20 years ago, New Orleans fired its teachers. It’s been rebuilding ever since

Even when she was a little kid growing up in New Orleans, Stacey Gilbert knew she wanted to be a special education teacher.

She remembers her reaction to the 1962 film The Miracle Worker, about Helen Keller, and watching other movies about children with special needs.

“I would say, ‘That’s the type of children I wanna teach.'”

In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit her hometown, Gilbert had been teaching in the city’s public schools for almost two decades.

“I can still remember that particular Friday, and just thinking, ‘OK, we’re gonna evacuate, but we’ll be back.'”

But Gilbert didn’t come back for months – and when she did, she no longer had a job waiting for her.

After Katrina flooded much of New Orleans, public education in the city came to a complete stop. As schools reopened – many as charter schools – most of the city’s educators didn’t get their jobs back. Instead, they were often replaced with young people who were both new to town and to teaching.

People in New Orleans have strong opinions about whether the changes to the city’s schools have been good or bad.

“The people that did come down, they were well-meaning, but they weren’t trained,” says Renee Akbar, a professor of educational leadership at Xavier University of Louisiana, one of the city’s HBCUs.

The data, though, is hard to argue with: Test scores, graduation rates and college-going all improved, and are still holding steady.

Still, the changes to the teacher workforce were painful for many veteran educators.

Before the storm, the majority of New Orleans educators were Black women, like Gilbert, who were certified to teach, and the average teacher had about 15 years of experience.

Over the next few years, the percentage of white teachers grew quickly, from around 25% in 2005 to over 40% by 2011. By that same year, half of all New Orleans teachers had been on the job less than 5 years. It would be years before those numbers got closer to where they were before the storm.

How Teach for America grew in New Orleans

Many of the new teachers came to New Orleans through Teach For America, or TFA, a national program that places mostly recent college grads in public schools for two years.

From 1990 to 2005, TFA placed an average of 50 corps members a year in New Orleans and other nearby parishes, according to the region’s executive director, Ge’ron Tatum. After the storm, that number more than tripled.

Lauren Jewett was a senior at the University of Rochester in New York when she applied for TFA in 2008.

Jewett says she had been thinking about going to law school, but wanted to get work experience and found the organization’s pitch appealing.

“The mission of the program – and I believe it’s still the case – is that the program aims to address educational inequities.”

After what Jewett describes as a “rigorous” application process, in which she volunteered to teach special education, she was accepted and placed in TFA’s Greater New Orleans corps.

Unlike Stacey Gilbert, Jewett hadn’t gone to college to be a teacher and wasn’t certified to teach, which was typical for TFA.

The program began with a six-week crash course in Phoenix, she says, where she taught summer school while she learned how to teach.

Jewett remembers attending sessions where she was asked to think about her identity and how to be “sensitive” when working with different communities.

“I have since gone through many other trainings that have been much more robust,” she says. “I just think that there was a lot missing.”

Looking back, Jewett says it was impossible to cram everything new teachers would need to know into such a short period of time.

That was more than 15 years ago.

Today, TFA says corps members receive online training before heading to their region for additional classes. And they teach summer school locally, rather than in a different city, like Jewett did.

In a statement, Tatum said, “All of our corps members receive rigorous training, ongoing coaching” to ensure that “they are prepared and supported to teach effectively while continuing to grow their practice.”

“People had this perception that we were bad teachers”

Renee Akbar says before the storm, New Orleans’ teachers were a big part of the city’s Black middle class. They had deep roots in their communities and long histories with families.

“They probably taught the aunties, the uncles – the grandma even, some of them,” she says. “That makes a world of difference when you want kids to be successful.”

Still, many New Orleans schools were struggling when Katrina hit. The district had been neglected and mismanaged for decades, stretching back to when white flight picked up in the 1970s, and later corruption – which eventually led to FBI investigations – made everything worse.

Only 56% of students graduated on time in 2005, and the district ranked second-lowest in the state based on test scores.

After the city flooded, no one knew when schools would reopen, and the district placed its 7,500 employees, including about 4,300 teachers, on unpaid leave. Soon after, state officials took over most of the city’s schools, and the school board laid everyone off.

Stacey Gilbert says because schools were low-performing before the storm, “people had this perception that we were bad teachers.”

But the real problem, she says, was poverty, and that schools didn’t have enough resources to pay for things like textbooks and even toilet paper.

“We were about students and teaching and getting the job done by any means necessary,” says Gilbert. If they needed something for their students, she says, teachers often had to buy it themselves. “That’s what we did.”

When veteran teachers like Gilbert came home after the storm and applied for jobs at the state-led schools, they were asked to take a proficiency exam. Some of the city’s charter schools made applicants take tests, too.

“That was really a slap in the face,” Gilbert recalls. “Like, ‘Wow, to get my job, you want me to take a test?’ “

Less than a third of the city’s pre-Katrina teachers returned to the system. Others got teaching jobs elsewhere in the state, like Gilbert, who got hired just outside New Orleans in Jefferson Parish.

Meanwhile, programs like TFA helped charters fill the gap and staff their schools with a new kind of teacher. Like Jewett, most were new to teaching. And only a quarter of her corps colleagues identified as people of color.

When it came to special education, Jewett had to teach herself

In 2011, after just two years of teaching special education, Jewett became the expert at a new charter school – a common story in a system full of newbies. She was responsible for coordinating academic, behavioral and other services for roughly 200 students in grades K-4.

“I had to find thought partners,” she says. “Meanwhile, it was like I was navigating people who didn’t know much, too, [who] were working in the school system – leaders.”

Jewett remembers state education officials visiting the school and looking at the behavior plans she’d written for her students. Those plans are legally required documents that schools are supposed to use to support students with special needs. A state official was impressed by what she saw.

Jewett says, “She asked me who taught me, and I told her, ‘I taught myself.’ “

Jewett says some of the practices that should have been in place to protect children with disabilities were missing at the school, and not all children got the services they needed.

She says she later learned the “dysfunction” at her school wasn’t isolated. In 2010, families filed a lawsuit alleging special education violations at some charter schools, including allegations that students were denied accommodations that they are legally entitled, denied admission to schools and in some cases pushed out of their school completely. A settlement in 2015 led to regular reports from an independent monitor – to this day, that monitor still flags possible violations of federal disability laws in New Orleans schools.

“I was really disgusted,” says Jewett. “It just didn’t seem in line with what we were fighting for.”

She thought about quitting her job and leaving teaching altogether. Then she connected with the city’s teachers union, she says, and gained a lifeline.

The teachers union connected new teachers with veterans

New Orleans’ teachers union, United Teachers of New Orleans, had been an exceptional force in the city – and region – before Katrina.

UTNO was the first teachers union in the Deep South to negotiate a collective bargaining agreement in 1974, but it lost its contract – and most of its power – when its members were laid off after the storm. Today, teachers at just five of the city’s more than 60 charter schools have recognized union chapters.

Even after the union lost its influence, Jewett says it continued to support teachers. They hosted special education training where she was able to connect with current and former teachers who had more experience. The union even organized racial healing circles to bring together pre- and post-storm educators.

It was from the union that Jewett says she learned what had happened to veteran teachers like Stacey Gilbert.

“They weren’t able to come back to the city that they knew, the schools that they knew,” says Jewett. “And then all these other teachers [came] in to fill roles, especially white teachers who didn’t understand the culture and didn’t grow up here.”

Jewett says the city’s veteran teachers helped her understand her part in the new school system – and ultimately helped her find her place.

Today, the teacher workforce looks more like it used to

By 2013, teacher turnover in New Orleans had doubled.

That wasn’t good for students — and Akbar, at Xavier University, says charter schools noticed.

“Not having certified teachers from the community was not necessarily the right way to go.”

She says many TFA recruits didn’t stick around past their two-year contracts, and schools started hiring veteran teachers again.

Fast forward to today, and New Orleans’ teaching force looks more like it used to. About 67% of K-8 teachers and 62% of high school teachers now identify as Black.

The region’s TFA corps is back to its pre-storm size and more than half of members now identify as people of color. Akbar says charter schools don’t rely on TFA as much as they used to. Instead, they’ve partnered with local universities, including hers, and other programs to hire certified teachers with ties to the city.

Returning to a more traditional teacher workforce hasn’t undone the city’s post-Katrina gains. Today, test scores are much higher than before the storm, closer to state averages, and around 80% of students graduate from high school on time.

Stacey Gilbert’s son, Ryan Gilbert, is part of the post-Katrina generation of teachers from New Orleans.

“I had four years of training before I even was able to take a test to get certified to step foot in front of children,” he says.

Ryan was planning to become a dentist when, in a philosophy class his sophomore year of college, he says he thought, “I don’t wanna drill teeth for the rest of my life.”

When he told his parents he was changing his major to education, “I think they were confused. It was the whole like, ‘Teachers don’t make any money.’ And then from my mom it was, ‘It’s not what it used to be.'”

Ryan is a high school science teacher in New Orleans at Warren Easton Charter High School and recently started his 11th year in the classroom. He’s been at Easton, a Black-led charter, his entire career.

His mom, now the principal of a school inside the city’s jail, says that with time, she came around.

“ I was really proud of him and realize now that is where he should be,” says Gilbert. “Because the same passion I have about teaching, that’s what he has.”

Teaching has become Lauren Jewett’s passion, too.

After 16 years, she’s still teaching special education, and she says New Orleans now feels like home.

“I think I also feel very rooted to this place because it’s also kinda where I grew up.”

She sees herself as a lifelong learner – when it comes to teaching, and when it comes to the legacy of Katrina.

“There’s always things to learn here,” she says.

Edited by: Nicole Cohen

Audio story produced by: Lauren Migaki

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

After Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans 20 years ago, public education in the city came to a complete stop, and when schools reopened, many of the city’s educators didn’t get their jobs back. Instead, they were replaced with young people who were new to teaching and new to New Orleans. Aubri Juhasz of member station WWNO spoke with two teachers on opposite sides of that divide.

AUBRI JUHASZ, BYLINE: Even when she was a little kid growing up in New Orleans, Stacy Gilbert (ph) knew she wanted to be a teacher.

STACY GILBERT: Movies, like, with the blind girl – I can’t remember the name of it.

JUHASZ: Oh, yeah.

S GILBERT: I can’t remember…

JUHASZ: Helen Keller or someone else?

S GILBERT: That was it.

JUHASZ: OK.

S GILBERT: Helen Keller – and other movies, I would see and say, that’s the type of children I want to teach.

JUHASZ: When Hurricane Katrina hit her hometown in 2005, Gilbert had been teaching special education for almost two decades.

S GILBERT: I can still remember that particular Friday and just thinking, OK, we’re going to evacuate, but we’ll be back.

JUHASZ: But Gilbert didn’t come back for months. And eventually, teaching positions like hers started being filled with a different kind of teacher.

LAUREN JEWETT: My mom was a little worried about the weather.

JUHASZ: Lauren Jewett had never been to New Orleans when she joined Teach for America, or TFA. The two-year program places people – mostly recent college grads – in public schools that need teachers. Jewett hadn’t gone to college to be a teacher, but that wasn’t unusual for TFA. The program began with a crash course, an attempt to cram much of what new teachers need to know into just a few weeks.

JEWETT: Sessions on, like, sensitivity around working with different communities – like, that’s lifelong work. And how do you fit that in a six-week boot camp that involves many other topics?

JUHASZ: Before the storm, the majority of New Orleans teachers resembled Stacy Gilbert. They were Black women who were certified to teach and, on average, had about 15 years of experience. But by the time Jewett arrived in 2009, the percentage of white teachers was growing quickly. Many were out-of-towners who were brand new to teaching.

RENEE AKBAR: The people that did come down – they were well-meaning, but they weren’t trained.

JUHASZ: Renee Akbar has trained teachers at Xavier University of Louisiana, one of the city’s HBCUs, for over 20 years. She says, before the storm, the city’s teachers had deep roots in their communities.

AKBAR: They probably taught the aunties, the uncles, the grandma even, some of them. That makes a world of difference when you want kids to be successful.

JUHASZ: For decades, New Orleans schools had been struggling. In 2005, the state graded most of them as failing. After Katrina, state officials took over many of the schools and turned them into charter schools. When veteran teachers like Stacy Gilbert applied for a job, they had to take a proficiency exam.

S GILBERT: That was really a slap in the face. Like, Wow. To get my job, you want me to take a test?

JUHASZ: Less than a third of pre-Katrina teachers returned to the system. Others, like Gilbert, got jobs teaching elsewhere in the state. Meanwhile, newer teachers like Jewett were taking on a lot of responsibility. After just two years of teaching special education, she became the expert on staff, a common story in a system full of newbies.

JEWETT: I had to teach myself. Like, there wasn’t a high level of years of experience, too, in our building.

JUHASZ: By 2013, the majority of New Orleans teachers had been on the job less than five years, and turnover had doubled. That wasn’t good for students. And Akbar, at Xavier University, says charter schools noticed.

AKBAR: Not having certified teachers from the community was not necessarily the right way to go.

JUHASZ: She says many TFA recruits didn’t stick around, and schools started hiring veteran teachers again. Fast forward to today, and New Orleans’ teaching force looks more like it used to.

AKBAR: And somehow or the other, it kind of balanced off.

JUHASZ: Akbar says charter schools now rely on partnerships with local universities, like hers, to hire certified teachers with ties to the city…

RYAN GILBERT: Hi.

JUHASZ: Ryan (ph)?

R GILBERT: Yeah, I’m Ryan.

JUHASZ: …Teachers like Stacy Gilbert’s son, Ryan Gilbert.

R GILBERT: When I told my parents that I was changing my major to education, I think they were confused.

JUHASZ: He’s a high school science teacher in New Orleans and recently started his 11th year in the classroom.

R GILBERT: It was the whole, like, teachers don’t make any money. And then from my mom, it was, it’s not what it used to be.

JUHASZ: But with time, his mom says she came around.

S GILBERT: I was really proud of him and realized now that is where he should be because the same passion I have about teaching – that’s what he has.

JUHASZ: Teaching has become Lauren Jewett’s passion, too. After 16 years, she says New Orleans is now her home.

JEWETT: I think I also feel very rooted to this place because it’s also where I kind of grew up.

JUHASZ: Today, there’s room for teachers like her, who came after Katrina and chose to stay, alongside people who have always called the city home. For NPR News, I’m Aubri Juhasz in New Orleans.

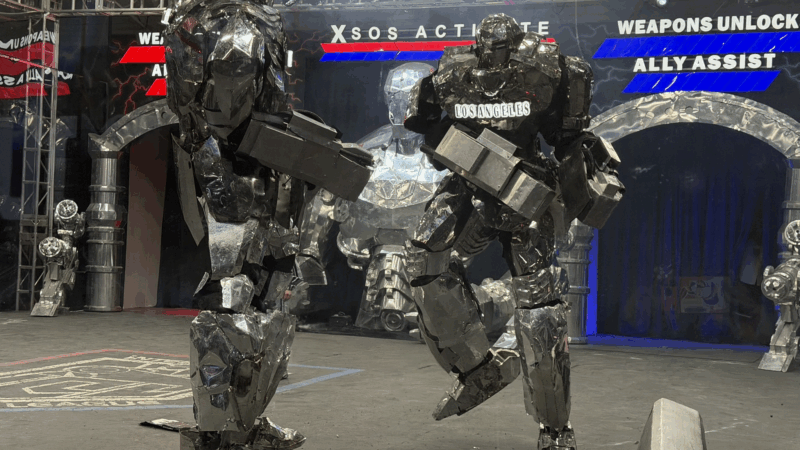

Giant robots battle it out in Detroit’s Robowar

Fighting robots is a cultural fantasy going back at least to Richard Matheson's 1956 story "Steel." One Detroit impresario is now bringing the idea to the stage — and real audiences.

Bill would move Alabama to closed primaries

Right now, any Alabama voter can participate in a primary election. Lawmakers in Montgomery took up a bill this week that would change that system.

Why ‘Sinners’ should win best picture (but probably won’t) — and more Oscar predictions

NPR critics share their hopes and predictions for the 2026 Academy Awards, which air on Sunday.

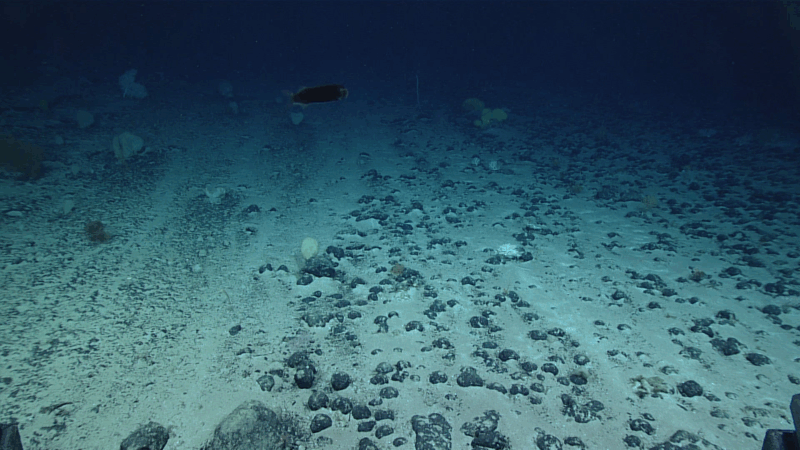

Countries are negotiating rules to mine the deep sea. The U.S. is pushing ahead alone

With growing interest in mining critical metals from the seafloor, countries are now negotiating international rules. The Trump administration is forging ahead on its own, speeding up environmental review for mining the fragile ecosystem.

4 confirmed dead after U.S. military aircraft goes down in Iraq

The U.S. Central Command confirmed that at least four of six crew members on the KC-135 aircraft were dead, after the refueling plane went down in western Iraq on Thursday.

It’s Chalamet vs. ballet in this week’s news quiz. Are your answers en pointe?

Meanwhile, if you've been paying attention to medicine, basketball and the British Parliament, you'll get at least three questions right this week.