As sports betting explodes, should states set more limits to stop gambling addiction?

It’s hard to promote moderation and financial discipline from the bowels of a casino.

But that’s what Massachusetts state workers try to do every day, amid the clanging bells and flashing lights of the slot machines.

At the MGM Springfield in western Massachusetts, these workers, wearing green polos, stand outside their small office, right off the casino floor.

Above them the sign reads, “GameSense,” the state’s signature program to curb problem gambling.

A mounted screen cycles through messages such as “Keep sports betting fun. Set a budget and stick to it.”

The workers hand out free luggage tags and travel-size tissues in an effort to get people to stop and chat.

If they succeed, they give customers brochures with the state’s gambling helpline number and website. They can even enroll them in a program, called Play My Way, that allows customers to set monthly spending limits on how much they gamble.

Outside the casinos, GameSense is marketed on social media and on sportsbook apps and websites. Meanwhile, the state’s Department of Public Health puts its own moderation messages on buses and billboards.

“That’s a big movement in 12 years,” says Mark Vander Linden, who oversees the GameSense program for Massachusetts.

Massachusetts’ first casino opened in 2015, and as the gaming industry grew, the state developed what it calls a “responsible gaming” program, funded by a surtax on gambling industry profits.

(Karen Brown | NEPM)

At first, the state regulators tried various strategies to educate customers about the addictive nature of gambling, as well as the financial risks.

“It was much more about making sure that there are brochures that are available that explained the odds of whatever game it was,” he says.

Since then, Massachusetts has put in place additional regulations on a booming industry that now includes widespread sports betting. For example, there’s no betting on Massachusetts college teams, and no gambling by credit card. All gambling companies have to allow customers to set voluntary limits and sign up for a “voluntary self-exclusion list” that bans them from casinos or sports betting over various time intervals.

U.S. has no national gambling policy, unlike other countries

Some states have set similar limits in an effort to curb problem gambling, but others have very few. In the absence of a nationwide policy, or a national gambling commission to oversee the industry, each state is on its own.

Now a growing number of addiction researchers and policy makers say it’s time to take bolder — and more unified — steps to combat gambling disorders. They point to the explosion of the gaming industry since 2018, when the U.S. Supreme Court opened the door for states to legalize sports betting and unleashed an aggressive new industry, now legal in 39 states. (Forty-eight states have legalized at least some form of gambling, including lotteries.)

Compared to the U.S., several other countries have gone much further in regulating the gambling industry, and some experts in the U.S. are looking to them as potential models.

For example, Norway’s government has a monopoly on all slot machines so it can control the types of games offered, and every gambler in the country is limited to losing only 20,000 kroner (about $2,000) a month.

In the United Kingdom, there’s a new 5 pound limit (about $7) on every spin on a slot machine, and gambling companies are now subject to a 1 percent levy that goes into a fund for treatment and prevention of gambling disorders.

(Karen Brown | NEPM)

Earlier this year, a report published in the medical journal The Lancet called on international health leaders to act quickly on regulations before gambling disorders become widespread and common, and that much harder to stop.

But policy leaders point out that the U.S. has less appetite for corporate regulation than many other countries, especially in the Trump administration. At the same time, they warn that doing nothing could pose a serious public health threat, especially now that sports betting apps allow people to gamble anywhere and anytime.

Fears that more gambling means more addiction

Even before the marriage of online gaming and cellphones, researchers had estimated 1% to 2% of Americans already had a gambling disorder, and another 8%of people were at risk of developing one.

Some U.S. politicians fear the problem will only get worse.

“The sophistication and complexity of betting has become staggering,” says Democratic U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut. “And that’s why we need protections that will enable an individual to say no.”

Blumenthal has co-sponsored the SAFE Bet Act, legislation that would impose federal standards on sports betting companies.

The bill proposes a ban on gambling ads during live sporting events, mandatory “affordability checks” for high-spending customers, limits on “VIP” membership schemes, a ban on AI tracking for marketing, and the creation of a national “self-exclusion” database, among other rules.

“States are unable to protect their consumers from the excessive and abusive offers, and sometimes misleading pitches,” Blumenthal says. “They simply don’t have the resources or the jurisdiction.”

The gambling industry is strongly opposed to lobbying against the SAFE Bet Act. Federal standards would be a “slap in the face” to state regulators, says Joe Maloney, a spokesperson for the American Gaming Association.

“You have the potential to just dramatically, one, usurp the states’ authority and then, two, freeze the industry in place,” he says.

‘Responsible gaming’ is different from a public health approach

New regulations are also unnecessary, Maloney says. The industry acknowledges that gambling is addictive for some people, he says, which is why it developed an outreach/awareness initiative known as “responsible gaming.”

That includes messages on buses and billboards warning people to stop playing when it’s no longer fun and reminding them the odds of winning are very low.

“There’s very direct messages, such as – ‘you will lose money here,'” Maloney says.

He says his industry group does not collect data on whether those measures reduce addiction rates. But he says gambling restrictions are not the answer.

“If you suddenly start to pick and choose what can be legal or banned, you’re driving bettors out of the legal market and into the illegal market,” Maloney says.

But public health leaders say the industry’s “responsible gaming” model just doesn’t work.

“You need regulation when the industry has shown an inability and unwillingness to police itself,” says Harry Levant, director of gambling policy for the Public Health Advocacy Institute at Northeastern University in Boston.

One reason the industry’s approach is “ethically and scientifically flawed” is that it puts all the blame and responsibility on individuals with a gambling disorder, Levant says.

“You can’t say to a person who is struggling with addiction, ‘well just don’t do that anymore,'” Levant says.

Levant comes to the issue from personal experience. He is in recovery from a gambling addiction himself. A former lawyer, Levant was convicted in 2015 for stealing clients’ money to fund his betting habit. Since then, he has not only become an advocate for stronger regulations, but is a trained addiction therapist.

The American Gaming Association says it supports treatment for gambling disorder, and helps pay for some referral and treatment services through state taxes. But Levant calls that “the moral equivalent of Big Tobacco saying, ‘Let us do whatever we want for our cigarettes, as long as we pay for chemotherapy and hospice.'”

Instead, Levant advocates for a public health approach that would help prevent addiction from the get-go. That means putting limits on marketing and on the types — and frequency — of gambling — for everyone, not just those already in trouble.

Can lawmakers stop ‘the worst excesses’ before the next gambling trend?

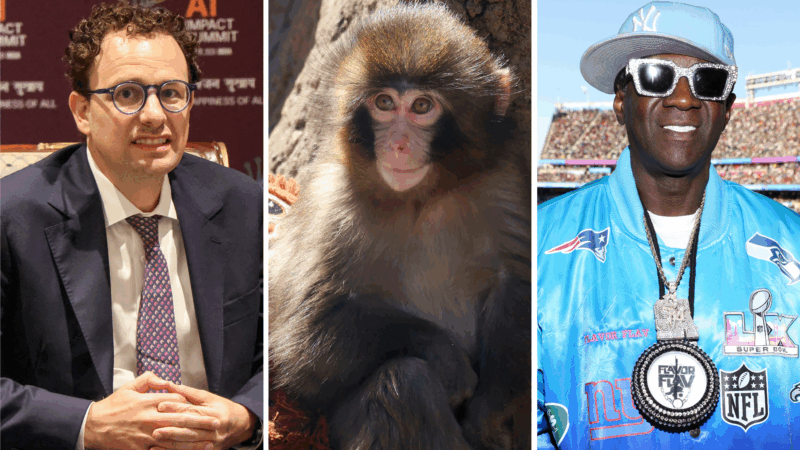

To make his case, Levant opens his laptop and pulls up a corporate infomercial produced by SimpleBet, a DraftKings subsidiary.

In the video, the company boasts about getting more people to gamble on sports through what’s called micro-betting during live games. “We drive fan engagement by making every moment of every game a betting opportunity. Automatic, algorithmic, powered by machine learning and AI,” the voiceover says.

That’s the kind of constant engagement that promotes addiction, Levant says. (Contacted by NPR, DraftKings declined to comment.)

Some of those gambling mechanisms would be limited by the SAFE Bet Act, which Levant and his colleagues at the Public Health Advocacy Institute helped write.

But if the legislation doesn’t get through the current regulation-averse Congress, then states need to take strong action on their own, Levant says.

The Massachusetts legislature is currently considering the Bettor Health Act, which would impose additional rules on sports betting companies.

“The goal is not to stop gambling entirely,” says Massachusetts state Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa, a cosponsor of the bill. “It’s to stop the worst excesses of online sports betting.”

The Massachusetts bill includes some components of the federal legislation, such as mandatory “affordability checks.” Those would cap how much money some gamblers can lose. Affordability checks are modeled on a pilot program in the United Kingdom.

“If you’re only allowed to have two drinks, we know that you’re not going to get drunk, right?” says Sabadosa. “If you’re only allowed to gamble $100 a day because that’s an affordable amount, you’re not going to go broke. You’re still going to be able to pay the rent.”

The Bettor Health Act would also ban “prop” bets, which are wagers placed during a live game, like who makes the first shot in basketball, or who hits the first home run in baseball.

But state tax revenue from sports betting rose to $2.2 billion in 2023 — a welcome source of funding for struggling state budgets. Because of that, Levant fears that state legislatures will shy away from further regulation.

States may even be tempted by the promise of additional revenues from new types of gambling, such as “i-gaming.” That refers to online versions of roulette, blackjack and other casino-style games, playable at any hour, from the comfort of your own home.

I-gaming is currently legal in only seven states, but pending legislation in other states, including Massachusetts, could expand its markets.

“We have empathy for how hard it is for states to balance their budgets in this current political environment,” Levant says, “but states are starting to recognize that the answer to that problem is not to further push a known addictive product.”

This story comes from NPR’s health reporting partnership with New England Public Media and KFF Health News.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country

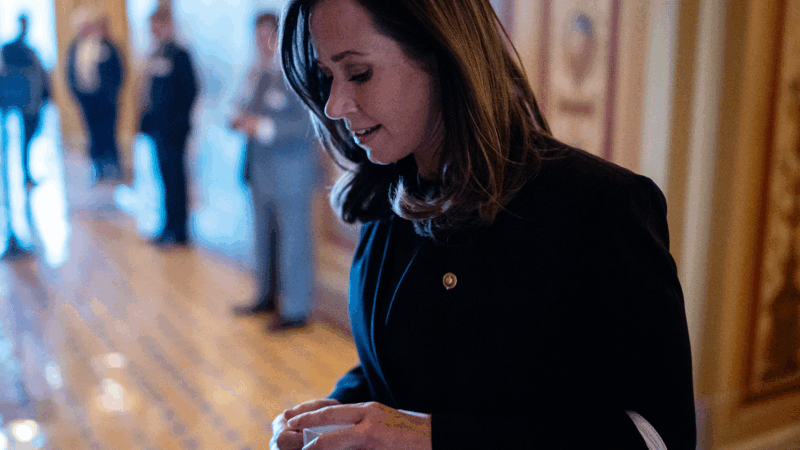

SNL mocked her as a ‘scary mom.’ In the Senate, Katie Britt is an emerging dealmaker

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

Nancy Guthrie case: How do families of missing people cope with the uncertainty?

When a loved one goes missing, relatives can feel guilty simply for eating, says Charlie Shunick, whose sister was kidnapped. Shunick now helps others navigate a nightmare "nobody is prepared for."

This community festival embraces the joys of a frozen lake — while it still has one

As climate change accelerates, local experts say the date Wisconsin's Lake Mendota freezes over is getting later, making safe conditions for activities that rely on snow and ice harder to predict.