A teen nicknamed ‘God’s influencer’ is becoming the first millennial saint

ASSISI, Italy — In the silence of St. Mary Major Church in this central Italian hill town, a tour group of Polish teenagers files past a glass-sided tomb to look in on a child of their own age. His face and hands are reconstructed with silicone. He’s wearing jeans, a tracksuit top, and Nike sneakers. He is Carlo Acutis, the first millennial saint and known in the Catholic Church as “God’s influencer.”

On Sunday, Acutis, who died of leukemia when he was 15 years old in 2006, will be canonized in a ceremony at the Vatican presided over by Pope Leo XIV that is expected to be attended by thousands of devotees of this first saint of the “digital age.” Witnessing the rise of the internet, cellphones and social media as a teenager, Acutis harnessed these new powers of communication and coded a website to catalogue and promote eucharistic miracles. (Eucharistic miracles involve the Catholic sacrament of Communion.)

The sainthood of a contemporary has inspired enthusiasm among Catholics. The Blessed Acutis receives prayers and requests for miracles from around the world — often, fittingly, through the internet. His tomb is livestreamed 24/7 via a webcam. Devotees post messages to him in comments under online prayer videos on YouTube for Acutis. “Blessed Carlo, thank you so much for interceding for my prayer, it’s a miracle that I got a positive pregnancy test at the age of 43,” reads one. “Blessed Carlo — heal me with my arthritis,” reads another. “My cousins lost their dog and I prayed to Carlo Acutis so they might find it, and miraculously they did.”

Assisi is home to the tombs of St. Francis and St. Clare. But now, for many of the nearly 1 million visitors who church officials say came to the diocese last year, Acutis is part of the pilgrimage. Shops sell his memorabilia — the boy’s face encased in a corona of holy light is on mugs, keychains, rosaries. Online, a wooden statue of Acutis sells for more than $14,000. The Catholic Church has had to ask police to crack down on the sale of purported locks of his hair.

It can take hundreds of years to be recognized as a saint. For Acutis, it has happened so quickly that his mother and father are in the rare position of being alive to witness it.

“Of course it doesn’t mean that his mother is a saint,” quips Antonia Salzano, when NPR asked how she feels about her son’s canonization. “But it’s a responsibility.”

A responsibility that seems to drive and consume Salzano. The 58-year-old, dressed in black, meets NPR in the garden of a villa just a few miles from the church in Assisi where lines of visitors file past her son’s tomb.

The interview is one of countless media appearances Salzano has made, protecting and promoting her son’s image at the time that officials in the Vatican deliberated on whether to progress the application for his sainthood.

She rages at an article published in The Economist that quotes friends of Acutis who don’t recall the teenager seeming particularly devout. (She also questions if this NPR reporter and the accompanying photographer are Catholics, implying it’s to establish whether she can “trust” her interviewers.)

“I speak to stop nonsense spreading around about Carlo,” she says. “I want to make sure everything is said about him in the proper way. Carlo is an instrument of God.”

Acutis was born on May 3, 1991, in London and then moved with his Italian parents to Milan as a young boy. Salzano says he uttered his first words at 3 months old, and that by 5 months, “he could speak.” She would call him “little Buddha,” knowing there was “something special” about her son. In infancy, she says Acutis tried to give away new toys, saying he didn’t need so much. As a boy, he asked his parents to bring blankets to the poor people on the streets of Milan where they lived. She says from the age of 7 he “insisted” on attending Mass every day. At 9 years old he read “university-level texts” on computing, and taught himself several coding languages.

Salzano’s memoir, My Son Carlo, describes the agonizing days after he fell suddenly ill, when he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of leukemia and died soon thereafter. Salzano, who was 39 at the time, says she didn’t expect to be able to have more children. Until one night, when she was 43, Acutis appeared to her in a dream. “He said: ‘Don’t worry, you will become a mother again,’ ” she recalls. One month later, she became pregnant with twins. “This was his present to his parents,” she says. “Each day we receive news of a miracle by Carlo; of a healing. So of course, the parents get a miracle too.”

Miracles are a prerequisite for being declared a saint in the Catholic Church. For Acutis, the Vatican recognizes two: the healing of a 4-year-old Brazilian boy with a serious pancreatic malformation, and the sudden recovery of a 21-year-old Costa Rican woman after a near-fatal bicycle accident. Vatican officials say both the mother of the young boy and the injured woman had prayed to Acutis for help.

The politics of becoming a saint

To become a saint, the Vatican’s department of the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints must assess a candidate’s spirituality in life and their influence after death. It is a complex posthumous trial. Groups supporting a candidate for sainthood campaign to publicize their holiness.

For Acutis, the official process began in 2012, when the archdiocese of Milan opened a “cause” for his beatification. Salzano, Acutis’ mother, has said in media interviews that the family supported the costs leading to his canonization. These can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. A postulator is then appointed in Rome to follow the application and bureaucratic procedures in the dicastery. (Acutis’ postulator is Nicola Gori, a writer who authored the book Carlo Acutis: The First Millennial Saint.)

Archbishop Domenico Sorrentino in Assisi, tells NPR that Acutis’ lightning-fast rise is a confluence between God’s will and the needs of the Catholic Church in this particular era. Acutis is a saint for young people, just at the time that the church is trying to bring more of Generation Z to Mass. “Young people nowadays are so difficult,” Sorrentino says. “The model of a young man who found his joy, the sense of his life in Jesus, is so very important.”

The cult of Acutis

Acutis’ modern tomb contrasts with its surroundings of ancient stone and remnants of frescoes in the 11th century church in Assisi. Like something from science fiction, the casket where the boy lies is made to look like it’s levitating. The smooth stone case is made to look as if it “hovers” against the wall, sheared off a rock base. Below, a white light shines out from behind the casket.

When NPR visited, João Claro Pinto knelt with tears streaming down his face as his wife held their 15-month-old toddler to the glass. The family had come from Portugal to thank Acutis. “Last year my son was hospitalized with meningitis,” he explained afterward. “I prayed very hard to Carlo. My son was saved.”

As some faithful visit Assisi to see some of Acutis’ remains and reconstructed face, other parts of the boy have been traveling the globe as relics. Anthony Figueiredo, a British priest with the Diocese of Assisi, handles a sliver of the boy’s pericardium — the sac that surrounds the heart — that is touring the world as a religious relic. He tells NPR that he and his team have taken the pericardium, which is encased in a gold and glass frame, to nearly 25 countries in two years. It is always hand carried on the plane, he says. “We would never put a saint in the hold.”

The trips draw “thousands” of worshippers, Figueiredo says. In one visit to a parish in Ireland, he recalls that a crowd of over 15,000 people came — many of them hoping to come into contact with the encased pericardium to feel close to Acutis. “People can see, touch and kiss the relic as they wish, according to the local norms,” he says. “We believe as Catholics that saints are alive in heaven. And so they intercede before Jesus in heaven, before God.”

To move the pericardium across international borders, Figueiredo has to secure special clearances from customs to transport human remains. But he says this has not been difficult to do. And during a recent trip to the United States, they arrived at John F. Kennedy airport to find guards waiting for them, “wanting to be blessed with the relic.”

This year, more parishes have requested a visit than Figueiredo’s team can get to. The pericardium relic is expected to be in Rome for the day of Acutis’ canonization.

Having been born in this era, Figueiredo says Acutis “takes us under his wings, knowing us.”

The saint of youth, he says, “gives people hope.”

Transcript:

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

Tomorrow, an Italian boy who died in 2006 becomes the Catholic Church’s first millennial saint – in other words, the first saint from a generation of smartphones, social media and the internet. Just 15-years-old when he died, Carlo Acutis had been nicknamed God’s influencer or the Saint of the internet for how he promoted Catholic miracles online. He’ll be canonized by Pope Leo at a mass in St. Peter’s Square, attended by tens of thousands of faithful. NPR’s Ruth Sherlock reports on Acutis’ family and the people from around the world who are visiting the tomb of this modern-day saint.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Singing in non-English language).

RUTH SHERLOCK, BYLINE: Assisi, the Italian hilltop town has long been a draw for the Catholic faithful.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Singing in non-English language).

SHERLOCK: This woman singing gave up a life in Germany to busk here and feel closer to God.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Singing in non-English language).

SHERLOCK: This is a town of religious art and Catholic saints, the birthplace of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Clare, who both founded religious orders. Shops burst with rosaries for worship and mugs with saints’ faces.

UNIDENTIFIED GROUP: (Praying in non-English language).

SHERLOCK: And now it is also the home to the Catholic Church’s first millennial saint.

UNIDENTIFIED GROUP: (Praying in non-English language).

SHERLOCK: In this 11th century church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Carlo Acutis’ tomb jars with its surroundings of old stone and broken frescoes. His angular casket has been made to look like it’s levitating, as if it’s ripped off from a rougher stone slab below, and now hovers higher up the wall with a bright white light emanating from it.

(SOUNDBITE OF BEADS CLINKING)

SHERLOCK: A visitor from the Philippines collects fistfuls of prayer beads from her bag and, to bless them, touches them to the glass paneled side of Acutis’ tomb.

Through the glass, you can see the body of Carlo Acutis. He’s dressed like an ordinary teenager, in jeans and sneakers and a hoodie. And his face and hands have been reconstructed with silicon, so he looks perfectly preserved.

(CROSSTALK)

SHERLOCK: Born in 1991 in London and raised in Milan in Italy, Acutis was just 15-years-old when he died of leukemia in 2006.

MARY KAVANAGH: My friend had a son who was christened in the same baptismal font as Carlo in London.

SHERLOCK: Outside the church, Mary Kavanagh says she’s come to his tomb to pray for all young people and, in particular, those who feel lost.

KAVANAGH: I think Carlo, for me, kind of summarizes someone who, at such a young age, we’re so sure of what he believed in.

SHERLOCK: Yeah.

KAVANAGH: (Crying) And I think there’s so many – sorry – young people who…

SHERLOCK: It’s OK.

KAVANAGH: …Who just get lost…

SHERLOCK: Yeah.

KAVANAGH: …Who just don’t know who they are, where they’re going, what they’re for. And I think it’s so amazing to see all these young people coming to visit Carlo because I think he’s a great inspiration in these times.

SHERLOCK: It can take hundreds of years to be recognized as a saint. For Acutis, though, it happened so quickly that his parents are still alive. I meet his mother, Antonia Salzano, in the garden of a villa just outside of Assisi.

What’s it like to be the mother of a saint?

ANTONIA SALZANO: Of course, it doesn’t mean that the mother is saint, but it’s a responsibility.

SHERLOCK: For years now, Salzano has been speaking with journalists, promoting her son and his life. She remembers him as a very advanced child.

SALZANO: Three months, first word. Five months, he already was able to speak, and he was also a genius of the computer.

SHERLOCK: By nine years of age, he was learning multiple computer coding languages. And he was an unusual child also for his faith. Salzano, who was not particularly religious back then, says her son would ask her, his grandmother or his nanny to take him to church every day.

SALZANO: Each day, the mass, till he died.

SHERLOCK: Acutis put his technical skills to use to make a website where he catalogued Eucharist miracles. Salzano speaks about Acutis in the present tense. It’s clear she still feels close to him and believes he’s interceding to help people from beyond the grave, including her.

SALZANO: When he died, I was 39 years old.

SHERLOCK: At that age, Salzano thought that perhaps she couldn’t have any more children. But then, aged 43, Acutis came to her in a dream, promising she would be a mother again. A month later, she became pregnant with twins.

SALZANO: It was a gift of Carlo because he does a miracle. Each day, we receive the news of a miracle.

SHERLOCK: To become a saint, the Vatican says, at least two miracles have to occur after death that can’t be explained by science. In Acutis’ case, the Vatican cites the recoveries of a 4-year-old Brazilian boy with a serious pancreatic malformation and a 21-year-old Costa Rican woman who suffered a bicycle accident. The mother of the young boy and the injured woman had both prayed to Acutis for help.

DOMENICO SORRENTINO: The miracles, which are the guarantee that comes from God.

SHERLOCK: Domenico Sorrentino is the archbishop of Assisi, and he says, saints are from God, but who becomes a saint is also political.

SORRENTINO: This depends on the strategy of the church to put in the eyes of the people saints that could speak to our sensitivity.

SHERLOCK: The right saint for the right era – Acutis lived during the rise of the internet, of mobile phones and of social media, and now the church hopes his canonization will bring more young people to the faith.

ANTHONY FIGUEIREDO: Whenever we take the heart relic, thousands come.

SHERLOCK: Monsignor Anthony Figueiredo with the Diocese of Assisi is in charge of the official relic of Acutis. It’s Acutis’ pericardium, the heart’s protective coat, kept in an ornate case.

FIGUEIREDO: It’s a beautiful gold reliquary with a glass casing. So people who come can certainly see, can touch, can kiss the relic as they wish and according to local norms.

SHERLOCK: The relic has been to some 25 different countries in two years. On planes, it is always hand carried.

FIGUEIREDO: We would never put a saint in hold.

SHERLOCK: Figueiredo says having a modern saint gives people hope.

FIGUEIREDO: He takes us under his wings, knowing us in this age.

SHERLOCK: And he says, in this era, people need hope. Ruth Sherlock, NPR News, Assisi, Italy.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

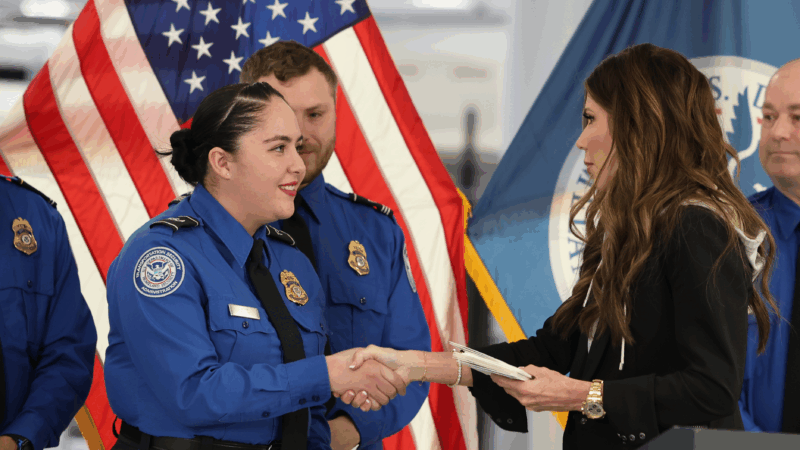

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.