A ‘college for all’ push thrived in New Orleans after Katrina. It wasn’t for everyone

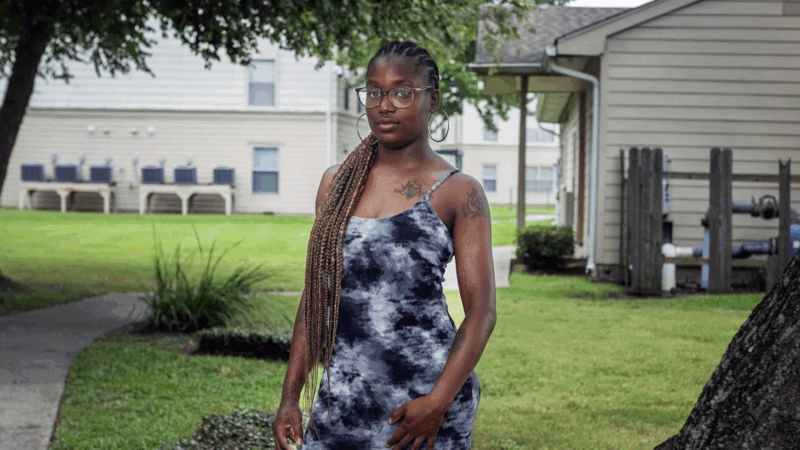

All through middle and high school in New Orleans, Geraldlynn Stewart heard the message every day: College was the key to a successful future. It was there on the banners that coated the doors and hallways, advertising far-flung schools, like Princeton University and Grinnell College. And she could hear it in the chants students recited over and over again. This is the way! We start the day! We get the knowledge to go to college!

Yet even after enrolling in 2014 at Dillard University, a private historically black college in the heart of New Orleans, Stewart never felt at ease in that prescribed path.

Like most of her classmates, Stewart came from a working class family. She didn’t have close relatives who had graduated from college. Even with her tuition covered by a state scholarship, and a small loan, it was an ongoing challenge to pay for books, gas, a lab coat for biology class, food and many other expenses. The then-18-year-old didn’t want to be a financial burden on her mother, who had multiple jobs in the French Quarter.

”My mom was a nonstop worker,” Stewart says, “she does that still to this day.”

So on top of her classes, Stewart had a nearly full time job at Waffle House.

But by her second semester at Dillard, the job had eclipsed school, and Stewart decided that she had to choose one or the other. She chose the job — a decision with financial and career implications that would ripple throughout the next decade.

“I gave up on myself,” she says now.

Having some college experience but no degree is a common narrative among New Orleanians around Stewart’s age. After Hurricane Katrina devastated the city 20 years ago, schoolchildren returned to a flurry of new charter schools opening up, many of them united in a mission that was starting to crest across the country: college for all.

It was a founding ambition of the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP) national charter school network, which Stewart attended in New Orleans starting in 2006, when she was 10 years old.

“That was our most singular focus for those beginning years,” says Rhonda Kalifey-Aluise, the longtime CEO of KIPP New Orleans Schools.

The broader idea at the time was this: Schools that kept a relentless eye on sending more students to and through college could help lift the next generation of New Orleanians out of poverty.

But 20 years on, the legacy of that college push in the lives of Stewart and her peers is complicated.

Stewart, her sister and her stepsister all bought into the messaging, and gave college a try.

Each sister would, like Stewart, face immense obstacles in college from day one.

“It was not a straight path at all,” says Stewart’s stepsister, Mary Dillon, who also attended a KIPP school. “ My journey through college was super hard…It was a lot of trials and tribulations, ups and downs.”

Their stories offer a microcosm of the challenges so many New Orleans students experience after high school – and they show the importance of understanding a community, and its needs and aspirations, when pushing students toward higher education.

More students are going to college. But many don’t stay

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans schools received an infusion of disaster recovery funds, and charter schools replaced traditional public schools in a way that had never been seen before. Those changes made a big difference in a system that serves mostly Black, lower-income students.

Before the storm, test scores in New Orleans were among the lowest in Louisiana, and in 2005 only 56% of students graduated from high school on time. The year before Katrina, just over a third of high school graduates enrolled in college. In the decade after Katrina, test scores, graduation rates and college enrollment rates all went up.

But those improvements haven’t extended in the same way to college graduation rates.

While a 2018 study found more students stayed in college compared to before the flood, a follow up in 2020 – that included students from Stewart’s era, who had spent much more time in post-Katrina schools – reported no significant change:

Before Katrina, about 1 in 6 New Orleans students didn’t make it past their first semester of college. More than a decade later, in 2016, that figure had barely changed.

“You do end up with a lot of students going to college and not finishing,” says Doug Harris, director of the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University, and a co-author of both reports.

In a school system that serves so many lower-income students, even the most academically prepared may quickly find themselves overwhelmed by personal and financial strains that their more affluent peers rarely encounter at college. Harris points out that lower-income students, in both Louisiana and nationally, have lower college completion rates on average.

“Twenty years post-Katrina, that is something that I’m still struck by, that education can’t solve for poverty in and of itself, ” says Vincent Rossmeier, who studies the city’s education system at Tulane’s Cowen Institute.

College dreams, and some naivete

Stewart’s introduction to KIPP came one summer evening in 2006, when a teacher at the brand new KIPP Believe College Prep stopped by her family’s home in the 7th Ward. The teacher hoped to recruit fifth graders, and Stewart’s mother liked what she heard. There would be strict rules, long school days, and a relentless focus on learning.

At that time, the city’s public school system was in the midst of a dramatic reconstitution: The predominantly Black teacher corps had lost their jobs, and new charter schools were opening up, often hiring young, white teachers and leaders from out of town. Those teachers, many of them recruited through Teach for America, were often devoted ambassadors for the college enrollment push, which had traction well beyond New Orleans.

In his first address to Congress in 2009, President Barack Obama asked every American to pursue some form of education beyond high school. “Whatever the training may be, every American will need to get more than a high school diploma,” he said.

For her part, Stewart felt ambivalent about higher education. Styling hair was a longtime passion, and she sometimes wondered if there was a way to pursue cosmetology.

But, she says, “ KIPP really made it a point—that’s what we want: college, college, college.”

(Nikki Kahn | The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Overall, she mostly enjoyed KIPP. And when middle school ended, her mother enrolled her at a KIPP high school — the first in New Orleans to open. (If KIPP ever started a college, Stewart joked that her mother would be first in line to sign her up.)

As a freshman in 2010, there were thermometer-shaped posters lining the hallways showing which families had started saving money for college. And the school’s principal regularly recited the mantra, “One thousand first generation college graduates by 2022.”

Stevona Elem-Rogers is a leader at Black Education for New Orleans, which supports Black educators and schools in the city. She says, in schools like Stewart’s, there was some naivete – especially among the mostly young, white teachers and leaders – about the particular challenges Black, first-generation students encounter at college. Vital questions and concerns could go unaddressed.

“You’re going to hype me up and tell me, ‘Go to college.’ What’s my money plan?” Elem-Rogers says. “What’s my full, thought-out plan for how I enter into this space? What am I majoring in? Have you helped me think through the nuances of that?”

Their college journeys weren’t easy

In 2014, Stewart arrived at her first English class at Dillard University wearing her Waffle House uniform – she didn’t have time to change. From the start, she juggled a full class load with a 30- to 35-hour work week.

“It started overpowering my going to school,” she says.

She started Dillard with a large group of classmates from KIPP. One of those classmates, Khalil Pollard, says they all struggled with financial concerns and family obligations.

“We were all dealing with family and personal issues, financial issues, and just trying to make it,” he says. “Being in school [we] were very broke, hungry, and didn’t have that many resources.”

Pollard took several Advanced Placement courses at his KIPP high school, so he was able to skip some classes at Dillard — a big boon, he says. But the intense regimentation and handholding at KIPP didn’t always help in terms of preparing students for the independence of college, Pollard adds. At Dillard, skills such as self-advocacy and time management were so important, and he often felt at a loss. “Once we got to college, you realize, damn, we weren’t prepared for this.”

Pollard had to take his younger sister to classes with him most days freshman year, and it consistently made him late. That was a major factor in his failing a class, he says, and losing crucial scholarship funds. If his mother hadn’t been able to take out a loan to help, Pollard says he would have dropped out.

One by one, he watched as his former KIPP classmates, including Stewart, did just that. He recalls that when he finally walked across the stage in 2018—right on time, against all odds—there was only one other student from his KIPP high school still with him.

“I had to fight and push through,” he says.

Stewart’s two sisters have similar stories of struggle.

Jasmine Stewart, Geraldlynn’s older sister, was the first in her family to enroll in college, at Southern University at New Orleans (SUNO), a public HBCU. She did not attend a KIPP school like her sister, but her high school also encouraged college, and she says her parents were influenced by the messaging that was pervasive in the city at the time.

Jasmine met her future husband at SUNO, but after three semesters of struggling with grades, and too little academic counseling and support, she decided to leave.

“At some point I felt like I was there because everybody else wanted me there,” she says.

Mary Dillon, their stepsister, was the youngest; she attended the same KIPP middle school that Geraldlynn did, and also enrolled at Dillard. Nothing was easy about her time there.

She had a baby in high school, who often had to accompany her to college classes. She says things were already tough when her uncle was shot and killed, making it impossible for her to focus on school.

“I flunked every class that semester and literally was about to quit,” she recalls.

Dillon credits mentors and teachers from her KIPP middle school for supporting her. “My journey through college was super hard and honestly, KIPP was right there every step of the way,” she says, adding that one advisor even flew in from out of state in a particularly rough moment to offer counsel.

With the help of some summer classes, Dillon graduated on time in 2019—a feat she had doubted would be possible many times over the years.

“It was a lot of hurdles: jumping, tripping, falling,” she says. “But I made it. I definitely made it.”

Where the sisters are now

The sisters are now in their late 20s and early 30s, and KIPP remains an integral part their lives: Five of their children now attend KIPP Believe, which has a middle school that two of the sisters attended. And Jasmine Stewart and Mary Dillon both work at KIPP Believe, as a paraprofessional and a teacher, respectively.

Jasmine says she loves her work, but she wants to lead her own classroom someday—something she can’t do without a college degree. So, at age 31, she’s back at SUNO, this time taking classes online. With a full-time job and two kids, she tries to cram all of her schoolwork into the weekend.

“I’ve been staying afloat,” she says, but “I can’t give it my all…I have to give it the best I can.” Jasmine adds that, “ It will be so worth it in the end.”

Dillon has taught third grade English at KIPP Believe’s elementary school for the past few years. She continues to push her family to get the education and training they need to pursue their dreams.

“We are going to get hurdles,” she says. “We just have to figure out what truly makes us happy and run with it, regardless of what tries to get in the way.”

For Geraldlynn Stewart, there continue to be some obstacles. Now 29, she lives with her partner and three kids in New Orleans East. She’s helped support her family through jobs at the airport, Walmart and now Target. But she has bigger career ambitions.

“Financially, I’m not where I want to be, and it bothers me because I know I could have been in a different situation,” she says.

Earlier this year, Stewart had the opportunity to pursue a long-time dream: enrolling in a cosmetology program. She passed the admissions test and took the required tour. But there was one obstacle in her way: A $1,200 balance on a loan from her time at Dillard lingers. (She says, at one point, she had paid back the entire loan, but it was refunded during the pandemic and she spent the money, not realizing that it could come due again.) She can’t get financial support to attend this cosmetology program until that balance is cleared.

“My having that open loan is hindering me from even starting my career path,” she says.

“Now my struggle is being [29] with three kids,” she adds, “and not knowing what’s my purpose.”

“All students should have the opportunity to go to college, if they want to”

Today, surveys show many Americans are questioning the value of a college degree.

And despite years of many New Orleans high schools pushing for students to pursue higher education, a 2024 poll from the Cowen Institute found only 32% of New Orleans parents and guardians said their child planned to attend a four-year college. That number shrank even more for Black parents, to 23%, and for families that earn less than $40,000, it shrank to 13%. Lower-income parents were also the most likely to support increased career and trades training in the high schools.

KIPP leaders say they’re trying to change to better reflect their community. As at some other charters, there’s more of a priority on hiring teachers who come from similar backgrounds to the students.

And there’s more of an emphasis on local traditions. In the spring, a classroom at KIPP Believe had a banner on the door advertising the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club — a historic, mostly Black Mardi Gras organization — not a college.

College persistence remains a struggle for KIPP’s New Orleans graduates, with the pandemic aggravating longstanding challenges for everyone, according to Kalifey-Aluise, KIPP New Orleans Schools’ CEO. But the charter network wasn’t able to provide college completion numbers for its graduates in New Orleans.

Over the years, KIPP has also mellowed when it comes to college for all. Kalifey-Aluise says the group remains committed to the idea that college is the surest path out of poverty. “We absolutely believe that all students should have the opportunity to go to college, if they want to.”

But college no longer looms so large. In recent years, KIPP’s high schools have prioritized individual college and career counseling; and they have also offered some access to technical fields, like Geraldlynn Stewart’s long-time passion, cosmetology.

“I think sometimes the perception is KIPP started as ‘college only’ and now we’re career and we’ve sort of abandoned one for the other,” says Kalifey-Aluise, adding that it’s really about both.

“If we do it well, students will be able to make whatever choice, right?” she says. “It’s whatever they want, not which one we want.”

For those who are college bound, the organization also tries to do a better job matching students to institutions where they will be more likely to thrive, says Korbin Johnson, a longtime principal for KIPP New Orleans.

“It’s not just, ‘Hey, what’s the top college you think you can get into? You gotta go there,'” he says.

Now, Johnson says, there’s often a deeper conversation. “Where do we think you’ll be most successful? And tell me what’s important to you? What do you want to study? How far away from home do you want to be?”

Geraldlynn Stewart feels as if she might have benefited from some of the changes at KIPP, especially the broader view of potential career paths.

“I wish they drilled what they’re doing now to those kids into us because I feel like we probably would have been better off,” she says.

Stewart’s oldest child, 8-year-old Harmony, says she has many career aspirations, including being a teacher or a doctor.

“My mom wants me to be an artist because I know how to draw very well,” Harmony says.

But in the end, Stewart cares most of all that her deeply creative daughter has the opportunity to experience “every little thing she possibly can.”

Whether college or not, she wants Harmony’s decisions and destiny to be entirely in her own hands.

Sarah Carr is the author of Hope Against Hope, which follows a principal, a teacher and a student — Geraldlynn Stewart — as they navigate New Orleans schools after Hurricane Katrina.

Reporting contributed by: Aubri Juhasz

Edited by: Nicole Cohen

Audio story produced by: Lauren Migaki

Transcript:

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Twenty years ago, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, and in the wake of the storm, charter schools replaced traditional public schools in a way that had not been seen before. Many of those charter schools promoted the idea that every student should go to college. Now at a time when polls show many Americans question the value of a college degree, reporter Sarah Carr looks back at the successes and failures of the college for all movement.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED CHILDREN: (Chanting) KIPP.

SARAH CARR: There was one charter school operator after Katrina that epitomized the college for all push in New Orleans. They even had an anthem for it.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED CHILDREN: (Chanting) Got to read, baby, read. Got to read, baby, read, and go to college.

CARR: KIPP, which stands for the Knowledge is Power Program, is a national charter school network. In New Orleans, it served mostly low-income Black students, and it kept a relentless eye on the same prize – college.

GERALDLYNN STEWART: (Chanting) Read, baby, read. You got to read, baby, read.

CARR: Geraldlynn Stewart was 9 years old when Katrina hit. Afterwards, she ended up at KIPP schools.

STEWART: KIPP really made it a point to like, college, college, college, college. That’s what we want. We want college, college, college, college, college.

CARR: And in 2014, she went, but she left partway through her second semester, far from a degree.

STEWART: Financially, I’m not where I want to be. And it bothers me because I know I could have been somewhere, you know, in a different situation.

CARR: She recently tried to enroll in a cosmetology program, a long-time dream, but there was something holding her back – a decade-old student loan. A $1,200 balance lingers. She supported her kids through jobs at the airport, Walmart and now Target. But as hard as she works, clearing the balance hasn’t been easy.

STEWART: Now my struggle is being 28 with three kids and not knowing what’s my purpose.

CARR: Today, the earliest graduates of those college-focused high schools are in their late 20s or early 30s, and there’s some solid data on how things went for them after charters came to town.

DOUG HARRIS: Test scores, high school graduation rates, college-going, everything improved, and everything improved a lot.

CARR: Education researcher Doug Harris says more students started college.

HARRIS: We’re almost at the top of the state at this point in college-going rates, which is remarkable.

CARR: The problem is many students didn’t stay in college. Harris, who works at Tulane University, looked at college persistence at the time Geraldlynn Stewart’s cohort would have been enrolled. In a study, his team found that before Katrina, about 1 in 6 New Orleans students didn’t make it past their first semester. And more than a decade later, in 2016, that figure had barely changed.

VINCENT ROSSMEIER: That’s something that really needs to be focused in on is what is happening once students actually get to college that’s preventing them from graduating.

CARR: Vincent Rossmeier also studies New Orleans schools at Tulane. In a school system that’s mostly Black and lower income, he says, students can find themselves overwhelmed at college by personal and financial strains their more affluent peers rarely encounter.

ROSSMEIER: Twenty years post-Katrina, that is something that I’m still struck by that, you know, education can’t solve for poverty in and of itself.

CARR: But back in the 2000s when Geraldlynn Stewart started attending KIPP schools, there was a lot of optimism and some naivete that those challenges could be overcome, that there was no need for a plan B. At the time, Stewart felt pretty ambivalent about college. But eventually, she says she bought into KIPP’s messaging.

STEWART: It’s what we want, as us kids, wanted to hear.

CARR: After she graduated from high school in 2014, Stewart enrolled at Dillard University, a private, historically Black college in the heart of New Orleans. She juggled school with a nearly full-time job at Waffle House.

STEWART: I was so much focused on financially being able to stay at this college because Dillard isn’t a cheap school.

CARR: Stewart didn’t want to be a financial burden on her mother. She had a scholarship and a small loan, but it remained a hustle.

STEWART: I had to buy a lab coat for biology class, and I had to have money for food to eat because you got to eat.

CARR: She hit a breaking point during her second semester and withdrew from Dillard to focus on earning money.

STEWART: I gave up on myself, pretty much. I really did. I gave up on myself.

CARR: Other classmates from KIPP also enrolled with Stewart at Dillard and struggled with money and family obligations. One of her classmates told NPR he remembers starting with a big group of KIPP alums, but over the years, most withdrew. Things would get a little better for KIPP graduates at Dillard over the next couple of years. The charter network wasn’t able to provide college completion numbers for its graduates in New Orleans, but it acknowledges that setting students up to finish college remains a big challenge.

RHONDA KALIFEY-ALUISE: Persistence is the struggle.

CARR: KIPP New Orleans CEO, Rhonda Kalifey-Aluise, says KIPP remains committed to the idea that college is the surest path out of poverty. But the organization has mellowed when it comes to college for all.

KALIFEY-ALUISE: We absolutely believe that all students should have the opportunity to go to college if they want to.

CARR: If they want to. Their high schools have prioritized individual college and career counseling, and they’ve started to offer a little more access to technical fields like cosmetology.

KALIFEY-ALUISE: It really is a both/and.

CARR: Geraldlynn Stewart’s family has remained loyal to KIPP, and for the most part, Stewart says she likes the way the organization is changing.

HARMONY: One, two, three…

HARMONY AND HARLEM: …All eyes on me.

HARLEM: One…

HARMONY AND HARLEM: …Two, eyes on you.

CARR: Twenty years after Katrina, her oldest kids are KIPP students themselves.

HARMONY: My name is Harmony.

HARLEM: And Harlem.

CARR: This year, Harmony is starting third grade. Harlem is in first. At school, their mother says they’re exposed to all kinds of trades and occupations, from doctors to firefighters.

STEWART: I wish they drilled what they’re doing now to those kids and to us because I feel like we probably would have been better off.

CARR: Harmony has many career aspirations.

HARMONY: I might be a teacher or doctor, but my mom wants me to be artist because I know how to draw very well.

STEWART: I want her to experience every little thing she possibly can. Like, she’s very – like, she’s just – she’s amazing.

CARR: But what’s most important to Stewart is that her daughter has opportunities of all kinds, college or not, and never feels trapped by someone else’s vision of who she should be in this world.

For NPR News, I’m Sarah Carr in New Orleans.

SIMON: And WWNO reporter Aubri Juhasz also contributed to this story.

(SOUNDBITE OF STREAMBEATS BY HARRIS HELLER’S “SAN ANDREAS”)

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."

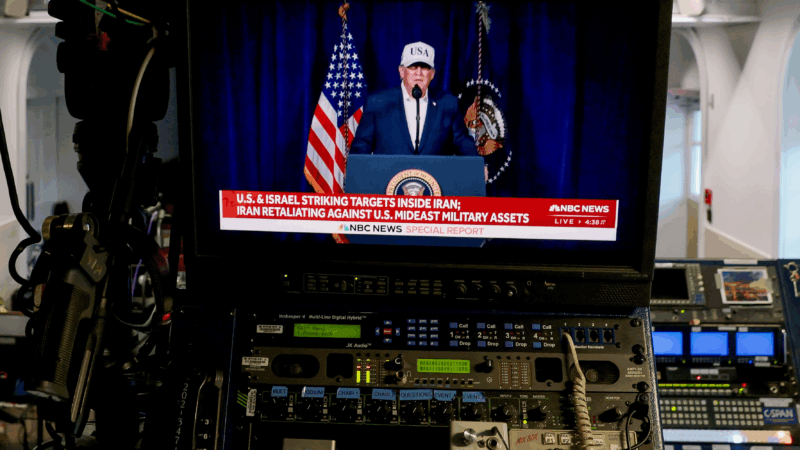

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.