100 years after evolution went on trial, the Scopes case still reverberates

One hundred years ago, the small town of Dayton, Tenn., became the unlikely stage for one of the most sensational trials in American history.

A local substitute teacher, John Scopes, was charged with the crime of teaching Charles Darwin‘s theory of evolution by natural selection.

At the time, it was illegal in Tennessee to “teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

The trial, which was orchestrated to be a media spectacle, foreshadowed the cultural divisions that continue today, and led to a backlash against proponents of evolution.

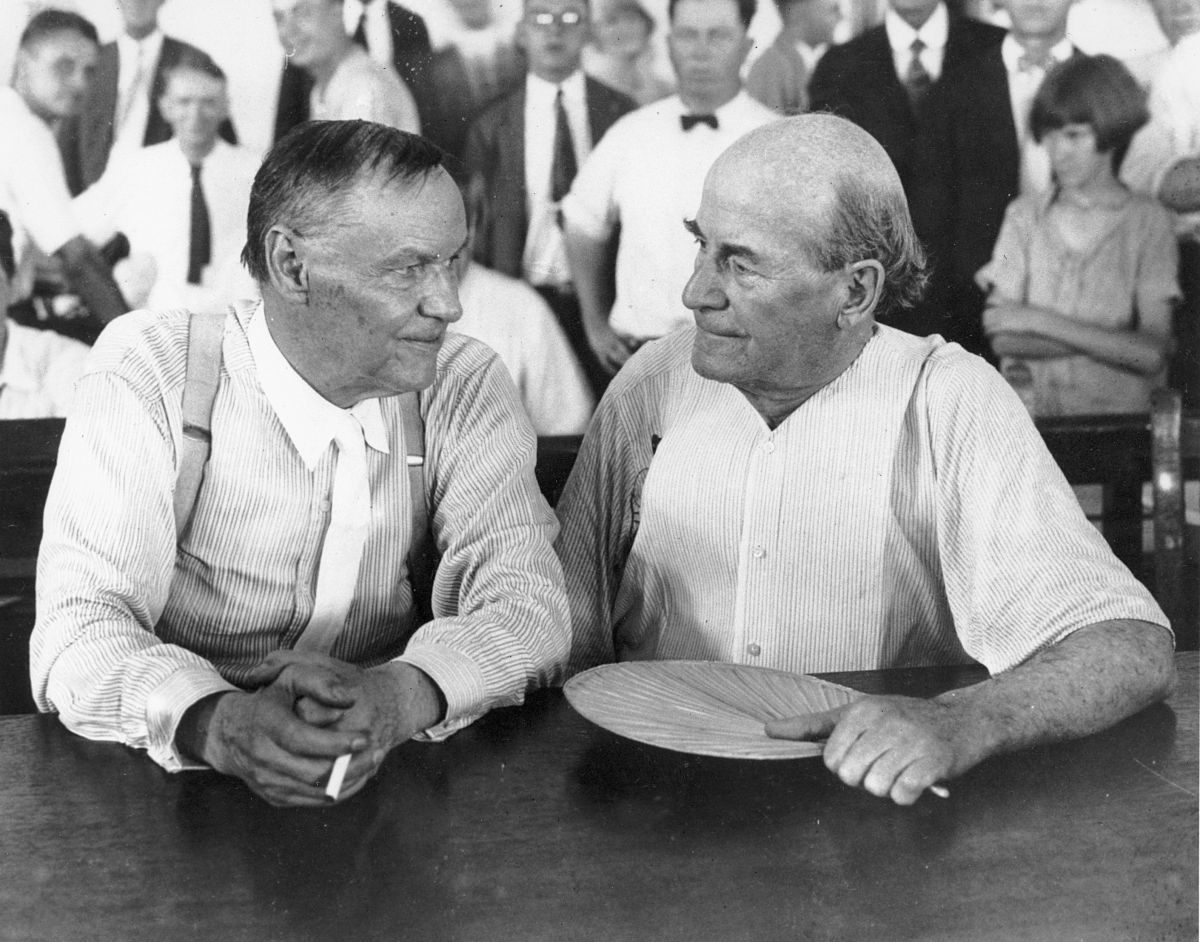

Clarence Darrow, a celebrated defense attorney, represented Scopes. Darrow was backed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in the organization’s first major case. William Jennings Bryan, a three-time presidential candidate, former secretary of state and staunch religious conservative, served as the prosecutor.

Covering the drama for The Baltimore Sun was the sharp-tongued journalist H.L. Mencken, whose national audience followed every turn of the case beginning with opening arguments on July 10, 1925.

Though the phrase “trial of the century” is often overused, the Scopes “Monkey Trial” — a name coined by Mencken — is arguably the original example, says Daniel Mach, director of the ACLU’s program on freedom of religion and belief. “It was being followed around the country. It was internationally famous,” he says, noting that this was the first trial ever broadcast on radio.

Although controversial, Darwin’s theory — first published in 1859 — steadily gained acceptance among scientists, even as it drew growing opposition from religious conservatives. By the 1920s, the rise of religious fundamentalism and Biblical literalism among evangelical Protestant groups was reshaping America’s religious landscape — setting it on a collision course with modern scientific thought.

That shift helped lead to Tennessee’s Butler Act, passed in 1925, which banned the teaching of evolution in the state’s public schools and universities.

The trial resembled a staged public debate, with Darrow and Bryan — two of the nation’s most renowned orators — volunteering to take part as the town sought publicity. Vendors sold refreshments while crowds gathered on the courthouse lawn.

Bryan “believed it was essential that humans were created in the image of God — and that’s where he staked his cross,” according to historian and author Edward Larson, a professor of history and law at Pepperdine University.

The spectacle of the trial is vividly captured in the 1960 film Inherit the Wind, a fictionalized retelling based on the play of the same name.

One thing that the film and play misrepresent is the circumstances of Scopes’ arrest, which was a deliberate test case to challenge the Tennessee law outlawing the teaching of evolution.

“It was a concocted trial,” says Larson. “Scopes never really taught evolution. … The town decided they wanted to stage this test of the new state law.”

In an unorthodox legal move at trial, Darrow — mirrored by Drummond in Inherit the Wind — famously called Bryan to the stand as a biblical authority. Although the judge in the case ordered Bryan’s testimony stricken, the decision to take the stand “played to Bryan’s vanity” and in the end, Bryan “got skewered,” Mach says.

But the outcome of the trial was never really in doubt. The jury deliberated for nine minutes before returning a guilty verdict. Scopes was fined $100.

Still, “some saw it as a moral victory for Scopes,” says Glenn Branch, deputy director of the National Center for Science Education (NCSE), a nonprofit dedicated to defending the teaching of evolution and climate change.

Newspapers around the country didn’t see the trial as decisive one way or the other, says Larson. Instead, their editorial pages mainly marveled at what appeared to be a huge rift in American culture: “Basically, they all said some version of, ‘Wow, this thing is huge. … This is a divide that is going to grow.'”

The Scopes trial marked one of the first highly publicized battles in the U.S. between traditionalist and modernist values surrounding science, religion and education — a conflict that continues to this day. The trial left a lasting impression on these debates, according to Adam Laats, a professor of education and history at the State University of New York at Binghamton.

“The Scopes trial didn’t start the 100-year culture war, but it made both sides realize how sharply divided we were,” he says. “These trench lines have stayed in roughly the same spot,” he says, “even though the issues have changed.”

Laats says the debate brought into focus by the Scopes trial still echoes in modern controversies — over abortion laws, posting the Ten Commandments in public schools, school-led prayer for student athletes, and whether parents have the right to excuse their children from classes that use LGBTQ+-themed storybooks.

Winning Scopes emboldened anti-evolutionists, leading to more court battles

Following the trial, several states in the South passed their own anti-evolution laws. In the coming decades, the teaching of evolution was absent or downplayed in much of the country.

Ken Miller, a professor emeritus of biology at Brown University, remembers his own science education in a New Jersey public high school in the 1960s.

“The textbook we used didn’t mention the word evolution,” Miller says. “Only in retrospect did I realize that that was sort of part of the aftermath of the Scopes trial.”

In the 1980s, religious fundamentalists pushed to have “creation science” taught alongside evolution in public schools. In notable court cases, a 1981 Arkansas law mandating this was struck down as a violation of church-state separation; the Supreme Court struck down a similar Louisiana law in 1987.

When Miller co-authored a high school textbook published in 1990, he wanted to emphasize evolution, which he calls the central idea in biology. At least one publisher’s marketing department, however, “asked us to de-emphasize the E word,” he says.

Instead, Miller’s textbook Biology, rich with references to evolution, was widely adopted in classrooms across all 50 states.

But in 2004, a Dover, Penn., school board member objected to the textbook and pushed to replace it with one that promotes intelligent design — the belief that certain features of life are best explained by an intelligent cause rather than natural selection. In the ensuing legal case, Kitzmiller v. Dover, a federal judge determined that intelligent design was “not a scientific theory.”

Casey Luskin, research director at the Discovery Institute, a think tank that promotes intelligent design, says the lasting impact of the Scopes trial “comes from the cultural retellings that we all watched in high school English class with Inherit the Wind.” He blames the movie for promoting “false and dangerous stereotypes” and says that’s led to censorship of scientists and academics who “challenge” evolutionary theory.

Many people now do not see their faith as being in conflict with evolution

Ken Ham, the founder and CEO of Answers in Genesis, which runs the Creation Museum and the Ark Encounter in Kentucky, says that in Scopes’ day, biology textbooks wrongly promoted arguments for evolution alongside eugenics and racist ideas, and that today’s science classes wrongly present evolution and shut out alternatives such as creationism.

“Darwinian evolution was just an attempt by Darwin to try to come up with a way of explaining or justifying naturalism,” Ham says, referring to the philosophical notion that shuns supernatural explanations for the world.

He sees the debate over creationism and evolution as the inevitable consequence of two fundamentally different worldviews.

“We always start from God’s word and build a worldview,” he says. “If you don’t start from God’s word, you start from man’s word. So really it comes down to there’s two foundations for worldviews, God’s and not-God’s.”

That said, he feels that belief in evolution over millions of years is compatible with being a Christian “because the Bible says it’s faith in Christ that saves you,” says Ham.

The National Association of Biology Teachers says that science educators should reject “calls to account for the history of life or describe the mechanisms of evolution by invoking any non-natural or supernatural notions, whether under the banner of ‘creation science,’ ‘scientific creationism,’ ‘intelligent design,’ or similar designations.”

Many people do not see their religious faith as being in conflict with evolution. Today, 80% of American adults believe that humans evolved over time, according to a Pew Research Center poll published in February, although a significant minority, 17%, believe humans have existed in their present form since the beginning of time.

Branch says the NCSE looked into why numbers have been trending in the direction of greater belief in evolution in recent years.

“One of the factors that seemed to have made a big difference was improvement in state science standards,” he says.

Specifically, a new framework of state science standards, which includes evolution, was introduced in 2013. Since then, they have been adopted by 20 states and the District of Columbia, Branch says, and have been influential all over the country.

Nonetheless, teachers can face pressures to downplay or de-emphasize evolution, says Miller.

He points out that last year, West Virginia passed an ambiguously worded law that allows the discussion of theories about the origin of life and the universe in science classes, which some see as an invitation to teach intelligent design. It hasn’t yet been tested in court.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

This week marks the 100th anniversary of the Scopes Monkey Trial, formally known as the State of Tennessee vs. John Thomas Scopes. Scopes was a teacher accused of breaking a Tennessee law that prohibited lessons on human evolution. And the entire nation was riveted. NPR’s Nell Greenfieldboyce reports on why this famous trial still resonates today.

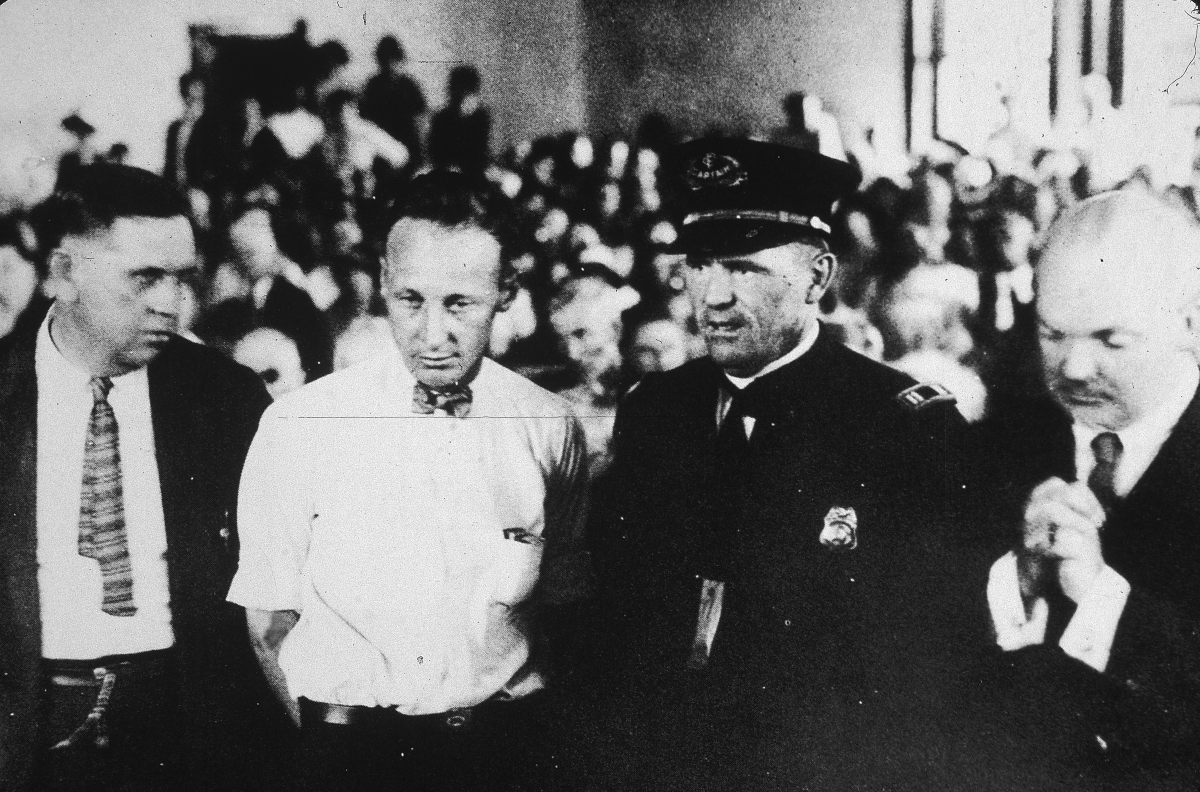

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE, BYLINE: The Scopes Trial was fictionalized in the play “Inherit The Wind,” which became a classic movie in 1960. It opens with somber town leaders, including a badge-wearing lawman, marching into a school.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “INHERIT THE WIND”)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) For our science lesson for today, we will continue our discussion of Darwin’s theory of the descent of man.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: There, in front of the students, the teacher was arrested.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “INHERIT THE WIND”)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) You’re charged with violation of Public Act 31428, volume 37, statute…

GREENFIELDBOYCE: The reality was nothing like that. The Scopes Trial was a completely contrived event dreamed up by civic leaders in Dayton, Tennessee, who were chatting at a drugstore soda fountain. They’d read in the newspaper that the American Civil Liberties Union was looking for a test case to challenge the new state law, and they figured, why not get our town some publicity? So the head of the school board sent for a 24-year-old substitute teacher, John Scopes, and asked him, will you let us use you for this?

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

JOHN SCOPES: And I said, well, OK.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: Scopes recalled that moment in an interview with radio legend Studs Terkel. In the archival tape, Scopes said within 30 minutes of his agreeing to the plan…

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

SCOPES: It was on the wires out of Chattanooga…

STUDS TERKEL: That you were arrested.

SCOPES: …That I was arrested.

TERKEL: But had you taught at the school?

SCOPES: Well, I had taught a class in biology for about three or four weeks.

EDWARD LARSON: Scopes had never taught evolution, and nobody thought he did.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: That’s Edward Larson, a historian with Pepperdine University. He says what was called a trial was really more of a staged public debate. Famed attorney Clarence Darrow volunteered to defend Scopes. The role of prosecutor went to the well-known populist William Jennings Bryan.

LARSON: You had two magnificent orators in Bryan and Darrow making their arguments, backed up by a legion of supporters, who are also articulate, on both sides.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: This was the first trial ever broadcast on radio. Thousands of newspapers followed the story. It’s become part of American folklore. Larson says a lot of people today think that Scopes won.

LARSON: (Laughter) That’s the biggest misconception.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: In fact, the jury deliberated for less than 10 minutes and found him guilty. Both sides claimed a moral victory, but Larson says if you read newspaper editorials from 1925, they mostly just marveled at how the country was divided and how it seemed like this divide would persist. To Ken Ham, this division is the inevitable result of fundamentally different world views. He’s the founder of Answers in Genesis, the Creation Museum and the Ark Encounter in Kentucky. He once debated evolution with science educator Bill Nye. Ham believes that creationism versus evolution is really about who we are, where we came from, the purpose and meaning of life.

KEN HAM: If there is a god who created us, and it is the God of the Bible, then he determines right and wrong and good and evil, and we have an absolute authority. But if you are just the result of natural processes, and there is no God, who determines right and wrong? Who determines good and evil?

GREENFIELDBOYCE: Many Americans, however, see no conflict between their religious beliefs and human evolution. Kenneth Miller is a biologist and a practicing Catholic who cowrote a widely used biology textbook. Its emphasis on evolution got it embroiled in a couple of court cases. He sees real progress in getting evolution taught and accepted.

KENNETH MILLER: After many years of the American public being 50/50 on evolution, we now have a substantial majority saying they accept evolution in terms of the evolution of the human species.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: Still, in a Pew Research Center survey released earlier this year, 17% of Americans said that they believed, quote, “humans have existed in their present form since the beginning of time.” And Miller says he continues to see efforts to stop or influence the teaching of human origins as well as other contentious science subjects like climate change and vaccines.

MILLER: Last year, West Virginia passed a law that allows the introduction of so-called alternative theories with respect to controversial topics in science classes.

GREENFIELDBOYCE: Some say this law was intended to open the door to classroom discussions of creationism, but unlike the law at the center of the Scopes Trial, Miller says it hasn’t been tested in court. Nell Greenfieldboyce, NPR News.

House Dem. Leader Jeffries responds to air strikes on Iran by U.S. and Israel

NPR's Emily Kwong speaks to House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY), who is still calling for a vote on a war powers resolution following a wave of U.S.- and Israel-led airstrikes on Iran.

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed in Israeli strike, ending 36-year iron rule

Khamenei, the Islamic Republic's second supreme leader, has been killed. He had held power since 1989, guiding Iran through difficult times — and overseeing the violent suppression of dissent.

Found: The 19th century silent film that first captured a robot attack

A newly rediscovered 1897 short by famed French filmmaker Georges Méliès is being hailed as the first-ever depiction of a robot in cinema.

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.