Are you a glucose ‘dipper’? Here’s how to fix those blood sugar highs and lows

By all measurements, Judy Freeman, age 76, is in fantastic health. She doesn’t have diabetes or heart disease. She’s not overweight. She stays active.

“I try to walk at least four or five times a week,” says Freeman, who’s a well-known potter in Alpine, Texas. “I also work about 20 hours in the studio.”

But in the past year or so, Freeman hasn’t felt like herself. She’s been more tired and sluggish. And she has had more trouble shedding a little extra weight. “I try and I can’t lose it,” she says.

So Freeman decided to experiment with a new technology for a few weeks: a continuous glucose monitor.

It’s a small patch that inserts a needle into your skin. The device estimates your blood sugar every few minutes and sends the value to an app on your phone. You can track how various foods you eat alter your blood sugar.

Freeman wondered if the extra information about her blood sugar might give her insight into why she felt so sluggish and stuck in her weight loss.

On the first day, she uncovered a big clue: About two hours after lunch, her blood sugar nosedived below her baseline levels.

Dips trigger overeating

Studies have shown conclusively that these monitors greatly help people manage diabetes. But in 2024, the FDA approved the first continuous glucose monitors for people without diabetes. Now, two companies, Dexcom and Abbott, sell and market the devices to anyone who wants to track their blood sugar. They cost about $50 and last for a couple of weeks.

But scientists are still trying to figure out if — and how — these monitors could help people without diabetes. Can the data motivate people to eat a healthier diet by helping them learn how food affects their bodies?

One of the scientists leading this effort is Sarah Berry, a nutritionist at King’s College London. She’s also chief scientist at the company Zoe, which sells personalized nutrition plans that incorporate these devices.

In collaboration with Massachusetts General Hospital and Stanford University, Berry and her colleagues led two large studies in which thousands of people without diabetes wear continuous glucose monitors while they eat tens of thousands of meals.

After analyzing all of their data, Berry says one finding stands out: “A big proportion of people are what we call dippers,” she says.

If you’re a dipper, your blood sugar sometimes acts in a specific way: After eating carbohydrates, it rises quickly, and then about two to three hours later, it sometimes plummets low, below your baseline, or fasting, level.

“So you’ll have this big increase followed by this big crash,” Berry says. “Not everyone gets these dips, but we see that quite a high proportion of people do.”

These dips can trigger overeating, their study found, so it may make it harder to lose weight.

“If you are dipping, then you feel more hungry more quickly, and on average you tend to eat 80 calories more at the next meal and 320 calories more over a whole day,” she says.

But eating more wasn’t the only problem with dips. Berry’s team has found that the sugar crashes also correlated with a person’s mood. During a dip, people tended to feel less alert and more fatigued, she and her colleagues reported in the journal Nature Metabolism.

These conclusions line up with previous studies on people with diabetes, says Dalia Perelman, who’s a research dietitian at Stanford University and wasn’t involved in this research.

“When your blood sugar is high, people tend to be lethargic, fatigued, and thirsty,” Perelman says. “You’re just like, ugh.”

When your blood sugar is low, you’re jittery. You can have heart palpitations. And you become super hungry. “Low blood sugar gives your body very strong signals,” she says. “You really feel terrible,” which brings us back to Judy Freeman in Alpine, Texas.

The first day Freeman wore the glucose monitor, she ate lunch as usual. About two hours later, she started to feel horrible. “I had this really sinking feeling. It was a sort of anxiety or depression. I felt like if I don’t get up, I’m just going to stop breathing and die. It was so overpowering,” Freeman says.

When Freeman glanced at the monitor, she could hardly believe what she saw: “My blood sugar had shot up at some point, and then it plummeted down to the lowest point.”

This sinking feeling wasn’t new to Freeman. She’s had it from time to time. “I just never, ever thought it was in any way correlated with what I ate or anything like that.“

If you are concerned that your blood sugar may be fluctuating wildly and you want to even things out, here are three things you can try:

1. Put some clothes on those carbs

Don’t eat meals and snacks that consist mostly of carbohydrates, Perelman says. “Don’t eat naked carbs.”

Instead, eat them with protein and healthy fats. That means oils from vegetables, seeds and nuts, but also fats from fish. So add eggs to breakfast, canned fish for lunch or tofu for dinner.

On top of that, add more fiber — lots more. For that, the go-to ingredient is beans, says nutritionist Mindy Patterson at the Texas Woman’s University. “You really have to eat beans to get enough fiber in your diet,” she says. (Chia seeds are another great source of fiber.)

“Fiber and protein together put a speed bump on your digestion,” says clinical nutritionist Karen Kennedy. “They really stabilize your blood sugar.”

2. Sprinkle the carbs throughout the day

To prevent dips, you want your gut to slowly drip carbs into your blood, not douse it with a deluge of sugars, Perelman says. So don’t eat a bunch of carbohydrates all at one meal.

For preventing dips, “it doesn’t matter how many carbs you ate throughout the day,” she says. “It matters how many carbs you’ve had at each meal.”

3. Pay attention to what you eat first at a meal

With food, order matters, too. Eat the protein, fiber and fat first at a meal and the carbs last, Kennedy says.

Say you’re having a steak, salad and baked potato for dinner. “If you eat the salad and the steak first, and then the potato, you’ll see that you don’t have as much of a spike in blood sugar or as much of a drop afterwards,” she says.

If your blood sugar keeps a more even keel, then your mood and hunger will do the same.

And here’s the great part: You don’t need to buy a glucose monitor to figure this out, says Sarah Berry at King’s College London. Simply pay attention to how you feel about two hours after a meal. If you get moody, anxious or super hungry, you’re probably a dipper.

Edited by Jane Greenhalgh

Trump announces ‘major combat operations’ in Iran

Israel and the U.S. have launched strikes against Iran, with explosions reported in Tehran and air raid sirens sounding across Israel.

Trump says he is ‘not happy’ with the Iran nuclear talks but indicates he’ll give them more time

U.S. President Donald Trump said Friday he's "not happy" with the latest talks over Iran's nuclear program but indicated he would give negotiators more time to reach a deal to avert another war in the Middle East.

Bill Clinton says he ‘did nothing wrong’ with Epstein as he faced grilling over their relationship

Former President Bill Clinton told members of Congress on Friday that he "did nothing wrong" in his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and saw no signs of Epstein's sexual abuse as he faced hours of grilling from lawmakers over his connections to the disgraced financier from more than two decades ago.

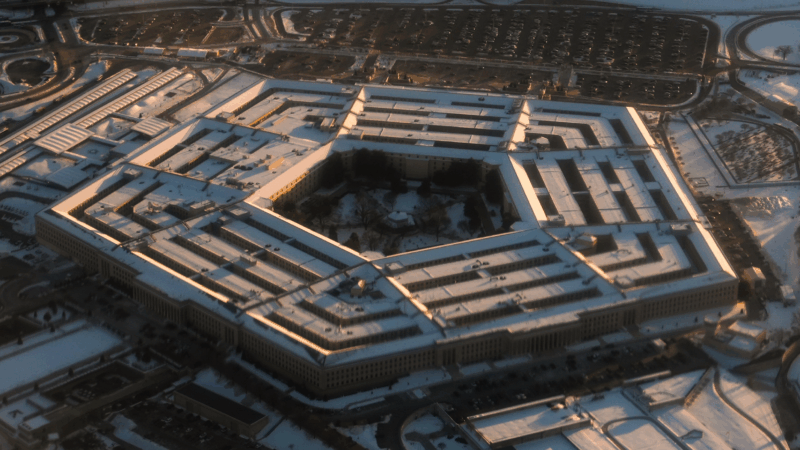

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.