Surviving A Pandemic: How The 1918 Spanish Flu Changed Life In Alabama

In 1918, Edna Register Boone and her family were living in the rural community of Madrid in south Alabama.

“I was 10 years old and my family was the only family in the little town that did not contact the flu,” Boone said. “Therefore my parents became automatic nurses.”

In a 2007 interview with the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH), Boone described her memories of living through the Spanish Influenza pandemic.

She said her family cared for the whole community. Her father planted a sweet potato patch and her mother prepared jars of soup. Boone would put on a gauze face mask and carry food to sick neighbors. Sickness, she said, was everywhere.

Widespread Death

The 1918 flu was especially deadly and spread quickly throughout the world in several phases. The first case of the illness in Alabama was reported in Huntsville in late September, 1918. Three weeks later, there were at least 25,000 cases in the state.

Annie Laurie Williams was just three years old at the time, living in Selma.

“I mean we were more or less confined to the house and should have been,” Williams said during a 2007 interview with the ADPH. “I don’t mean that it was a legal imposition, but I think we just did it almost voluntarily because … you didn’t want to get out.”

According to news reports from that time, Alabama closed public places like schools and churches in October. If people did go out, it was likely for medical help, but there was not much that could be done.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Members of the American Red Cross work ambulance duty during the influenza pandemic.

Boone said there was just one doctor in her small town, and he was overwhelmed. The nearest hospital was at least 15 miles away in Dothan.

“If you loaded a sick person and put him in a wagon and take him to a hospital, chances are that patient would be dead when they got there,” Boone said. “Ok if he wasn’t, there would be no room. The rooms would be filled. The doctors would be worked to capacity. That’s why most families just buried their own dead.”

Boone said there were no church burials. She recalled entire families dying from the virus.

It is not known exactly how many people died during the 1918 pandemic. Estimates are at least 50 million worldwide, with almost 700,000 deaths in the U.S. And this was during a time when the population was much smaller than it is today.

A Different Time

There are several key differences between then and now, according to Steven Austad, professor and chair of the biology department at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“1918 was still a phase of medicine where doctors were probably killing more people than they were saving, so … really they didn’t have a clue as to what to do,” Austad says.

U.S. National Archives

U.S. soldiers gargle with salt and water as “prevention” against influenza.

Medicine and technology have advanced a lot in 100 years. Today, there may not be a vaccine or a cure for COVID-19, but scientists are working quickly to get there. And Austad says in general, people know a lot more about how viruses work.

He says another important thing to remember about the 1918 pandemic was that the flu struck during World War I.

“Exactly about the time that the war ended was when it was at its height,” he says, “and now you have all these people going back to their home countries and really spreading it in just, in dramatic fashion.”

The virus overtook U.S. army camps, where thousands of men lived close together with limited access to hygiene.

U.S. National Archives

The 39th Regiment of the U.S. Army marches through the streets of Seattle wearing masks. The soldiers were on their way to France.

Austad says because countries were at war, they also censored information. They did not want to put their troops at a disadvantage or cause panic about a deadly illness. This delayed any efforts to slow the spread of the flu.

Today, Austad says there have been political disagreements about the coronavirus response, but information moves much faster than it did in 1918.

Fear and Uncertainty

Despite the differences, there are some common experiences of living through a pandemic. There is fear and uncertainty. And people adapt.

In the community of Madrid, Edna Boone said neighbors helped one another and they shared in their grief.

“It brought families closer together and it brought our little town closer together,” Boone said. “Because we all suffered losses, one way or the other, if not through war, then through the epidemic.”

U.S. National Archives

Red Cross workers make “anti-influenza masks” for soldiers.

When Boone was interviewed in 2007, she was asked about the possibility of another pandemic.

“Oh my goodness, what if it happened, suddenly, say even three or four days, or some sort of epidemic sweep through,” she said. “I think the only thing I could suggest about that is to be aware that it could happen again.”

Annie Laurie Williams also offered a few words of advice.

“Go to your doctor, get your medicine, go home, be sure you’ve got plenty of food, and stay there,” she said.

Both Williams and Boone have since passed away. Williams died a few years ago at the age of 98. Edna Register Boone passed away in 2011 at the age of 104.

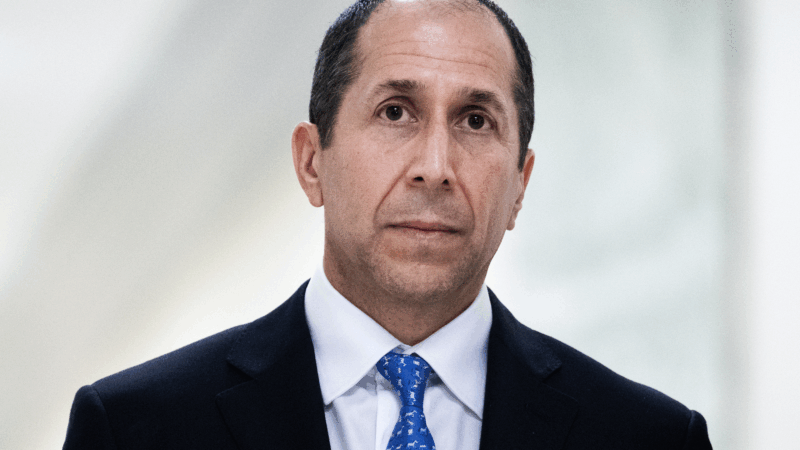

Epstein’s longtime accountant testifies he was ‘not aware’ of sex offender’s crimes

Richard Kahn testified to the House Oversight Committee that he did not know about Epstein's crimes. He said monetary gifts that Epstein made did not raise any red flags.

Rebecca Gayheart Dane on caring for her late husband, Eric Dane, and synthetic voices

The wife of 'Grey's Anatomy' actor Eric Dane says caring for him gave her an "extra dose" of compassion for others.

Chile turns right: Kast inaugurated as nation’s most conservative leader since Pinochet

Chile has sworn in its most right-wing president in decades — and his rise, and ideology, are rooted in a small town beneath the Andes.

Iran’s soccer team cannot participate in the FIFA World Cup, Iranian minister says

Iran is set to play three games in the U.S. this June. But amid the U.S.-Israel military campaign that has killed Iran's supreme leader, Iran's sports minister said the team would pull out.

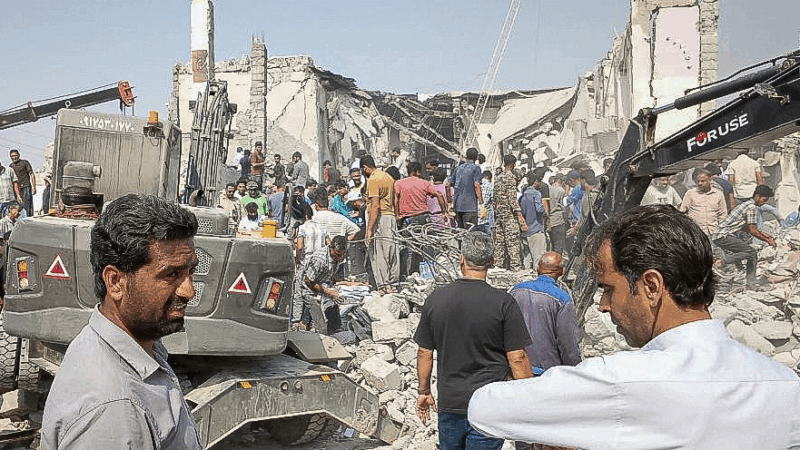

Pentagon probe points to U.S. missile hitting Iranian school

A military assessment suggests a U.S. Tomahawk cruise missile was responsible for at least 165 deaths at an Iranian girls' school, according to a U.S. official who was not authorized to speak publicly.

Harrison Ford isn’t retiring: ‘I really wouldn’t know what to do with myself’

Ford struggled to find his footing in Hollywood before being cast as Han Solo in Star Wars. Now 83, he plays a therapist in the Apple TV series Shrinking: "I really do love the work," he says.