A new biography zeroes in on Lin-Manuel Miranda’s superpower

The word “genius” is regularly used for absurdly talented artists and writers. Take Lin-Manuel Miranda, a composer, lyricist, director and actor best known for creating the musical Hamilton. Not only has he won a “genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation, but he’s been called a genius in publications like Smithsonian Magazine, The Guardian and BuzzFeed.

Genius implies something solitary, and we often think of it as innate. Even so, Miranda wasn’t the best student when he was young; teachers weren’t swooning over his early promise. As Miranda told Daniel Pollack-Pelzner, the author of a new biography, Lin-Manuel Miranda: The Education of an Artist: “I was never the brightest student at Hunter College Elementary School, but I was good at making up songs, and I was good at making kids laugh, which is the only currency that matters when you are surrounded by people who are much smarter than you.”

Pollack-Pelzner, a writer for The New Yorker and a visiting scholar at Portland State University, says that although Miranda is undeniably talented and works very, very hard, his superpower is that he cultivates, collaborates with — and is constantly learning from — a large group of creative friends.

Pollack-Pelzner’s new book traces Miranda’s career from elementary school musicals, to writing and starring in Disney movies, to his concept album based on the cult-classic film The Warriors.

Miranda, who has Puerto Rican and Mexican heritage, grew up in a neighborhood at the top of Manhattan, surrounded by the Latino community he extols in his Tony award-winning musical In the Heights. But he went to school on the snootier, more white Upper East side, which was a tremendous adjustment. He struggled at first — math made him anxious, he disliked his nose, as Pollack-Pelzner writes — but, like a lot of people who feel like they don’t fit in, he gravitated toward theater.

Theater gave Miranda a place to try out his ideas, and he reached out to talented people he knew to help get them up on stage. Pollack-Pelzner writes that Miranda collects people who can teach him something, keeping many of them as lifelong collaborators: one particular friend taught him a bit about composing music; others helped him learn to freestyle. When he was hired to translate some lyrics in West Side Story into Spanish for a new Broadway production, he met the late composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim — and Sondheim became a mentor, helping him navigate the world of musical theater.

His family has also been a strong source of support. His mother Luz Towns-Miranda, a therapist, helped him process the big feelings that he’d later turn into songs, Pollack-Pelzner explains. His father, Luis A. Miranda Jr., a political strategist, helped him with everything from Puerto Rican slang to financial support for his productions. Miranda’s wife, Vanessa Nadal, has also contributed to his successes — she prodded him to include a song for the women in Hamilton, which became “The Schuyler Sisters.”

Miranda regularly publicly thanks and praises those who have supported and taught him, and who have contributed their ideas and talents to his work. That they feel validated by him is evident from the many thoughtful, warm quotes in the book. Pollack-Pelzner says he interviewed more than 150 people and met with Miranda himself more than a dozen times. Miranda shared with him “early scripts, rough recordings, and grainy videos of sixth-grade musicals, high school one-acts, college projects and pre-Broadway experiments,” he writes.

Pollack-Pelzner is at his strongest when he delves into the fascinating nitty gritty of the collaborations that help productions come together. People call Miranda a genius because he seamlessly mashes seemingly disparate ideas together (the American Revolution and hip-hop!) to make work that is sparkling with joy, emotionally resonant and blazingly new. And Pollack-Pelzner brings us so deeply into this work — tracing the birth of individual songs line by line — that we feel the zing of creation.

But this is not a hagiography. Pollack-Pelzner is frank about Miranda’s shortcomings, such as the time when the original cast of Hamilton was fighting to share 1% of the profits for the show’s runaway success. Like many original casts, they had helped foster its development. Miranda — who was both a cast member who received a pay check and a creator who received royalties — tried to stay out of it, instead of advocating for them with the lead producer, and he felt “othered” by the cast, Pollack-Pelzner explains.

The book also wades into the murk around Miranda’s attempt to influence politics.

Miranda raised millions of dollars for relief after Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico in 2017; he wanted to raise more by bringing Hamilton to the University of Puerto Rico, his father’s alma mater. But in 2016, he had asked Congress in an op-ed to support a bill that would restructure the territory’s significant debt. The University of Puerto Rico had been particularly negatively affected — budgets were cut, employees threatened to strike and students protested.

“Boy, is Hamilton a bad fit for raising money for Puerto Rico,” Miranda is quoted as saying in the book. “It’s singing about the financial system that traps Puerto Rico in debt.”

The show had to be moved to a different venue and Miranda wound up swearing off politics.

And yet, it was still a homecoming. When he sang, “My name is Alexander Hamilton,” the book recounts, “Two thousand people rose in a standing ovation that seemed like it would last forever. ‘It was the first time I felt a cheer,’ he said after the show. ‘I felt my hair move.'”

But of course, he didn’t keep all the praise for himself — at the end of the show, he brought his father onstage to thank him.

Pollack-Pelzner uses these details to treat Miranda as the creator he is — enthusiastic, vulnerable, ambitious, innovative, fallible — instead of as a mere celebrity. A different biographer might have used this as an occasion for dishy name dropping, but Pollack-Pelzner builds the case that Miranda is so successful because he is able to take all the contradictions of who he is, what he’s experienced, who he knows, and combine them into work that speaks to so many. And it could be that this talent is, in fact, genius.

A split Senate votes against measure to constrain Trump’s authorities in Iran

Democrats in the Senate were facing an uphill climb Wednesday in their push to restrain President Trump's ability to wage war against Iran.

WATCH: How traffic dried up in the Strait of Hormuz since the Iran war began

The effective closure of the Strait of Hormuz is "about as wrong as things could go" for global oil markets. Iran achieved it not with a naval blockade, but with cheap drones.

As Mississippi waits to spend opioid settlement funds, children and families suffer

Mississippi will receive more than $400M to fight the opioid epidemic. So far, officials haven't directed it toward programs that support addiction recovery.

Alabama’s new state climatologist takes the reins

The controversial John Christy is retiring as Alabama’s state climatologist. Lee Ellenburg now assumes the role and is already making a few changes, including declaring that climate change is real and caused by humans.

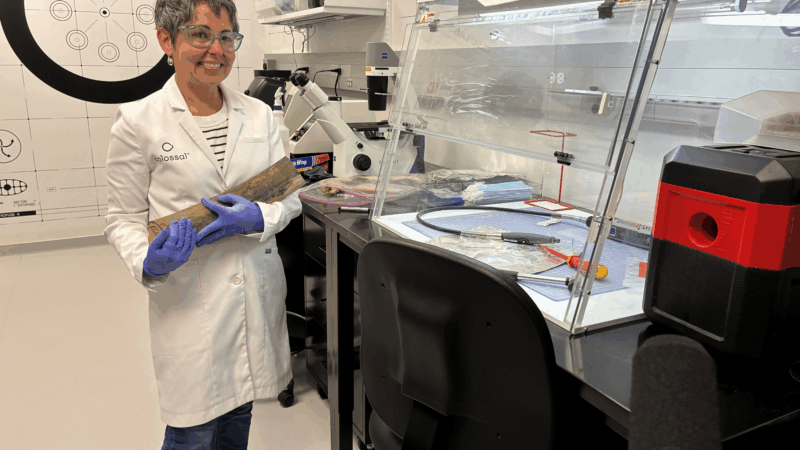

Colossal Biosciences breeds controversy while trying to revive mammoths

A Texas biotech company is trying to bring mammoths and other extinct creatures back to life. The science is as intriguing as the ethical questions are thorny.

Mundane, magic, maybe both — a new book explores ‘The Writer’s Room’

Why are we captivated by the spaces where where authors write? Katie da Cunha Lewin set out to explore "The Hidden Worlds That Shape the Books We Love."