4 essential conversations every interracial couple should have

When I married my wife, Jennie, we were in love with little concern about how our racial differences would affect our relationship. But I hadn’t anticipated the work it would take to be in an interracial couple.

I’m Black, white and Jewish, and Jennie is Italian and Irish. Over our more than 10 years together, we’ve had tough discussions about being Black and white, how to raise our two multiracial children, and how to cope with biases among ourselves, our families and our community.

These challenges have made us stronger. But it took us many years to learn how to talk about them in a constructive way.

Whether you’ve just started dating someone outside your race or have been in an interracial relationship for years, I’ve gathered advice from experts on how to deal with conflict and cultural misunderstandings, and make a new family culture at home.

With love and intention, interracial couples can thrive. But the journey will need to start with curiosity, says Nina Sharma, author of The Way You Make Me Feel: Love in Black and Brown. That means “being open to talking about one another’s cultures, both sharing and asking.”

Here are four essential conversations to help you manage some of the toughest parts of being in an interracial relationship.

Conversation No. 1: What are our differences?

For some couples, it might feel awkward to talk about each other’s racial and cultural differences. But don’t ignore them, says Kaoru Oguro, a psychotherapist and licensed clinical social worker who specializes in working with interracial couples.

They’re an important part of understanding “how race and power dynamics affect the relationship,” she says.

For new couples, the conversation can sound like: Teach me about your language. Have you ever felt othered by your skin color? How would you describe your hair?

If you do not discuss these differences early in the relationship, they may present themselves later in ways of conflict. For example: What is your family saying about me in their language? Why do you think you’re going to get pulled over by the police? Do you really need to get your hair done every week?

Longtime couples might ask: What are your religious or spiritual beliefs? What biases or stereotypes do you carry? What family traditions do you want to keep? These questions can help you make decisions about your future together.

Conversation No. 2: How do we make our own family culture?

After naming your differences, talk about each other’s culture and decide which parts you want to celebrate. Oguru says this exercise is not about having one culture prevail. It’s about “blending and co-creating” with your partner in ways that help you feel both understood and respected.

To me, co-creating is one of the greatest joys of interracial relationships. Jennie and I bring our differences together by exposing our children to their mixed background. We read them books about Black history icons like NASA astronaut Mae C. Jemison. They eat Mommom’s homemade Italian dinner on Sundays. And we send them to a Jewish summer camp to learn about their heritage.

If you need some inspiration, try this thought experiment that I put together for my own family: What might your new culture look and feel like to the senses?

Maybe it sounds like both Puerto Rican music and Indian music playing at a family party. Maybe it smells and tastes like the tang of kimchi and the zest of cilantro-lime tacos. Maybe it feels like the smoothness of cocoa butter and the roughness of a woven mat.

These elements can give your blended cultures a tangible texture and flavor that feels unique to your family.

Conversation No. 3: How do we compromise about culture?

Sometimes, you’ll have different cultural or spiritual practices and will need to decide what that means for the family you’ve created together.

For instance, if your partner avoids meat on Fridays during Lent, do they expect you to do the same? Are you willing to? If you have kids, will your partner want them to avoid meat as well? How do you feel about that?

If you can’t agree on a solution, aim to negotiate, says Kwame Christian, founder and CEO of the American Negotiation Institute. Be curious and ask questions.

The conversation can sound like this: I understand we have this difference. I recognize it makes you feel this way. I hear you and I want us to figure this out together.

You don’t want one partner to have to abandon their culture just because they married someone outside of it. Rather, work together. “It is you and me versus the problem, not me versus you,” Christian says.

Conversation No. 4 How will we support each other in family and community spaces?

Even if a family member, friend or neighbor doesn’t oppose your relationship, they may still have biases about your partner’s race, ethnicity or religion.

Let’s say you and your Vietnamese partner are at a family barbecue. Your uncle, who is a Vietnam War veteran, makes a racist comment about Vietnamese people. How do you show your partner you have their back?

If you know these tensions are likely to happen, make a plan ahead of time, Christian says. Talk to your partner about what they need. Maybe they don’t want you to speak up. Maybe they’d like you to pull your uncle aside privately to say, “that’s not OK.” Or maybe they just want permission to skip the family barbecues altogether.

Whatever you decide, the idea is to have a united front with your partner in these moments. That is something you will need to continue working on throughout your relationship, says Sharma.

As an Indian woman married to a Black man, Sharma says she thought she and her husband were “out of the woods with the racism and anti-Blackness we’d experienced in our early years of marriage.”

But over time, she’s learned that some of those societal pressures still exist. So she and her husband practice what they call “Afro-Asian solidarity.”

“It’s something alive that you continue to unpack and grow,” she says. It communicates to your partner: “We’re on this journey together, doing that work.”

Davon Loeb is a husband, father and the author of The In-Betweens: a Lyrical Memoir, and his work has been published in The Washington Post, Parents, Los Angeles Times, Men’s Health Magazine, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Best American Essays and elsewhere.

This story was edited by Malaka Gharib. The visual editor is Beck Harlan. We’d love to hear from you. Leave us a voicemail at 202-216-9823, or email us at [email protected].

Listen to Life Kit on Apple Podcasts and Spotify, and sign up for our newsletter. Follow us on Instagram: @nprlifekit.

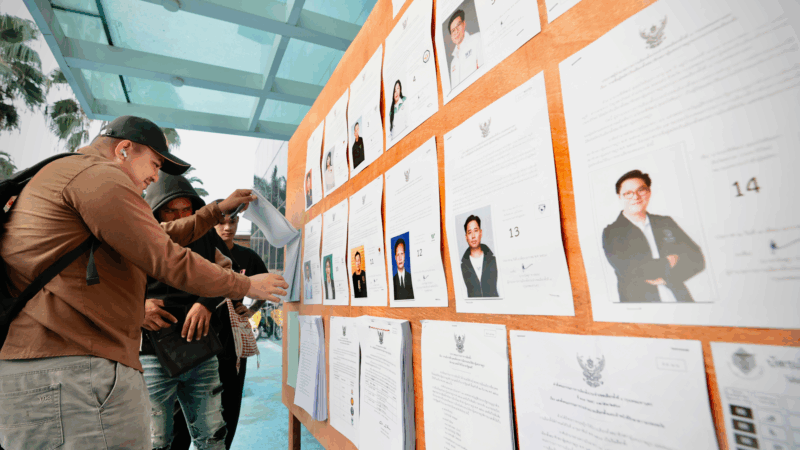

Thailand counts votes in early election with 3 main parties vying for power

Vote counting was underway in Thailand's early general election on Sunday, seen as a three-way race among competing visions of progressive, populist and old-fashioned patronage politics.

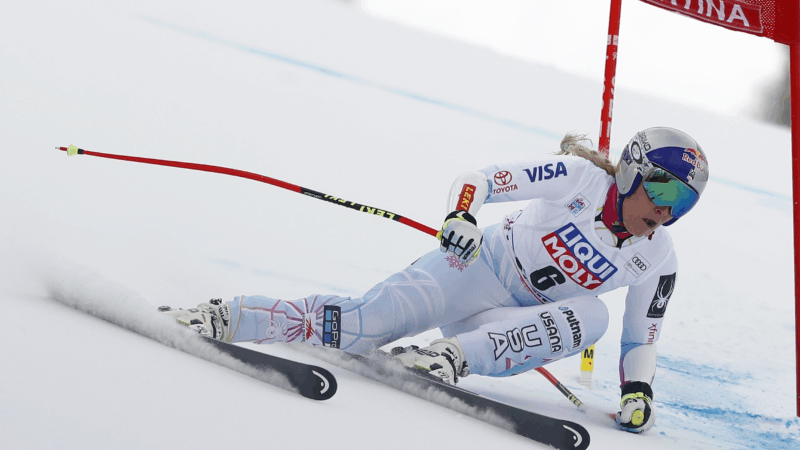

US ski star Lindsey Vonn crashes in Olympic downhill race

In an explosive crash near the top of the downhill course in Cortina, Vonn landed a jump perpendicular to the slope and tumbled to a stop shortly below.

For many U.S. Olympic athletes, Italy feels like home turf

Many spent their careers training on the mountains they'll be competing on at the Winter Games. Lindsey Vonn wanted to stage a comeback on these slopes and Jessie Diggins won her first World Cup there.

Immigrant whose skull was broken in 8 places during ICE arrest says beating was unprovoked

Alberto Castañeda Mondragón was hospitalized with eight skull fractures and five life-threatening brain hemorrhages. Officers claimed he ran into a wall, but medical staff doubted that account.

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.