Alaska was once a full-fledged Russian colony. Now it’s hosting a U.S.-Russia summit

Russia lost a war in Crimea in the 1850s, leaving the country deep in debt. To ease that burden, Russia cut a real estate deal with the U.S. government, selling its colony of Alaska to the Americans.

Now, Presidents Trump and Russian leader Vladimir Putin will hold a summit Friday in Alaska to discuss another difficult and costly Russian war involving Crimea, one of the territories Russia has captured in its fight with Ukraine.

The decision to meet in Alaska appears mostly practical — it’s where the U.S. and Russia almost touch, separated by just 55 miles of the Bering Strait. Yet beyond geography, there’s also symbolism and a fascinating shared history.

Alaska was a full-fledged Russian colony from 1799 to 1867. Some Russians, including Kremlin envoy Kirill Dimitriev, are pointing to that period on social media, posting photos of Russian Orthodox Churches, with their onion domes, that were built in Alaska in the 19th-century and still stand.

“Some Americans might know that we bought Alaska from Russia, but they don’t know necessarily that it was a real colony there,” said Lee Farrow, a history professor at Auburn University at Montgomery and author of Seward’s Folly: A New Look at the Alaska Purchase.

“It wasn’t just a piece of territory that [the Russians] stuck a flag in. They had a strong presence in California as well.”

Farrow was referring to Fort Ross, an outpost the Russians established in what’s now part of Sonoma County in northern California.

Sold for a pittance

Russia’s decision to sell Alaska was motivated by its need to pay off war debts accumulated during the 1853-56 Crimean War, which Russia lost to the combined forces of Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire.

By this time, Russian hunters in Alaska had killed off most of the accessible bears, wolves, otters and other animals with valuable furs and pelts, and therefore the Russians saw little economic reason to stay.

Alaska seemed more a liability than an asset, and was extremely remote even by the standards of the Russian Empire. It was sometimes called “Siberia’s Siberia.”

After brief negotiations in the spring of 1867, the U.S. agreed to pay $7.2 million, which works out to 2 cents per acre. Alaska cover more than a half-million square miles and is by far the largest U.S. state.

The agreement came to be known as “Seward’s Folly,” a reference to Secretary of State William Seward who negotiated the deal under President Andrew Johnson.

Critics called Alaska a frozen wasteland, though Farrow said that description was inaccurate, then and now.

The deal attracted relatively little attention in the U.S. even though the country was rapidly expanding westward. The purchase provoked a bit of squabbling in Washington, and some newspapers argued against it, but it was never a major political issue, she said.

Little U.S. government investment

In its early days as a U.S. territory, Alaska and its indigenous people were mostly ignored. The U.S. government invested little, and the few Americans who ventured there tended to be missionaries or adventurers who were largely on their own.

Only decades later did Alaska begin to develop. Gold was discovered in 1896, Alaska became a state in 1959 and large oil reserves were found the 1950s and 60s.

There are some Russians today who think Alaska should be theirs. When Farrow went to Russia in 2017 after her book was published and spoke to groups, she could always count on a predictable question.

“In every audience there was at least one person who asked whether or not the United States had legitimately purchased Alaska,” she said. “There has been a very strong narrative in Russia that we either did not pay for it or it was a lease, and we should have returned it already.”

The Crimea link

While Alaska changed hands peacefully, Crimea is a territory that’s often been in conflict due to its strategic location as a peninsula jutting into the Black Sea.

Russia wanted full control of Crimea when it launched a war against the Ottoman Empire in 1853. The Russians expected a quick and easy victory, and did not expect Western powers to intervene.

But Britain and France joined the war against Russia, and the Russian army proved far less capable than Czar Nicholas I anticipated. Russia suffered a humiliating defeat.

In the 20th century, Crimea was part of the Soviet Union. But when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Crimea became part of newly independent Ukraine.

Fast forward to 2014. Putin sent Russian troops into Crimea as he launched his invasion of Ukraine, seizing the territory without any serious fighting.

Ukraine is demanding Crimea back, and regularly carries out air strikes with drones and missiles at the Russian forces there. Crimea will have to be part of any serious peace negotiations, and could feature in the Trump-Putin summit this Friday.

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Russia lost a war in Crimea in the middle of the 19th century. It left the country deep in debt, and to ease that burden, Russia cut a real estate deal with the U.S. and sold Alaska to the Americans. Now, Presidents Trump and Putin meet Friday in Alaska to discuss another difficult and costly Russian war involving Crimea. For more, we are joined by NPR’s Greg Myre. He is in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. Hey, Greg.

GREG MYRE, BYLINE: Hi, Mary Louise.

KELLY: So this summit, which is coming together really fast, why has Alaska been chosen as the site?

MYRE: The decision seems practical. It’s the place where the U.S. and Russia almost meet, separated by just 55 miles of the Bering Strait. But beyond geography, there’s also symbolism and a fascinating shared history. Alaska was actually a full-fledged Russian colony. Some Russians are pointing that out on social media, posting photos of Russian Orthodox churches with their onion domes that were built in Alaska in the 19th century. I spoke with Lee Farrow, a history professor at Auburn University at Montgomery and the author of a book on the U.S. purchase of Alaska.

LEE FARROW: Some Americans might know that we bought Alaska from Russia, but they don’t know necessarily that it was a real colony there – it wasn’t just a piece of territory that they had sort of stuck a flag in – and that they had a strong presence in California as well.

KELLY: And Greg, how good a deal was this for Russia to sell Alaska? It was then, and is now, very rich in natural resources.

MYRE: Well, not a good deal for the price they got – $7.2 million, which works out to 2 cents an acre when the Americans bought it in 1867. But the Russians saw it as an expensive outpost they couldn’t afford. Russian fur traders had been in Alaska for more than a half-century. They had killed off most of the bears and wolves and otters. The Russians didn’t see an economic reason to stay, and Alaska was so remote, even for Russia, it was sometimes called Siberia’s Siberia. But there are Russians today who think Alaska should be theirs. When Farrow went to Russia and spoke about her book several years ago, she always got the same question.

FARROW: In every audience, there was at least one person who asked whether or not the United States had legitimately purchased Alaska. There has been a very strong narrative in Russia that we either did not pay for it, or it was a lease and we should have returned it already.

KELLY: So interesting. What about the U.S. end of this? How was the purchase viewed here in the U.S. when it took place?

MYRE: Critics called it Seward’s folly, after Secretary of State William Seward, who negotiated the deal. They said the territory was a frozen wasteland. But Farrow says that description was inaccurate, then and now. At the time, the purchase didn’t really attract much attention outside of Washington. However, that said, the U.S. government didn’t invest much in Alaska, and the relatively few Americans who went there were missionaries or adventurers who were largely on their own. Only decades later did Alaska begin to develop. Gold was discovered in 1896. It became a state in 1959. And large oil reserves were found in the 1950s and ’60s.

KELLY: And in the few seconds we have left, I do want to focus on Crimea. It had this war in the 1850s. It is still being fought over today. Why is it so contested?

MYRE: Yeah, it’s a valuable piece of real estate on the Black Sea. Russia fought a war there in the 1850s against the Ottoman Empire, thinking they would win easily, but they didn’t. They lost. Fast forward to 2014. Crimea was part of Ukraine, but Putin seized it in an invasion, marking the start of the current war. Ukraine is demanding it back, and it’s expected to feature in the Trump-Putin summit this Friday.

KELLY: Thank you very much. NPR’s Greg Myre.

MYRE: Sure thing.

Guerilla Toss embrace the ‘weird’ on new album

On You're Weird Now, the band leans into difference with help from producer Stephen Malkmus.

Nancy Guthrie search enters its second week as a purported deadline looms

"This is very valuable to us, and we will pay," Savannah Guthrie said in a new video message, seeking to communicate with people who say they're holding her mother.

Immigration courts fast-track hearings for Somali asylum claims

Their lawyers fear the notices are merely the first step toward the removal without due process of Somali asylum applicants in the country.

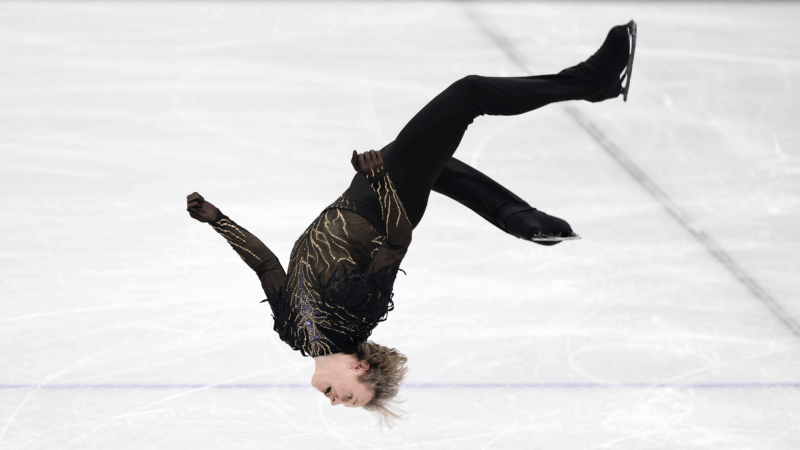

Ilia Malinin’s Olympic backflip made history. But he’s not the first to do it

U.S. figure skating phenom Ilia Malinin did a backflip in his Olympic debut, and another the next day. The controversial move was banned from competition for decades until 2024.

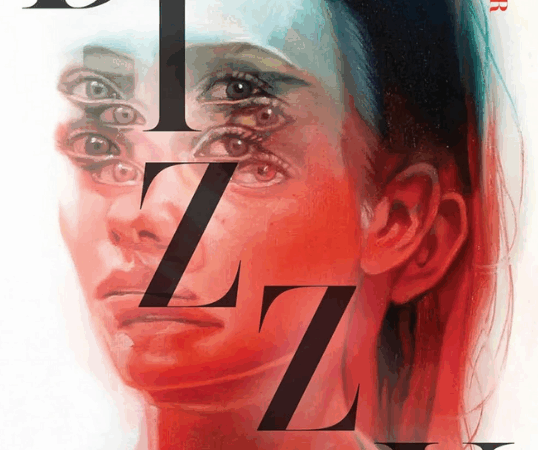

‘Dizzy’ author recounts a decade of being marooned by chronic illness

Rachel Weaver worked for the Forest Service in Alaska where she scaled towering trees to study nature. But in 2006, she woke up and felt like she was being spun in a hurricane. Her memoir is Dizzy.

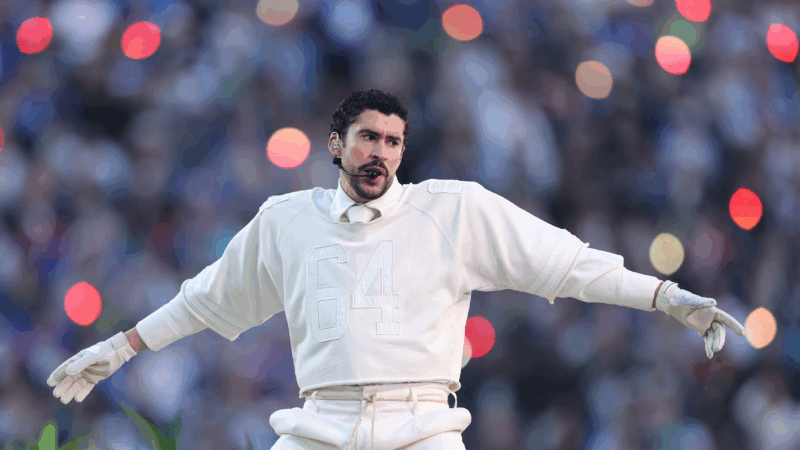

Bad Bunny makes Puerto Rico the home team in a vivid Super Bowl halftime show

The star filled his set with hits and familiar images from home, but also expanded his lens to make an argument about the place of Puerto Rico within a larger American context.