An ancient archaeological site meets conspiracy theories — and Joe Rogan

GOBEKLI TEPE, Turkey — Tour guide Sabahattin Alkan herds curious tourists through the scorching afternoon heat, luring them with the promise of something far stranger than your typical vacation snap.

“Over here on the right, you see a spaceship landed recently,” he says with a grin.

He’s joking. Mostly. But more on that in a minute.

We’re in the Urfa plain, a dry, dusty stretch about 25 miles from the Turkish-Syrian border.

That “spaceship” is actually just a curved roof. But what lies beneath the dome has sparked decades of mystery, curiosity — and conspiracy.

“It’s quite an interesting place, actually,” Alkan assures his audience.

He’s talking about Gobekli Tepe, one of the oldest known archaeological sites on Earth, dating back nearly 12,000 years.

Alkan points to T-shaped limestone pillars carved with human arms, hands resting on stomachs, and wild animals: lions, foxes, boars, scorpions and birds among them.

Klaus Schmidt, the German archaeologist who led the site’s first major excavations in the 1990s, called Gobekli Tepe “the world’s oldest temple,” theorizing that it brought together nomadic hunter-gatherers from across the Middle East.

Today, that view has shifted. Some now interpret it as a ceremonial gathering site, while others suggest it functioned as a social hub where rituals helped bind together early communities.

Emilie Salvesen, a tour operator visiting the site, says the question of whether there was a spiritual component to the site still fascinates her.

“Did they experience the divine in the way that we might think of it today?” she asks, gesturing toward one of the inscribed pillars. “I imagine it was much more existential.”

The truth? Still mostly a mystery.

Scientists are regularly adjusting their hypotheses about the site’s intended purpose. And it’s not an easy investigation.

“Whatever we tell now, I don’t know if it will be accurate information or not, because maybe our idea will change in another 50 years,” Alkan says. “We’re trying to predict 12,000 years ago.”

But that uncertainty has thrown the door wide open for one specific group looking for answers: conspiracy theorists.

Conspiracy theories take root — with help from Joe Rogan

Graham Hancock, a British journalist and star of the controversial Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse, has theorized — without empirical evidence — that Gobekli Tepe was built by a “lost civilization” wiped out by an Ice Age cataclysm.

Once confined to the fringes, theories like Hancock’s have gained mainstream traction — thanks in large part to Joe Rogan, whose massively popular podcast has become a platform for alternative takes on science and history.

In November 2024, another Gobekli Tepe conspiracy theorist, Jimmy Corsetti, a YouTuber and self-described “ancient history investigator,” appeared on Rogan’s podcast, bringing with him a slew of speculations and wild theories about the site.

Among them, Corsetti accused archaeologists of intentionally dragging their feet and hiding key discoveries about the site.

“We’re talking about pillars buried in dirt. It’s 2024. Don’t tell me we don’t have the technology!” Corsetti told Rogan.

Corsetti accused archaeologists of moving slowly on purpose, perhaps to preserve the mystery and keep the curious tourists coming.

Only a small percentage of the site has been dug up since excavations began in the mid-1990s. And with Rogan’s platform behind them, theorists like Corsetti have helped turn that slow progress into a source of global suspicion.

A scientist responds

Lee Clare, an archaeologist who has led the excavation site for over a decade, has heard it all — including the outlandish theories.

Speaking from his office in Istanbul, with the Bosporus glinting behind him, Clare shrugs off the conspiracists.

“Some of these guys go to the site for half an hour and think they can explain the whole site,” he says of the budding conspiracy theorists.

When it comes to Gobekli Tepe, Clare says archaeologists aren’t hiding anything. They’re trying to protect it.

“You can’t just bulldoze a site to get everything out. That’s the wrong approach,” he says.

In other words, archaeology moves slowly for a reason. Every layer tells part of the story. And once you dig through each layer, it’s gone for good, as are its secrets.

“Why would I be so selfish as to dig the entire site … and take these possibilities away from future generations of archaeologists?”

Clare says he grew up playing with toy dinosaurs and always wanted to be an archaeologist. He never expected to end up the target of conspiracy theories. But here we are.

“It goes onto the personal level as well,” he says, which is why he deleted his social media accounts.

“I want to stay sane in this situation.”

12,000 years of storytelling

The real danger here isn’t just misinformation, according to Clare. It’s that these competing narratives risk drowning out the real story, the one scientists have spent decades trying to properly decode.

“There are a lot of narratives out there about Gobekli Tepe. The question is, whose narrative is correct? And I think we’ll never know.”

One of the few things scientists do know for sure?

Gobekli Tepe is proof that humans have been storytellers dating back at least 12,000 years.

The carvings on the T-shaped pillars — the lions, foxes and hands — they’re all stories.

We just don’t know what they say. Gobekli Tepe may be the first place humans come together to share meaning.

And like all good stories, this one’s still open to interpretation.

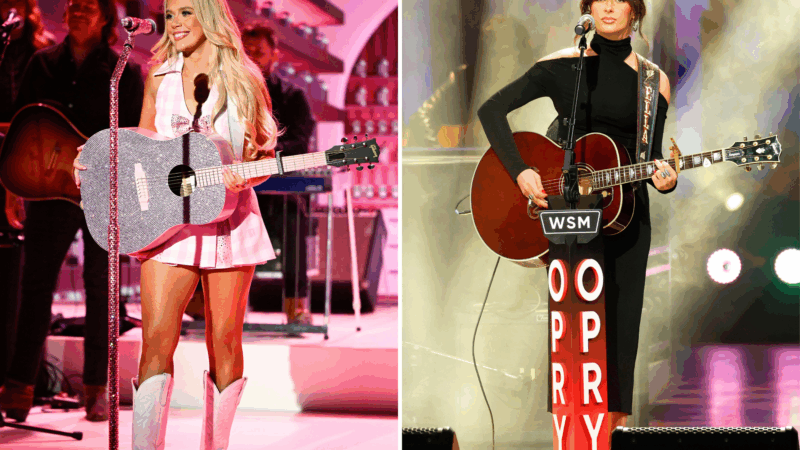

Between Megan Moroney and Ella Langley, country women rule the charts

It's a big week for women in country music — and, it turns out, for women whose songs are favored by women in figure skating.

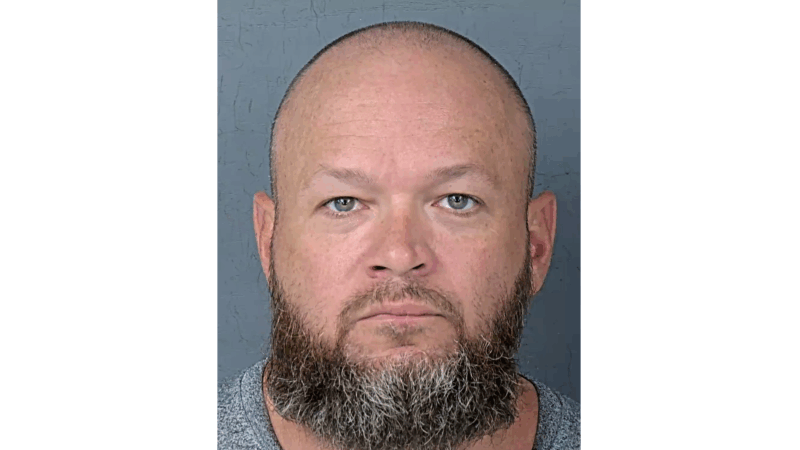

A Jan. 6 rioter pardoned by Trump was sentenced to life in prison for child sex abuse

Since receiving presidential pardons, dozens of former Capitol rioters have gotten into more legal trouble. In Florida, Andrew Paul Johnson was sentenced to life in prison for child sex abuse.

President Trump, Pam Bondi sued over sale of TikTok assets

The case, filed in a federal court in Washington, D.C., accuses the Trump administration of ignoring legislation designed to stop the spread of Chinese propaganda — and instead helping to broker a partial sale to businessmen close to Trump.

A rift between Spain and Trump widens over Spanish opposition to the Iran war

The Spanish government reiterated it would not let U.S. forces use two joint military bases in Spain as the U.S.-Israeli war in Iran escalates, widening a rift with the Trump administration.

Blackpink, modern K-pop’s trailblazing group, tries to find its way home

A new mini-album finds the world's biggest girl group in a tight spot: competing with its own legacy.

If you loved ‘Sinners,’ here’s what to watch next

So you loved best picture nominee Sinners. What should you watch next? We asked our audience to share their recommendations. They suggested Near Dark, The Wailing and other vampire horror films.