‘A lid on a pot’: How does a heat dome work?

A heat dome is bringing oppressive heat to the eastern half of the contiguous U.S., with forecasters warning people in those areas to take precautions to cope with extreme high temperatures. The phenomenon occurs when high pressure lingers and traps warm air near the surface, while also suppressing clouds and precipitation.

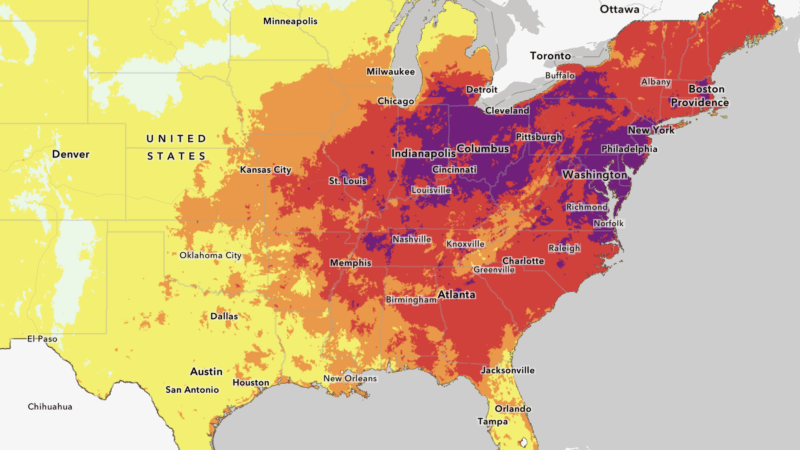

Heat warnings and advisories “extend from the Lower Mississippi Valley and Midwest to the East Coast, affecting nearly 160 million people,” the National Weather Service said Tuesday morning.

Boston, Mass., hit 100 degrees early Tuesday afternoon. Temperatures soared past 95 degrees in many parts of Pennsylvania, with heat index values above 100 degrees expected in cities such as Philadelphia, Lancaster and Pittsburgh. In central North Carolina, forecasters expected heat index values up to 115 degrees.

What is a heat dome?

“It almost acts like a lid on a pot,” the National Weather Service’s Alex Lamers told NPR, discussing how a heat dome works. Lamers is the operations branch chief at the Weather Prediction Center.

“If you’ve made grilled cheese in a pan and you put a lid on there, it melts the cheese faster because the lid helps trap the heat,” Lamers said. “It’s a similar concept here: You get a big high-pressure system in the upper parts of the atmosphere and it allows that heat to build underneath over multiple days.”

That’s right: days, or even weeks.

A heat dome is basically a massive area of high pressure and warm air that “parks” over a region. The exact location is generally linked to the jet stream — and right now, the jet stream is moving sharply to the northeast, from the upper Baja California peninsula to a spot just west of Lake Michigan. That allows a heat dome to persist in much of the eastern half of the U.S.

When a heat dome sits over a large land area, it can form a sort of feedback loop, Lamers said, adding that high pressure typically means dry weather, which can help drive the heat even higher.

Extreme heat has shattered records in many parts of the U.S. in recent years, and scientists warn that we’re likely to see even more dangerous temperatures in the future — a trend linked to human-caused climate change. Both 2023 and 2024 were designated the hottest years ever recorded.

Health alerts again mark the start of summer

People living in the Midwest and Northeast can be forgiven for having a sense of weather déjà vu: Almost exactly one year ago, a heat dome brought record high temperatures to those areas, sending summer to a scorching start.

The current bout of extreme heat is expected to persist in the Midwest through this week, bringing temperatures that are far above average. But a cold front should bring relief to the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic later this week, the NWS said.

While record highs will make headlines, warm low night-time temperatures will make it hard for people to cool down and recover when they finally get a break from the sun.

Experts warn that the oppressive heat could pose particular risk to children and people with existing health issues — but the weather service warns, “This level of heat can be dangerous to anyone without adequate cooling and/or hydration.”

Anyone who has to be outside should consider advice from Dr. Jess Weisz, a pediatrician at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., who told Morning Edition these tips: “Taking lots of breaks, especially if they’re being physically active, drinking a lot of water, also using sun protection” such as sunscreen and a hat.

Heat domes affect different parts of U.S.

Heat domes have struck other regions in recent years. In early June of last year, the Western U.S. suffered high temperatures that were 20 to 30 degrees hotter than normal. In 2023, a dome that formed over a huge swath of the Great Plains, South, and Midwest in late August brought a rash of record temperatures from New Orleans to Chicago. For the second year in a row, there were more than 600 heat-related deaths in Arizona’s Maricopa County in 2024 and Phoenix saw a record 113 consecutive days of temperatures at or above 100 degrees.

And in 2021, a heat dome broiled Oregon, Washington and other parts of the Northwest in the early summer, causing hundreds of deaths.

Last month, virtually every part of the world was affected by widespread warming.

“May 2025 was the second warmest May on record,” according to the National Integrated Heat Health Information System. “Temperatures … were much warmer than average across parts of every continent.”

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

FBI release photos and video of potential suspect in Guthrie disappearance

An armed, masked subject was caught on Nancy Guthrie's front doorbell camera one the morning she disappeared.

Reporter’s notebook: A Dutch speedskater and a U.S. influencer walk into a bar …

NPR's Rachel Treisman took a pause from watching figure skaters break records to see speed skaters break records. Plus, the surreal experience of watching backflip artist Ilia Malinin.

In Beirut, Lebanon’s cats of war find peace on university campus

The American University of Beirut has long been a haven for cats abandoned in times if war or crisis, but in recent years the feline population has grown dramatically.

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

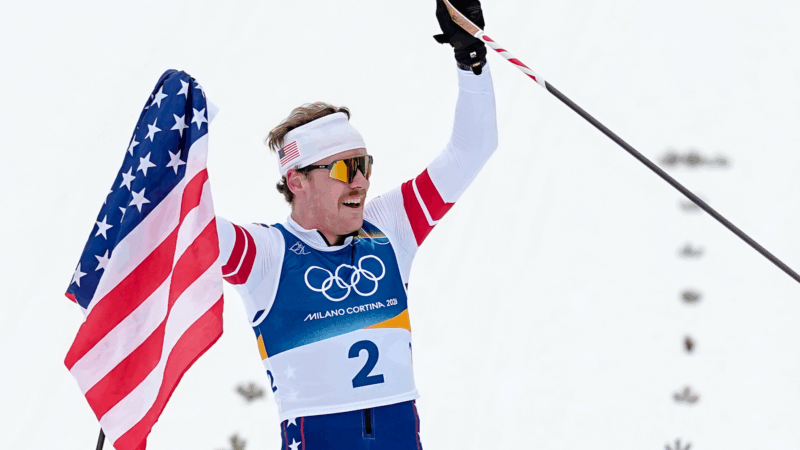

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.