After Hurricane Katrina, evacuees changed Houston and the city changed them

HOUSTON – When Jermaine Moore needs a haircut, he looks for barbers from New Orleans. At a Shaving Grace barbershop in the southeast Houston area, he’s found one.

“New Orleans barbers cut different,” Moore said. “Our hair texture is different. This is not processed, this is my mother. But everybody can’t cut it.”

Moore is retired now. Before 2005, he lived a comfortable life as an IT professional in New Orleans. That changed after Hurricane Katrina destroyed his home in 2005.

While staying with family in Houston, he turned on the TV — and saw his house in the floodwaters.

“Yeah, saw my damn house on the news … watched everything float away, and looking down at that overnight bag, realizing that, and my truck outside, that’s all I got left,” Moore said.

After the storm, he went back to New Orleans to survey the damage, and that’s when he realized he would have to stay in Houston.

“You know what it’s like to stand in an American city and hear not a bird chirp, not a cricket … you hear nothing,” Moore said. “And you start to wonder, can I live here?”

Many residents of New Orleans were asking the same question. They went from finding temporary homes in Houston and other Texas cities to settling down for the long-term.

Twenty years later, they’ve changed Houston — and Houston has changed them.

‘Blessing and a curse’

Jermaine Moore met his wife in Houston. He also found a barber from New Orleans.

John “Speedy” Riddle started cutting hair about a decade after he arrived in Houston at the age of 15.

His family home also flooded during Katrina, and aside from short visits, his family never returned. Still, he finds meaning in the loss.

“I would have never got to live the life I’ve experienced up to 35 years old … if it wouldn’t have been for Katrina,” Riddle said.

Riddle was among as many as 6,000 students from New Orleans who came to the Houston Independent School District after Katrina interrupted the beginning of their school year.

Riddle and Moore knew each other for only a week before the haircut, but as they shared memories, it sounded like they had been talking for a lifetime.

“We seek each other out for the connection,” Moore said.

The memories of the evacuation still bring tears to Riddle’s eyes — but Moore says there’s more to the story than pain.

“Katrina hurt, but you’re supposed to find a blessing in a curse,” Moore said.

“I finished high school out here,” Riddle said, pausing the haircut. “I don’t think I would have — at 15, the life I was living in New Orleans, the things I got away with that my parents don’t know — I wouldn’t have made it. I wouldn’t have lasted this long.”

“Right, see, Houston for him at 15, showed him a completely different path,” Moore said. “He lost his community in New Orleans — the curse. The blessing — look at him.”

The overlooked evacuees

The evacuating population, like Houston, was diverse.

Bong Mui is a physician and was among the estimated 15,000 people from Louisiana’s Vietnamese community who came to Houston after Hurricane Katrina. His home and family medicine clinic flooded during the storm.

“I really love New Orleans, and I really wanted to come back,” Mui said, “but when I came back, and I saw that everything was completely destroyed … you know, I just couldn’t go back.”

He had fallen in love with the Crescent city when he attended his first Mardi Gras celebration in the 1970s. Over the next three decades, he was immersed in the city’s multiculturalism and special events.

“What I miss is the culture in New Orleans … the jazz music … the French, the Spanish flavor … I just love it,” Mui said.

He was already familiar with loss.

He was eight years old when Vietnam was split in 1954, and his family left everything behind during the move from the communist north to the south. 20 years later, he was studying in the U.S. when Saigon fell, and he wasn’t able to return.

After the hurricane in 2005, he was forced to start over for the third time. He brought his family to Houston and opened a new clinic. He felt at home among the larger Vietnamese community, which he said was more lively than the fishing communities of Louisiana.

“In New Orleans, the majority of them are fishermen and things like that, and there’s some cultural thing going on, but there’s nothing as compared to Houston,” he said.

The Vietnamese population in the Houston area has boomed — from just under 60,000 in 2005 to about 140,000 in 2025, according to the Pew Research Center.

“I’m still feeling a bit sad, but I’m happy with my life here,” Mui said. “I was able to be close to my siblings and close to my friends and, particularly, I’m happy with the growth of the Vietnamese community here.”

A changing Houston

After the hurricane, at least 100,000 people found refuge in Houston, according to Jim Elliott, co-director at the Center for Coastal Futures & Adaptive Resilience at Rice University in Houston.

“We have to keep in mind that this was the largest evacuation in terms of numbers and completeness in U.S. history,” Elliott said.

According to Elliott, it’s difficult to put an exact figure on how many evacuees came to Houston. He said the number could range from 100,000 to 300,000.

Those who came changed the culture.

“We have an incredibly diverse city, so what the New Orleanians did, I suspect, is they entered into this sort of gumbo, if you will, and began to add a little bit of this and a little bit of that,” Elliott said.

It’s also hard to say how many Katrina evacuees are still in Houston 20 years later.

But their cultural contribution is undeniable — from cajun flavors at crawfish boils to the widely popular White Linen Night block parties in the Houston Heights neighborhood.

(Justin Doud | Houston Public Media)

Two decades after Hurricane Katrina, those New Orleanians — including Jermaine Moore and John “Speedy” Riddle — see Houston as a place of new beginnings, opportunity and community.

They also see more of New Orleans in Houston.

“The good part that has changed — our influence. I can find daiquiris now,” Moore said, as Riddle enthusiastically agreed. “I can find food like home now … Couldn’t find that 20 years ago, so there’s the change. I can find more remnants of home, actual home. Twenty years ago, we were a fish out of water.”

They say with the curse of losing home, there’s also the blessing of finding — and changing — Houston.

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Twenty years ago, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, there was an exodus from New Orleans. At least 100,000 people who left found refuge in Houston. Many of them stayed there and helped to reshape the largest city in Texas. Houston Public Media’s Dominic Anthony Walsh reports.

(SOUNDBITE OF CLIPPERS BUZZING)

DOMINIC ANTHONY WALSH, BYLINE: When Jermaine Moore needs a haircut, he looks for barbers from New Orleans. At A Shaving Grace Barbershop in the southeast Houston area, he’s found one.

JERMAINE MOORE: New Orleans barbers cut different. Our hair texture is different. This is not processed. This is my mother, but everybody can’t cut it.

WALSH: Moore is retired now. Before 2005, he lived a comfortable life as an IT professional in New Orleans. That changed after Katrina destroyed his home. While staying with family in Houston, he turned on the TV and saw his house in the floodwaters.

MOORE: Yeah, I saw my damn house on the news. Watched everything float away, and looking down at that overnight bag, realizing, that and my truck outside, that’s all I got left. Yeah.

WALSH: He says he realized he would have to stay in Houston after he went back to New Orleans to survey the damage.

MOORE: You know what it’s like to stand in an American city and hear not a bird chirp, not a cricket? You hear nothing. It is the smell of absolute death. I’ve never smelled anything like that in my life. And you start to wonder, can I live here?

WALSH: Back then, many residents of New Orleans were asking the same question. Exactly how many people came to Houston is hard to say, with researchers and former city officials putting the number anywhere from 100,000 to 300,000. Tens of thousands are estimated to remain. Twenty years later, they’ve changed Houston, and Houston has changed them. Jermaine Moore met his wife in Houston. He also found a barber from New Orleans.

JOHN RIDDLE: You don’t want no bald. You want a light fade?

MOORE: Yeah.

RIDDLE: Need a light fade? I got you.

MOORE: Can you get me here? Thank you.

RIDDLE: For sure.

(SOUNDBITE OF CLIPPERS BUZZING)

WALSH: John Speedy Riddle started cutting hair about a decade after he arrived in Houston at the age of 15. His family home also flooded during Katrina. Aside from short visits, his family never returned. Still, he finds meaning in the loss.

RIDDLE: I would’ve never got to live the life I’ve experienced up to 35-years-old if it wouldn’t have been for Katrina.

WALSH: He was among as many as 6,000 students from New Orleans who came to the Houston Independent School District, with thousands more attending schools outside the city after Katrina interrupted the beginning of their school year. The memories of the evacuation still bring tears to Riddle’s eyes. But Moore says there’s more to the story than pain.

(SOUNDBITE OF CLIPPERS BUZZING)

MOORE: Katrina hurt, but you’re supposed to find a blessing in a curse.

RIDDLE: I finished high school out here. I don’t think I would’ve at 15. The life I was living in New Orleans, the things I got away with that my parents…

MOORE: No.

RIDDLE: …Don’t know, I wouldn’t have made it. No, I wouldn’t have lasted this long.

MOORE: Right. See, Houston, for him at 15, turn around. Showed him a completely different path.

RIDDLE: It showed me childhood.

MOORE: Yeah, he lost his community in New Orleans. The curse. The blessing. Look at it.

RIDDLE: I found a tribe here.

MOORE: Right.

RIDDLE: You know what I’m saying?

MOORE: Blessing in a curse.

WALSH: Sociologist Jim Elliott with Rice University, also left after Katrina and eventually settled in Houston. He says the cultural impact of the evacuees is undeniable.

JIM ELLIOTT: We have to keep in mind that this was the largest evacuation in terms of numbers and completeness in U.S. history.

WALSH: Exactly how large? It’s hard to know. And it’s difficult to say how many stayed long term. Either way, those who remained changed the culture, bringing to Houston New Orleans-style jazz, events like the White Linen Night block parties and Cajun twists on existing dishes like gumbo and crawfish boils.

ELLIOTT: What the New Orleanians did, I suspect, is they entered into this sort of gumbo, if you will, and began to add a little bit of this and a little bit of that.

WALSH: Twenty years later, tens of thousands of New Orleanians – including Jermaine Moore and John Riddle – see Houston as a place of new beginnings, opportunity and community. They also see more of New Orleans in Houston.

MOORE: The good part that has changed? Our influence. I can find daiquiris now.

RIDDLE: Yeah.

MOORE: I can find food like home now.

RIDDLE: I can go to H-E-B…

MOORE: Twenty years ago…

RIDDLE: …And buy Blue Plate mayonnaise and Patton’s hot sausage…

MOORE: OK.

RIDDLE: …From Fiesta.

MOORE: I know that sounds stupid, but y’all don’t understand how important that is to us. I can find more remnants of home, actual home. Twenty years ago, we were fish out of water.

WALSH: They say with the curse of losing home, there’s also the blessing of finding and changing Houston.

For NPR News, I’m Dominic Anthony Walsh in Houston.

Nancy Guthrie search enters its second week as a purported deadline looms

"This is very valuable to us, and we will pay," Savannah Guthrie said in a new video message, seeking to communicate with people who say they're holding her mother.

Immigration courts fast-track hearings for Somali asylum claims

Their lawyers fear the notices are merely the first step toward the removal without due process of Somali asylum applicants in the country.

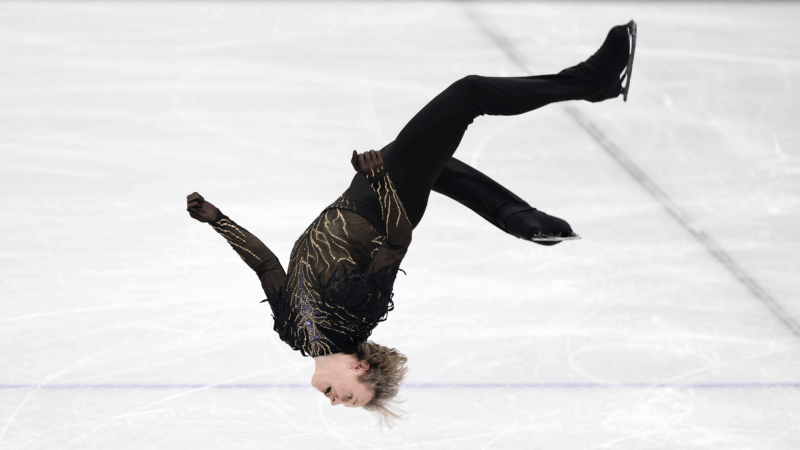

Ilia Malinin’s Olympic backflip made history. But he’s not the first to do it

U.S. figure skating phenom Ilia Malinin did a backflip in his Olympic debut, and another the next day. The controversial move was banned from competition for decades until 2024.

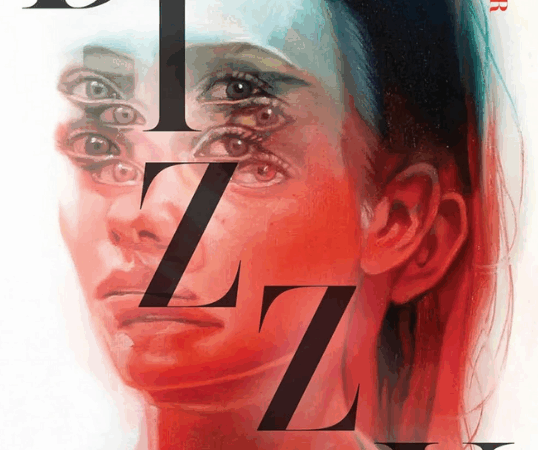

‘Dizzy’ author recounts a decade of being marooned by chronic illness

Rachel Weaver worked for the Forest Service in Alaska where she scaled towering trees to study nature. But in 2006, she woke up and felt like she was being spun in a hurricane. Her memoir is Dizzy.

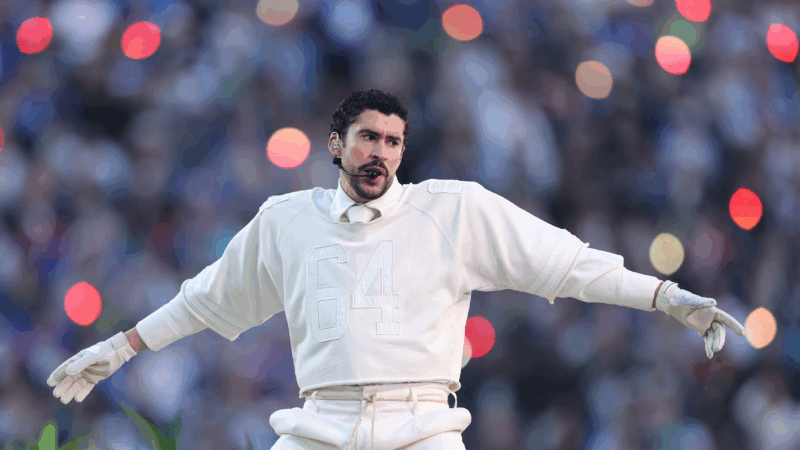

Bad Bunny makes Puerto Rico the home team in a vivid Super Bowl halftime show

The star filled his set with hits and familiar images from home, but also expanded his lens to make an argument about the place of Puerto Rico within a larger American context.

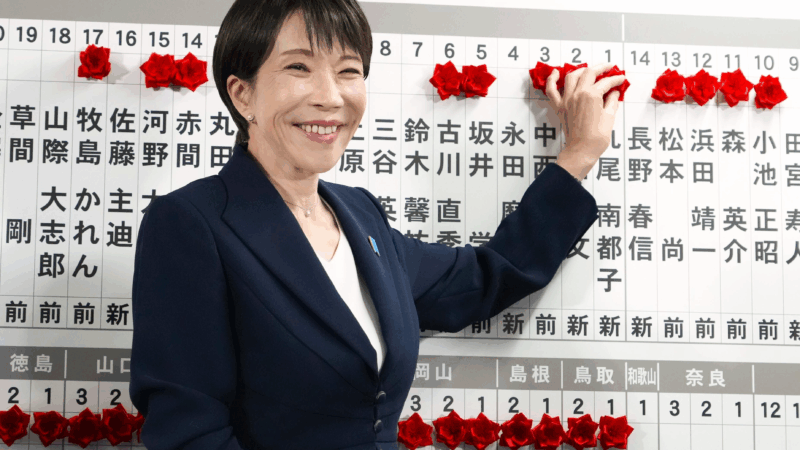

Japan’s Takaichi to pursue conservative agenda after election landslide

Japan's first female Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi, brought the ruling Liberal Democratic Party its biggest-ever electoral victory, fueling her ambitions to pursue to a political agenda which she says could "split public opinion."