Alabama Bans Critical Race Theory In Schools

The Alabama State Board of Education officially banned critical race theory in the state’s 1,637 schools at its meeting on Thursday. The resolution’s official name is the “Preservation of Intellectual Freedom and Non-Discrimination in Alabama Public Schools.” But the policy essentially limits how educators can talk about race.

The vote was split across party and racial lines. All seven Republicans on the board, who are white, voted yes to ban critical race theory from being taught in Alabama public schools. The only two Democrats on the board, who are Black, opposed the ban.

None of the board members who voted in favor of the resolution shared their reasoning from the dais. However, Yvette Richardson, the board president pro tem, said she was concerned about what it means to “preserve intellectual freedoms” for teachers.

“All I ask is that we allow our teachers to teach history that is factual,” Richardson said. “As it stands now, our teachers have already for years taught about civil rights. They taught about slavery, and there’s never been a problem.”

Critical race theory is not taught in Alabama public schools and never has been. Still, with the vote, Alabama joins one of at least seven in the country to ban the concept, which has grown more controversial this year. It’s still unclear what ramifications educators or school districts may face if they violate the ban.

“It will have no impact on curriculums or any education standards,” Michael Sibley, the director of communications for the Alabama State Board of Education, told WBHM. “Alabama doesn’t teach CRT. The resolution basically says we still don’t teach CRT.”

In July, the board of education discussed the details of the resolution but did not come to a consensus on how to define critical race theory or what it might look like in the classroom.

Board members expressed concerns about students being labeled as “oppressors” or seeing themselves as victims, but they also acknowledged the importance of reckoning with Alabama’s history of racism.

Regardless, seven Alabama residents spoke against the ban before the vote at the meeting. One of the speakers was Birmingham City Schools board member Terri Michal, who is running for reelection this year.

“As white folks, we don’t often have to have those conversations. Black children are forced to grow up and face these issues of race before our white children. And I’m sorry, it is not the end of the world if our white children get uncomfortable at school,” Michal said.

Bernard Simelton, the president of the Alabama National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, also opposed the resolution.

“While the Alabama State Board of Education is busy passing vague resolutions, most of Alabama teachers are busy teaching facts and following Alabama state standards,” Simelton said. “This resolution, if passed, will sow distrust and erode confidence in our public schools and hardworking educators.”

The resolution states that it prohibits “offering K-12 instruction that indoctrinates students in social or political ideologies or theories that promote one race or sex above another” and that educators cannot teach students to “believe that one race or sex is inherently superior to another.”

Benson Miller, with Urban Conservatives of America, a political group, told the state board he supported the resolution and felt that critical race theory has no place in schools, even though it’s hard to define.

“Do you think that it’s right to judge people by the color of their skin?” Miller said. “That’s what critical race theory does, and it’s going to create — it already has — it creates resentment and division.”

Even if the ban doesn’t have any tangible effect on teaching or curriculums in Alabama, state board member Tonya Chestnut said it could still affect teachers even without clear enforcement.

“I’m also concerned that this resolution will put teachers in a position where they feel uncomfortable or even fearful to teach the truth,” Chestnut said.

Other concerns about the resolution are that it takes focus away from what’s really affecting schools right now: COVID-19.

“Alabama is in a crisis, but that crisis is not CRT,” Chestnut said. “We have a serious crisis relevant to the health and well-being of our student’s personnel as it relates to this pandemic.”

Kyra Miles is a Report for America Corps Member reporting on education for WBHM.

Voting nears to a close in Texas primary that may be crucial to control of the Senate

The GOP and Democratic primaries mark a potential litmus test for what direction base voters want their parties to go ahead of midterm elections this fall that will determine power in Congress.

Pregnant migrant girls are being sent to a Texas shelter flagged as medically risky

Government officials and advocates for the children worry the goal is to concentrate them in Texas, where abortion is banned.

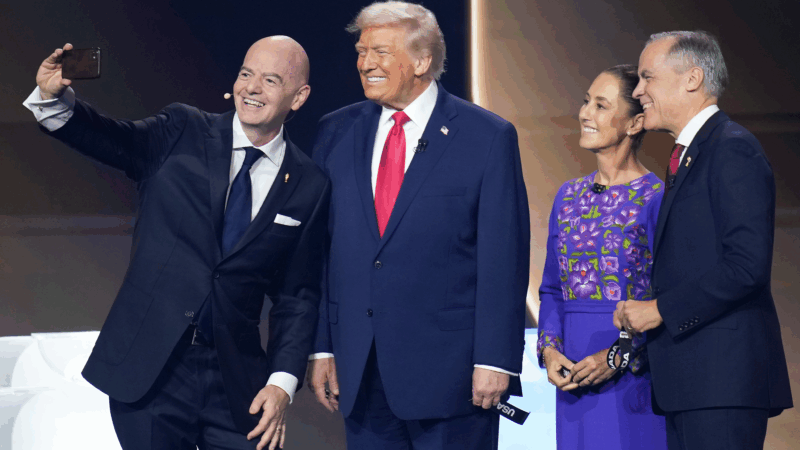

The 2026 World Cup faces big challenges with only 100 days to go

Will Iran compete? Will violence in Mexico flare up? And what about funding for host cities in the U.S.? With only 100 days left before it beings, the 2026 World Cup in North America is facing a lot of uncertainty.

A glimpse of Iran, through the eyes of its artists and journalists

Understanding one of the world's oldest civilizations can't be achieved through a single film or book. But recent works of literature, journalism, music and film by Iranians are a powerful starting point.

Mitski comes undone

She may be indie rock's queen of precisely rendered emotion, but on Mitski's latest album, Nothing's About to Happen to Me, warped perspectives, questionable motives and possible hauntings abound.

This quiet epic is the top-grossing Japanese live action film of all time

The Oscar-nominated Kokuho tells a compelling story about friendship, the weight of history and the torturous road to becoming a star in Japan's Kabuki theater.