking the question, are these military interventions enhancing our security and our prosperity and our values? In my estimation, they are not,” said Michael McFaul, a former U.S. ambassador to Russia.

In Venezuela, Trump is working with the holdovers of Maduro’s regime. He’s lukewarm at best toward the country’s opposition, which was widely considered the winner of the 2024 presidential election.

McFaul has written a new book entitled Autocrats vs. Democrats. He says that in several places, including Venezuela, “I’m not sure what side of that divide President Trump is on. He could have easily just said, ‘We’re removing Maduro and we are now going to help the democratically elected president.'”

An emphasis on the Western Hemisphere

As Trump takes apart the 20th-century world order, he’s embracing elements of 19th-century U.S. foreign policy — like the Monroe Doctrine, which dates to President James Monroe’s 1823 declaration that European colonial powers should not meddle in the Western Hemisphere. Trump is now touting his own version — the Donroe Doctrine.

The State Department summed it up in a social media post that showed a scowling Trump with the words: “This is our hemisphere.”

While Trump is much more aggressive in calling on the U.S. military in this term, compared to his first term, he’s targeted smaller countries.

“Trump is very good at beating up on weaker states where the power asymmetry with the United States is most severe,” said Brands. “Trump has been extremely effective at coercing Iran. He’s been effective at coercing Venezuela.”

Trump says these shows of strength give the U.S. leverage when it comes to making peace. The president has had diplomatic breakthroughs, including a ceasefire agreement in the Israel-Hamas conflict.

But Brands notes that Trump has been stymied when dealing with the U.S.’ most powerful rivals, Russia and China.

“He has been far less effective at coercing Russia to end the war in Ukraine and far less effective at coercing China on economic or strategic matters,” said Brands.

The Russia-Ukraine war grinds on, despite Trump’s efforts to broker a peace deal. With China, Washington and Beijing have effectively called a truce in their trade war, at least for now.

U.S. allies question Washington’s reliability

Trump’s combative approach also extends to many U.S. allies, and is changing their calculus when it comes to depending on the U.S., said Ian Bremmer, who heads the Eurasia Group, a global research and consulting firm based in New York.

“Our allies are playing defense in the near-term because they don’t want to get hurt. They don’t want to be in a fight with the U.S,” said Bremmer. “Long-term, they’re hedging. They’re doing everything they can to not have to rely on the United States as much.”

Bremmer said Trump consistently overestimates unilateral U.S. clout, and underestimates the value of partners.

“The Americans are giving away the store long-term on what has allowed them to so successfully project power,” he said. “It has been a willingness to align, not all the time, but a fair amount, with allies. Trump is throwing that out the window.”

As this old order breaks down, Trump’s version is still taking shape.

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

In a series of stories, NPR is exploring America’s changing role in the world. Today, we look at how President Trump is upending the global order. This comes as Trump takes an increasingly strident tone about possible action in Iran. Here’s NPR’s Greg Myre on the way Trump is redefining America first.

GREG MYRE, BYLINE: The year is 1949. President Harry Truman is building a new global order from the smoldering ruins of World War II. The U.S. takes the starring role in international organizations like NATO.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

HARRY TRUMAN: In this treaty, we seek to establish freedom from aggression and from the use of force in the North Atlantic community.

MYRE: The NATO community, then and now, includes Greenland. And here’s what President Trump is now saying.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: We are going to do something on Greenland whether they like it or not, because if we don’t do it, Russia or China will take over Greenland.

MYRE: In his first term, Trump scaled back the U.S. role in a host of international institutions. He still sees these networks as a burden. What’s new this time around is his willingness to turn to the military. In the past year, the U.S. has bombed four countries in the Middle East and two in Africa. Trump has threatened others, both friends and foes, and the U.S. recently ousted Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

TRUMP: We’re going to run it, essentially, until such time as a proper transition can take place.

MYRE: Michael McFaul is a former U.S. ambassador to Russia.

MICHAEL MCFAUL: The American people need to be asking the question, are these military interventions enhancing our security and our prosperity and our values? And in my estimation, they are not.

MYRE: In Venezuela, Trump is working with the holdovers of Maduro’s regime. He’s dismissive of the country’s opposition, though its candidate was considered the overwhelming winner in a 2024 presidential election. McFaul has a new book entitled “Autocrats Vs. Democrats.” He says that in several places, including Venezuela…

MCFAUL: I’m not sure what side of that divide President Trump is on. He could have easily just said, we’re removing Maduro and we are now going to help the democratically elected president.

MYRE: As Trump takes apart the 20th century world order, he’s embracing elements of 19th century foreign policy, like the Monroe Doctrine. This dates to President James Monroe’s 1823 declaration that European colonial powers should not meddle in the Western Hemisphere. Since then, U.S. presidents have given this their own interpretation. Trump is now touting his version, the Donroe Doctrine. The State Department summed it up in a social media post that showed a scowling Trump with the words, this is our hemisphere. Ian Bremmer heads the Eurasia Group, a global research and consulting firm. He says Trump is having an impact on Latin America and beyond.

IAN BREMMER: Allies are playing defense in the near term because they don’t want to get hurt. They don’t want to be in a fight with the U.S. But long term, they’re hedging. Long term, they’re doing everything they can to not have to rely on the United States as much.

MYRE: Foreign policy analysts say Trump is also expressing a related 19th century notion – spheres of influence. The idea is that large powers can impose their will in their own regions and smaller countries have little choice but to comply. In short, the U.S. will dominate the Western Hemisphere, Russia’s Vladimir Putin will play a leading role in Europe and China’s Xi Jinping will dictate terms in Asia. Hal Brands is with the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

HAL BRANDS: If great powers just sort of get to do what they want in their respective spheres of influence, that’s kind of the world that Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin want to bring about. It’s a world that they would be very comfortable with.

MYRE: In his first term, Trump wanted to pull U.S. troops out of foreign conflicts. This time, he sent the military on bombing raids against countries that include Iran and Yemen in the Middle East, and Nigeria and Somalia in Africa. Brands sees a pattern.

BRANDS: The preferred Trump method of military intervention is you use a lot of force to hit somebody really hard. And then you let somebody else sort out the consequences.

MYRE: Trump says these shows of strength give the U.S. leverage when it comes to making peace. And the president has had diplomatic successes, like a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas conflict. Still, Ian Bremmer says Trump overestimates unilateral U.S. clout and underestimates the value of partners.

BREMMER: The Americans are giving away the store long term on what has allowed them to so successfully project power. It has been a willingness to align, not all the time but a fair amount, with allies. And Trump is throwing that out the window.

MYRE: Meanwhile, the president’s global pullback continues. Last week, the Trump administration announced the U.S. withdrawal from 66 international organizations. His administration called them wasteful and ineffective.

Greg Myre, NPR News, Washington.

The divorce between the U.S. and WHO is final this week. Or is it?

The U.S. is the only country allowed to withdraw from the World Health Organization. And Jan. 22 is the day when Trump's pullout announcement should go into effect. But ... it's complicated.

Trump’s Board of Peace has several invited leaders trying to figure out how it’ll work

It's unclear how many leaders have been asked to join the board, and the large number of invitations being sent out, including to countries that don't get along, has raised questions about the board's mandate and decision-making processes.

Researchers find Antarctic penguin breeding is heating up sooner

Warming temperatures are forcing Antarctic penguins to breed earlier and that's a big problem for two of the cute tuxedoed species that face extinction by the end of the century, a study said.

Medicaid has a new way to pay for costly sickle cell treatment: Only if it works

Medicaid is doing a novel payment system for the new, promising and expensive sickle cell treatment. It may become a model for all gene therapies being developed.

Polyester clothing has been causing a stir online. But how valid are the concerns?

There has been a lot of conversation on social media about the downsides of polyester. But are those downsides as bad as they're believed to be? Are there upsides?

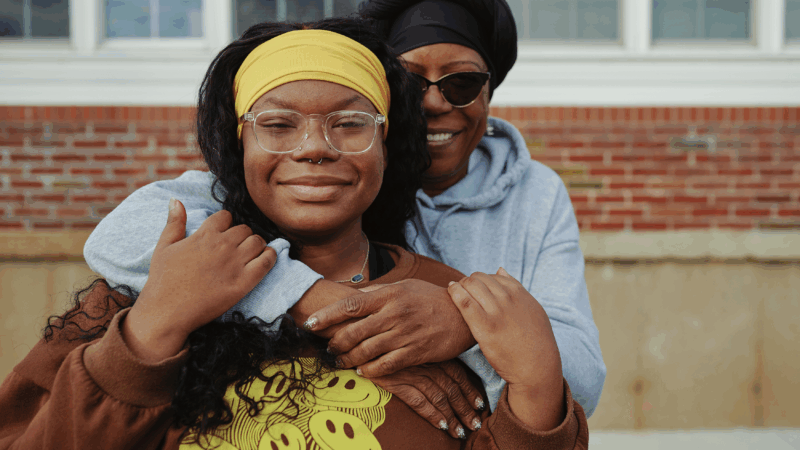

New Orleans brings back the house call, sending nurses to visit newborns and moms

Louisiana has long struggled with maternal and infant mortality. In New Orleans, free home visits by nurses help spot medical problems early. It's a reproductive health policy with bipartisan support.